Early Women Activists

Before the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 kicked off the Women’s Rights Movement in the United States, many socially-minded American women found their voice as part of the growing call to abolish slavery. Women like Angelina and Sarah Grimké, daughters of a South Carolina slave owner, made public speaking tours to share their firsthand experiences with New England audiences. Abolitionist Lucy Stone of Massachusetts perfected her lecturing style from her brother’s church pulpit. These women also promoted equal rights in their speeches. As Stone said when criticized for calling for women’s rights, “I was a woman before I was an abolitionist.”

Abolitionists in Greenwich

Several churches in Greenwich showed support for emancipation, including the Second Congregational Church. Abolitionist preachers, such as Rev. Lyman Beecher, father of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Isabella Beecher Hooker, were invited to speak to the congregation.

Slavery in Greenwich

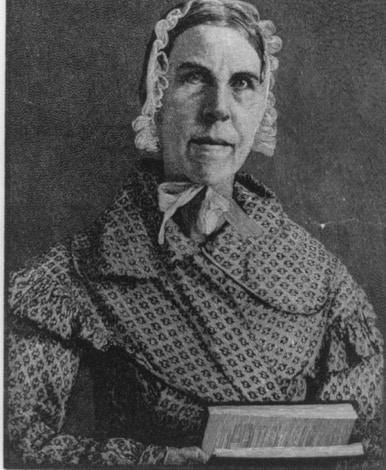

This unsigned watercolor painting of the Jabez Mead House is believed to have been painted by Hester Mead, an enslaved woman who was the daughter of Candice Bush, one of at least fifteen enslaved Black individuals enslaved by the Bush family of Cos Cob. Hester was born January 10, 1807, and freed in 1828 when she reached the age of 21. Her mother Candice was manumitted by Fanny Bush on January 3, 1825 at the age of 45.

Hester was indentured by the Bush family to a member of the Mead family of Greenwich. In the 1850 census she was listed as “Ester Mead, age 42.”

The Jabez Mead house was built in c. 1840 at the intersection of what is now East Putnam Avenue and Indian Field Road. It was torn down in 1939.

Learn more about Hester Mead, an enslaved woman in Greenwich

Born January 10th, 1807, Hester Mead was the last of eight enslaved children born in the Bush household, now the Bush-Holley House Museum. Hester’s mother was Candice Bush, who had been enslaved by the Bushes since she was a child. Her father is unknown.

As a young girl Hester was indentured to a member of the Mead family. Under this arrangement Hester worked at the Mead household while the Bushes, her enslavers, were paid for her labor. She spent most of her childhood away from her mother and brother, who remained at the Bush household. It is likely during this time that Hester took the last name Mead as her own.

Connecticut’s Gradual Abolition Act of 1784 dictated that Hester be freed upon her 21st birthday in 1828. Her mother Candice had been freed the year before, at the age of 45, and her brother Jack had been freed three years prior. While Jack’s whereabouts after being granted his freedom are unknown, Hester and her mother Candice lived together in freedom. They are listed together in the 1850 census along with Hester’s son, William Mead. By 1860 William had established a household of his own, with a wife and two daughters. Candice passed away in 1859 and was buried in Greenwich’s Union Cemetery.

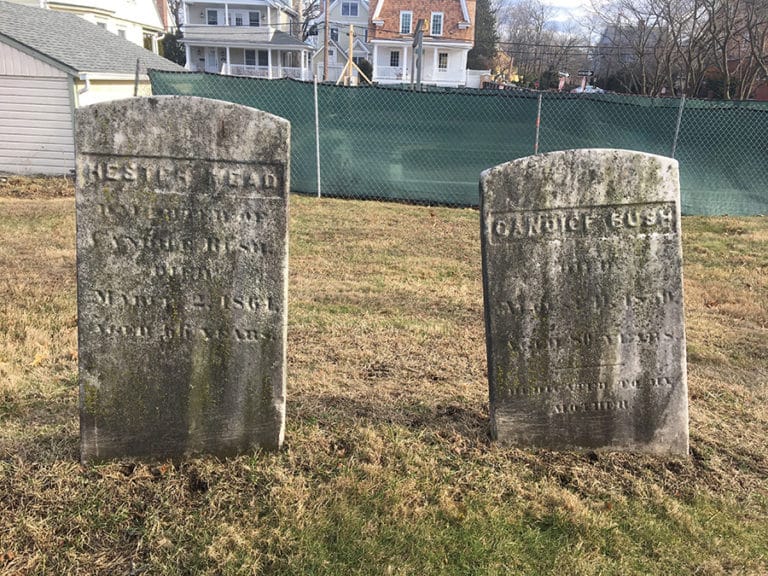

Candice Bush (1779?-1859)

Union Cemetery, Greenwich

After her mother’s death Hester moved to the household of Darius Mead, where she stayed until her own death in 1864. In her will Hester asked that her son William—who was serving in the Civil War—be brought to her funeral, for her possessions to be divided between her granddaughters, and for a headstone to be placed on both her and her mother’s graves.

Hester and Candice are the only formerly enslaved people in Greenwich to have graves marked with headstones. Burial markers were beyond the economic reach of most of Greenwich’s free Black community. These simple monuments stand as a testament to Hester’s ability to make her way in a world that was systematically stacked against her.

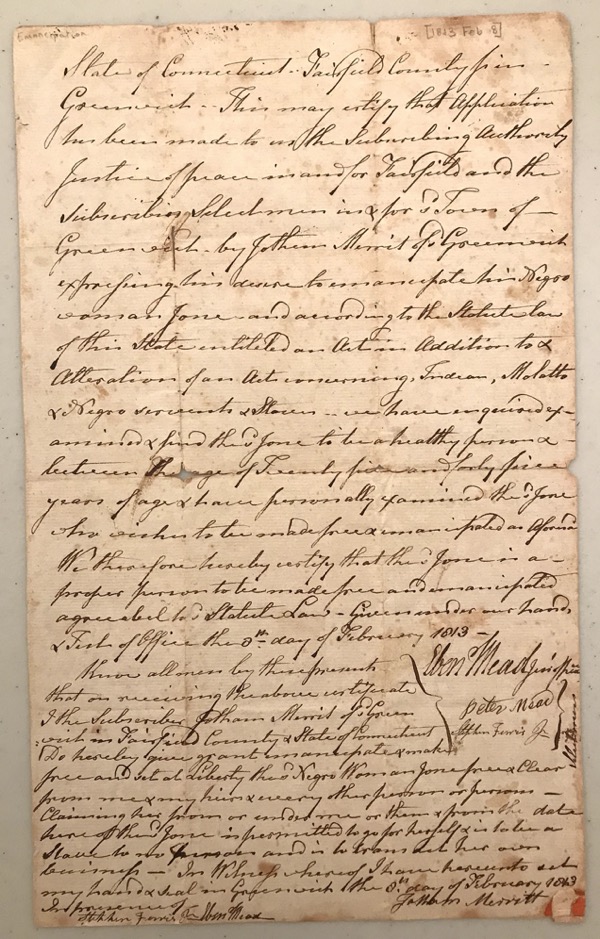

Manumission Document

This emancipation document provides a record of permission granted to Greenwich resident Jothan Merritt to grant freedom to an enslaved woman named Jane, in 1813. As reported in the document, the selectmen of Greenwich had examined Jane and determined she met the requirements for emancipation.

Early Suffragists

The right to vote was not the initial focus of early American feminists. These women sought more comprehensive equal rights. However, in the decade following the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention the push for suffrage gained momentum as Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone traveled the country delivering speeches, often written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

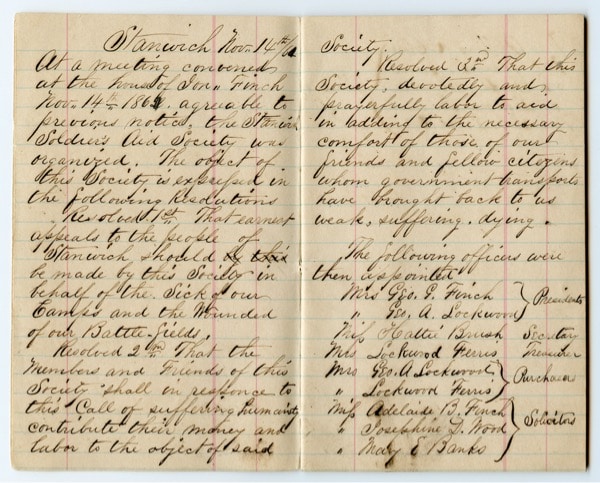

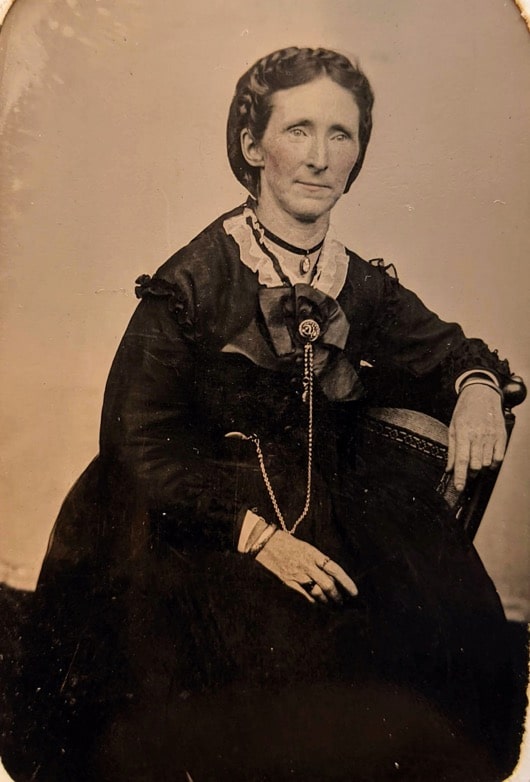

During the Civil War many American women supported troops on a local level by forming Soldier’s Aid Societies. In Greenwich, Mary Angeline Brush Lockwood and her sister Harrier founded the Stanwich Soldier’s Aid Society. As a local branch of the national United States Sanitary Commission, the Stanwich Soldier’s Aid Society was charged with helping sick and wounded soldiers by soliciting donations from the people of Stanwich, a village in Greenwich, and contributing the members’ own time and money for the soldiers’ benefit.

After the Civil War many American women expected to be rewarded for their work as abolitionists and organizers with the right to vote. The passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868, addressing citizenship rights and equal protection of the law, and the 15th Amendment in 1870, giving African American men voting rights, frustrated many white women who felt they had been overlooked. Fractures and dissention among women’s rights activists led to a weakened suffrage movement through the rest of the 19th century.

Tintype with hand coloration

Greenwich Historical Society, Brush-Lockwood Papers

Stanwich Soldier’s Aid Society

The women of the Stanwich area of Greenwich supported soldiers during the Civil War through the Soldier’s Aid Society. The success of their efforts, and of women throughout the North who organized similar societies, made many women more conscious of their ability to collectively effect important social change.

Isabella Beecher Hooker and the CWSA

In 1868 the New England Woman Suffrage Association was founded. The following year the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association was formed. Isabella Beecher Hooker was a founding member of both organizations. Half-sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe and a resident of Hartford, she was a lecturer and activist who led the Connecticut women’s suffrage movement for 36 years.

In this photograph depicting the abolitionist Lyman Beecher and his wife and children, Isabella Beecher Hooker is seated on the far left of the front row and her sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, is on the far right.

Courtesy of the Helga J. Ingraham Memorial Library, Litchfield Historical Society

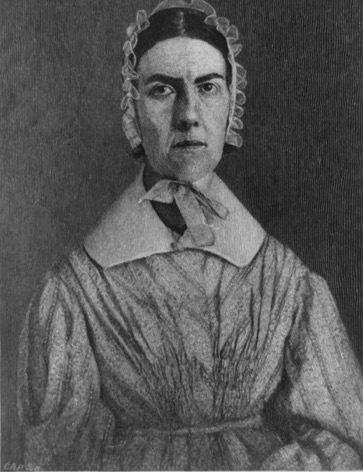

Lucy Stone to Isabella Beecher Hooker

As an early suffragist leader in Connecticut, Isabella Beecher Hooker regularly corresponded with other leading activists of the suffrage movement. In letters Hooker received from Susan B. Anthony in 1878 and Lucy Stone in 1869, the women debate their stance on the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Lucy Stone wrote to Hooker: “I believe that just so far as we withhold or deny a human right to any human being, we establish a basis for the denial and withholding of our own rights.”

Letter, Lucy Stone to Isabella Beecher Hooker, August 4, 1869

Courtesy of Rare Books & Special Collections, Rush Rhees Library, University of Rochester