Marketing Suffrage to America

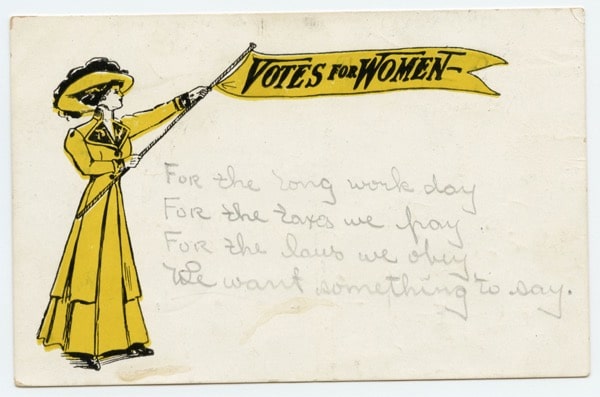

In the mid-19th century the women’s suffrage movement was considered radical. By the turn of the 20th century, as the Progressive Movement took hold in American politics more women and men supported women’s suffrage.

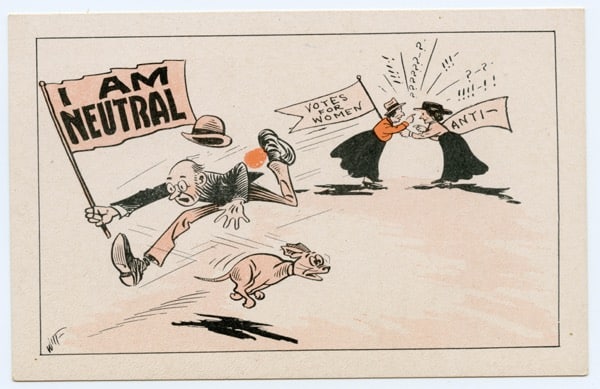

There were still groups opposed to suffrage that worked to prevent passage of the 19th Amendment. Among these were the “Antis” ‒ women opposed to suffrage. They argued that women were not well suited for politics. In an effort to combat negative stereotypes, the suffrage movement produced marketing materials that reframed the movement and the women who supported suffrage. Postcards, buttons, badges, fans and other items allowed women to proudly show their support and participation in the movement to gain the vote.

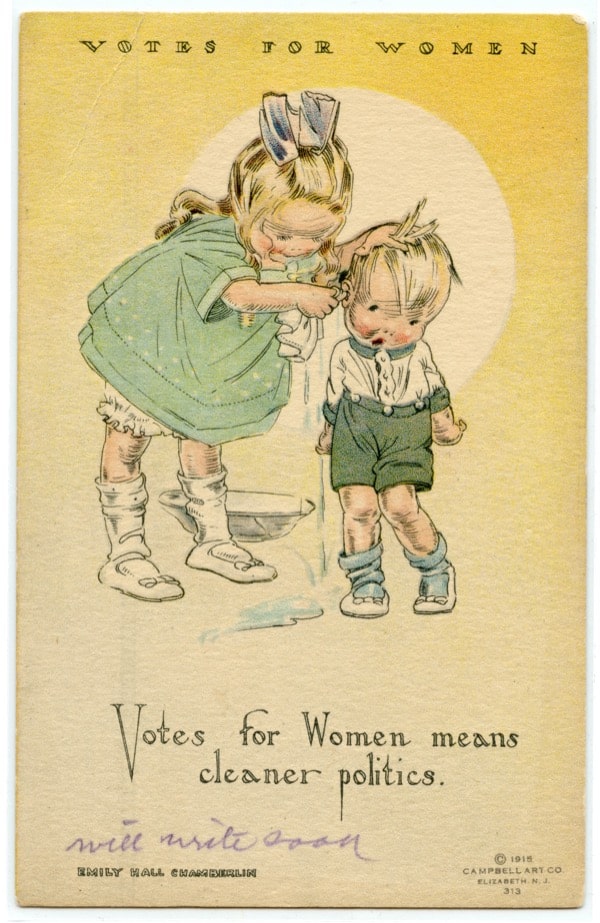

This card promotes a common theme among suffrage activists — that politics would be less corrupt if women were allowed to vote.

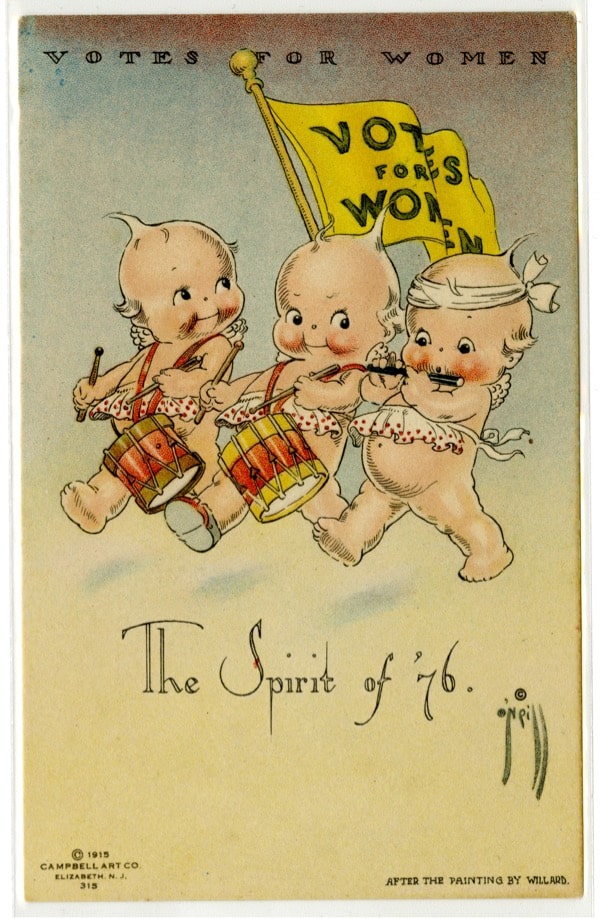

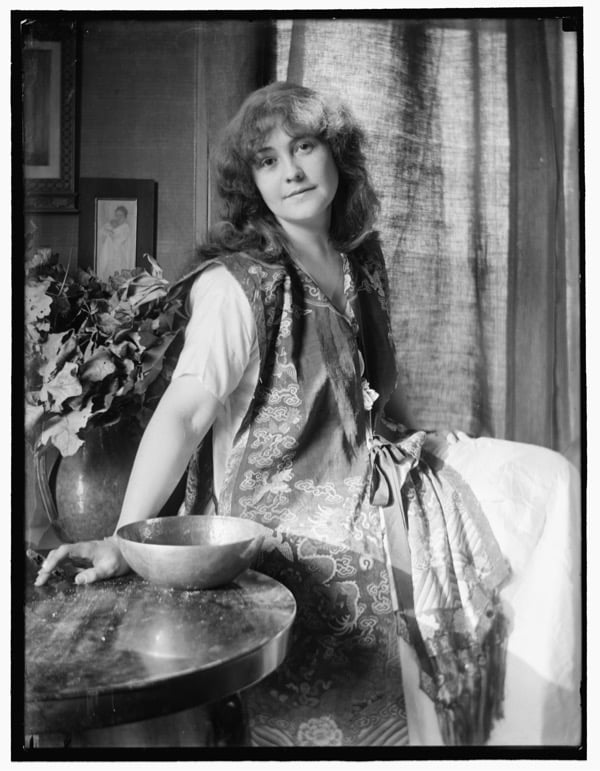

The Suffragist “Kewpie”

Rose O’Neill (1874-1944) a resident of Westport, Connecticut, was an illustrator most famous for invented the “Kewpie” figure, the most popular cartoon character before Mickey Mouse. She was also a suffragist who produced illustrations for the suffrage movement featuring her Kewpie character. O’Neill was a frequent visitor to the Holley boarding house to socialize among the lively artists of the Cos Cob art colony.

Library of Congress

The Hartford Suffrage Parade of 1914

In March 1913 Alice Paul and the National American Woman Suffrage Association organized the first suffrage parade, held in Washington, D.C. The event drew attention to the suffrage movement and galvanized women around the country. Following this success, suffrage leaders called for a National Day of Suffrage on May 2, 1914.

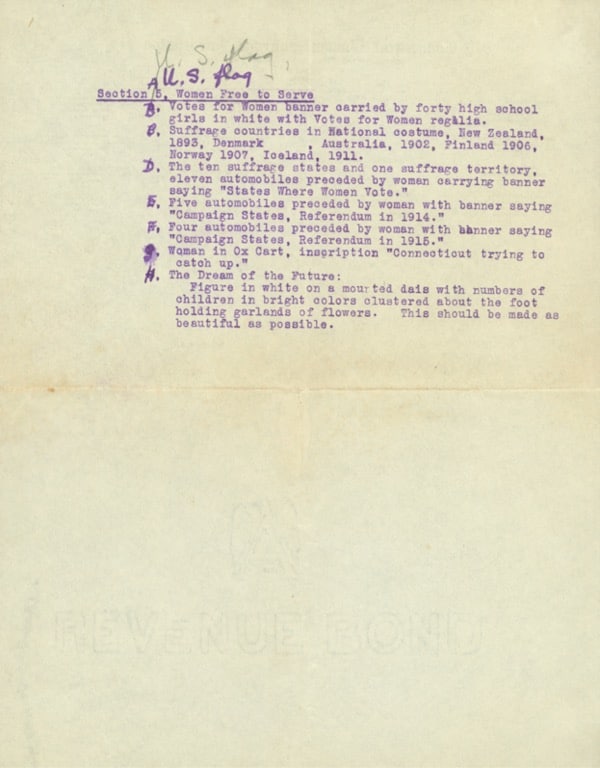

To mark the event the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) planned a march through Hartford. In preparation for the parade, Emily Pierson of the CWSA executive committee asked Greenwich’s Grace Gallatin Seton to oversee the design and planning of the parade floats and costumes. Suffrage leagues from Hartford, Bridgeport, Greenwich, Ridgefield, New Canaan, Westport and Salisbury supplied floats. The Greenwich Equal Franchise League provided two floats, one illustrating women being admitted to college and another featuring Mary Lyon, a pioneer in women’s education.

The Suffrage Parade began in front of the State Capitol Building and then passed under the Soldiers and Sailors Monument to downtown Hartford.

To illustrate how women worked in a wide variety of professions, the parade marchers were divided into categories. Several Greenwich women served as parade marshals: Dr. Valeria Parker led the female physicians, Mary F. Robinson led the female photographers and Elsie Tiemann was at the head of the female municipal officers.

Thousands of people lined the streets of Hartford to see the 2,000 participants march. The parade had its desired effect; it provided exposure for the suffrage movement and drew more women and men to the cause. A film of the parade was shown in theaters across Connecticut and declared “a hit” by The Naugatuck Daily News.

Suffrage Stories: The Color White

Hear exhibition curator Kathy Craughwell-Varda explore the symbolism of the color white, which for decades has been worn in solidarity in support of women’s rights.

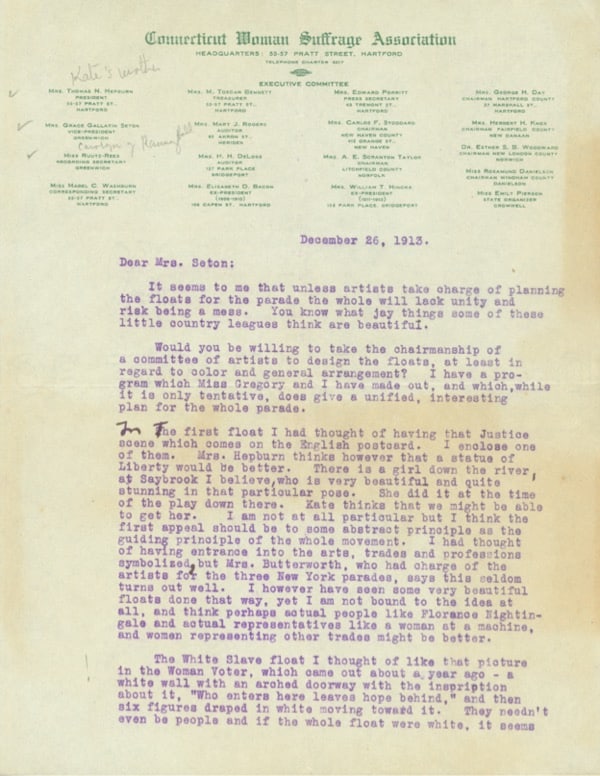

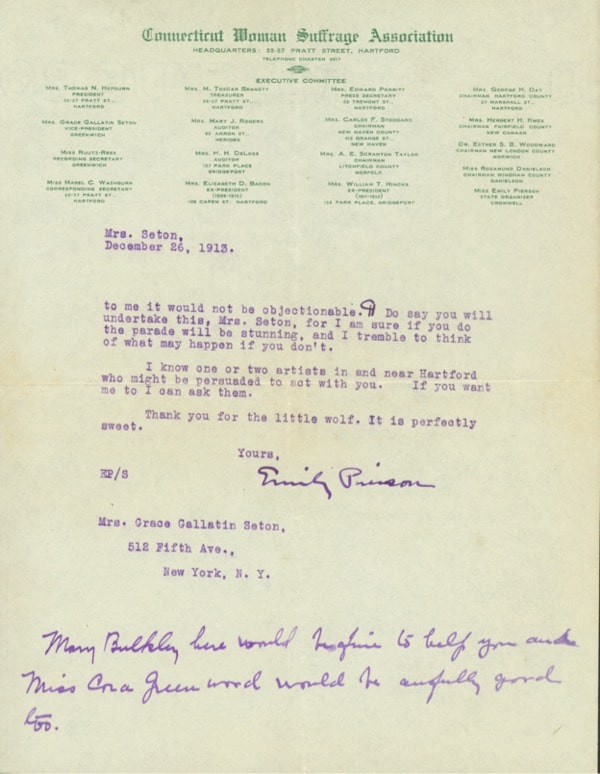

“Do say you will undertake this, Mrs. Seton…”

In this letter, CWSA executive committee member Emily Pierson makes an appeal to Grace Gallatin Seton of Greenwich to lend her artistic talents to the design and organization of the Hartford suffrage parade. Seton agreed, and chaired a committee of artists who designed parade floats.

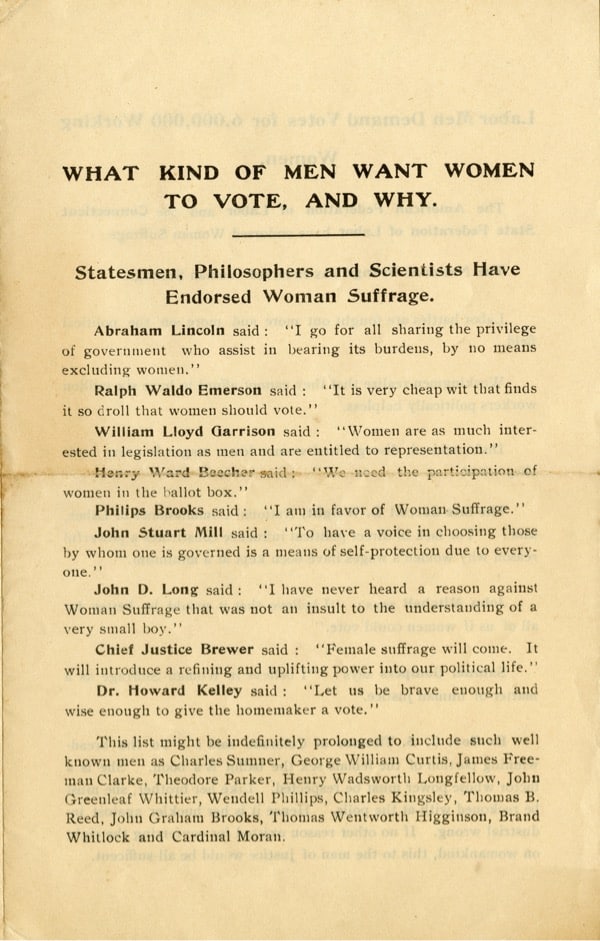

Men and the Suffrage Movement

The fight for the right to vote challenged deeply rooted gender roles. Victorian America saw a woman’s proper role as wife and mother. However, by the end of the 19th century, there were more women attending college and entering non-traditional professions. The women who embraced the suffrage movement were portrayed by opponents of the cause as mannish, unattractive and single. The original Old Maid in the card game was a suffragist.

The men who supported suffragists were looked down on for surrendering their superiority to women and were depicted as being henpecked. To win over men to their cause, suffrage leaders realized they needed to rewrite the narrative and create marketing materials that presented the suffragist as a confident and attractive woman, less threatening to men.

Men had been part of the women’s suffrage movement since Seneca Falls, where 32 men, including escaped slave Frederick Douglass, signed the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments. The husbands of many of the first generation of suffragists supported their wives and were committed to the cause of female enfranchisement. However, these men were in the minority in 19th-century America. In the early 1900s, the suffrage movement gained the support of prominent men, including Theodore Roosevelt, whose advocacy led more men to the movement. It may have taken 72 years, but in the end, the suffragists successfully convinced men to support and ratify the 19th Amendment.

Greenwich Historical Society, Holley-MacRae Papers

Elmer Livingston MacRae supported women’s suffrage, donating one of his paintings to the cause and maintaining membership with the CWSA and GEFL.

“Would Female Suffrage Increase or Diminish Crime?

William Thompson Dewart was the publisher of The New York Sun with residences in New York City and Greenwich. In this opinion piece he shared his thoughts regarding women’s suffrage: “There are no doubt a great many wise and good women, but they are in the minority, and would not be the ones who would lead the sex in case female suffrage were granted.”

William Thompson Dewart

“Would Female Suffrage Increase or Diminish Crime?,” ca. 1902

Greenwich Historical Society, Dewart Papers

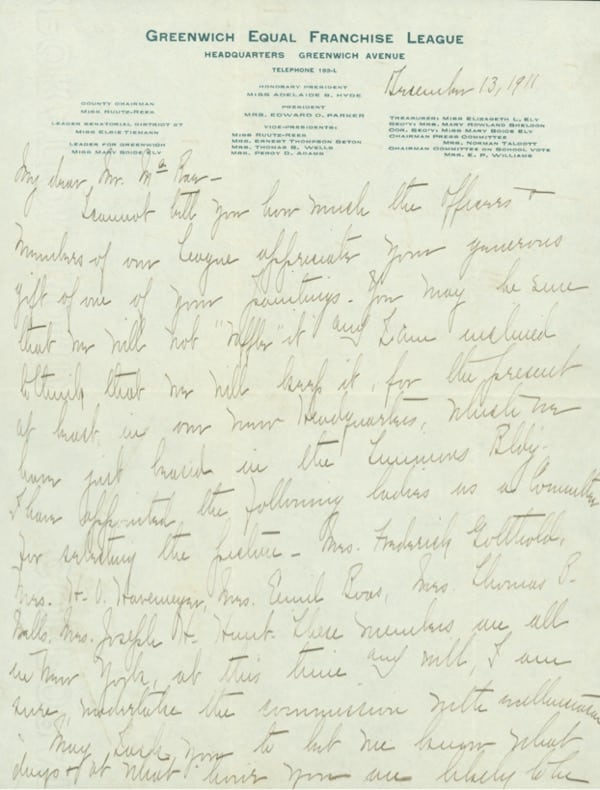

“My Dear Mr. MacRae…”

Dr. Valeria Parker of the Greenwich Equal Franchise League (GEFL) wrote to thank MacRae for his donation of a painting. She also informs him that a group of women from GEFL, including Louisine Havemeyer, will be coming to select the painting. The painting selected is not known.