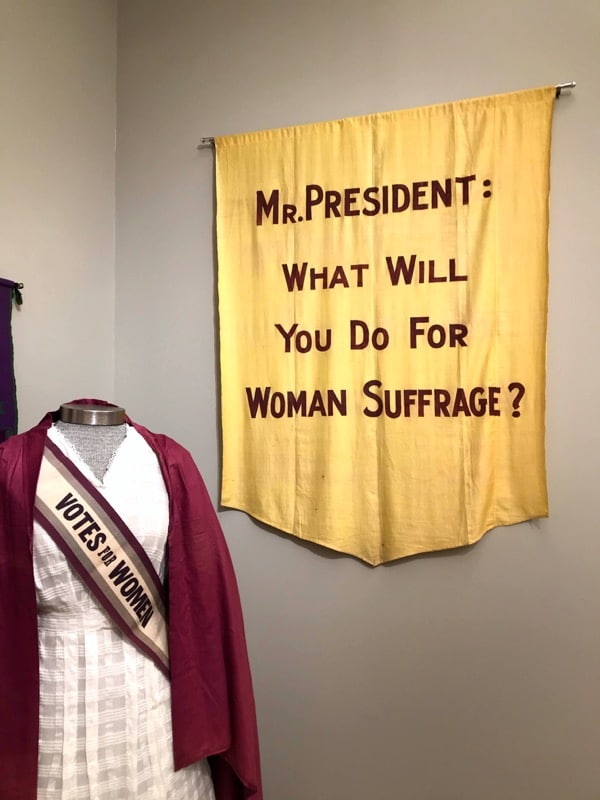

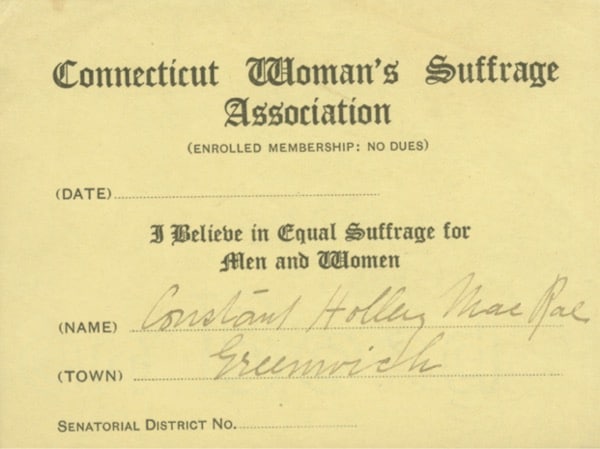

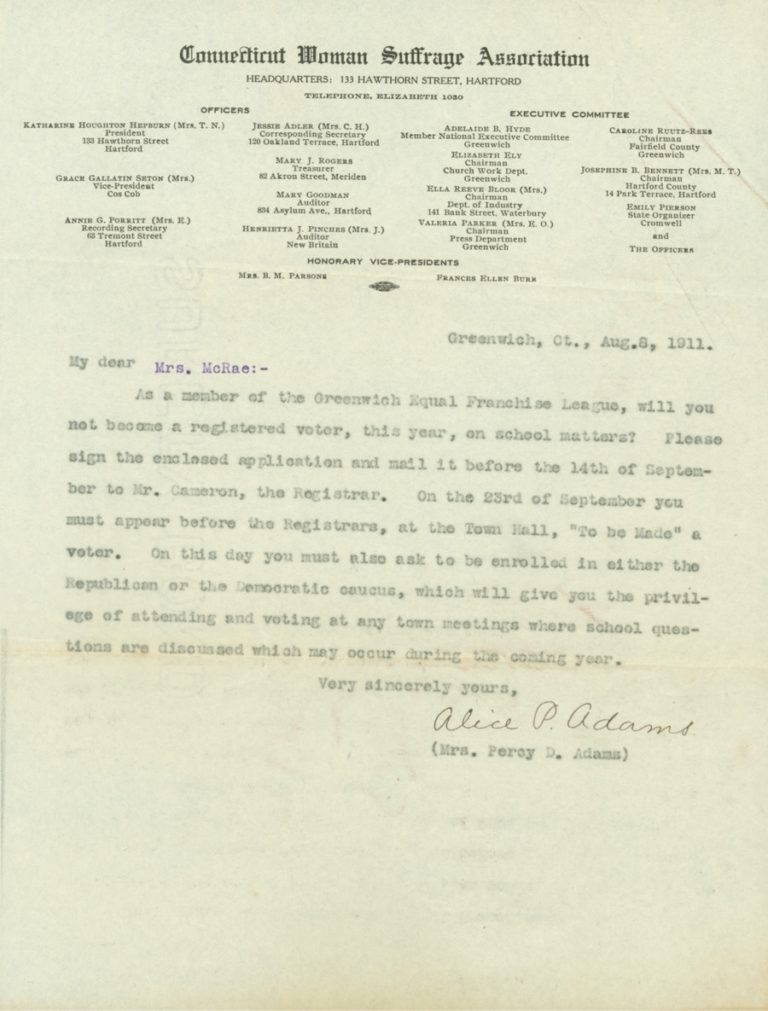

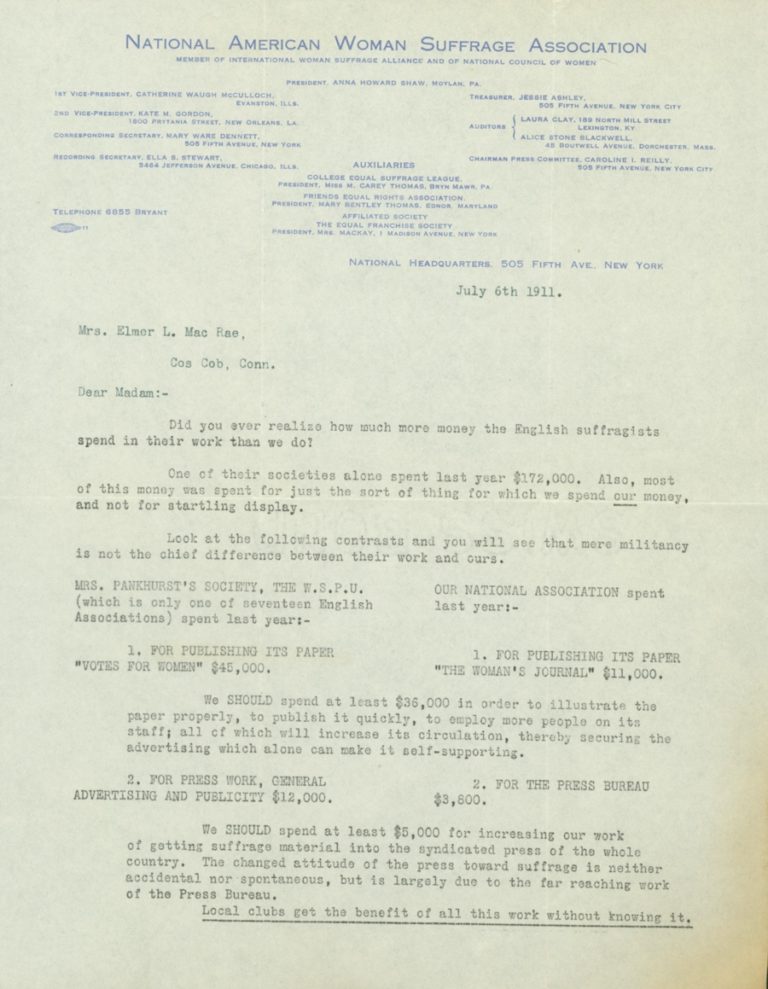

An Unfinished Revolution is on view at the Greenwich Historical Society February 5-November 1, 2020.

Curated by Kathleen Craughwell-Varda.

Exhibition Design by Whirlwind Creative.

The exhibition and this website are supported in part by a grant from Connecticut Humanities. The exhibition was generously supported by Northern Trust and the PepsiCo Foundation.