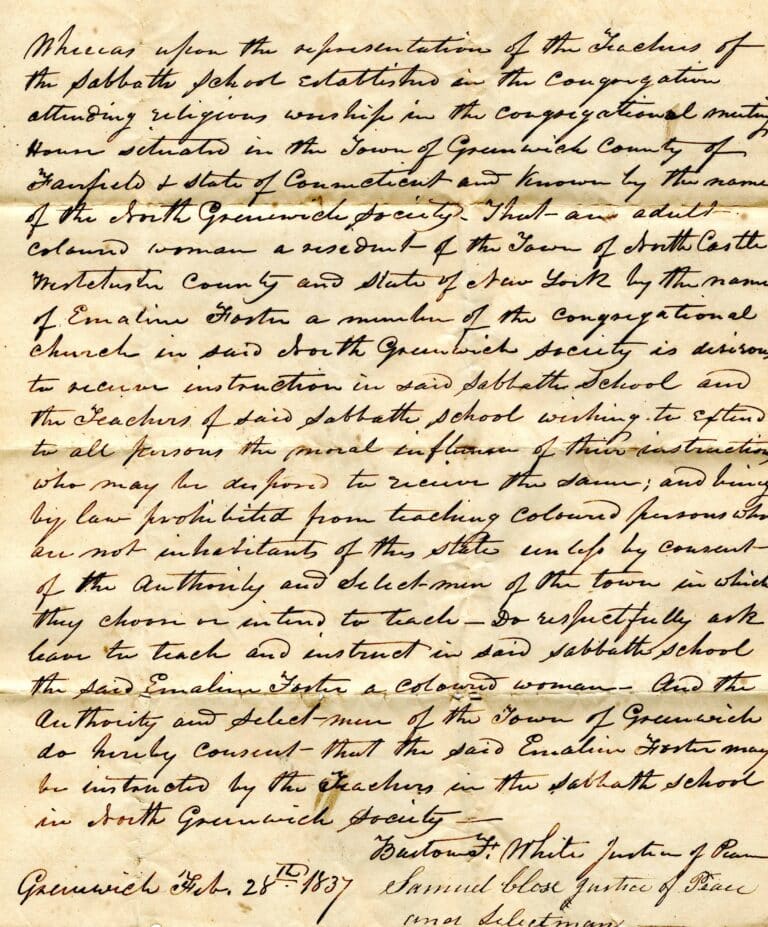

On February 28th, 1837, the Selectmen of the Town of Greenwich gave permission for the teachers of the North Greenwich Congregational Church Sabbath School to educate a woman named Emaline Foster. The letter shown bellow, granting Ms. Foster permission to attend the church’s school, highlights a brief but important moment in the history of civil rights.

Emaline Foster was a Black woman who lived just north of Greenwich in North Castle, New York. She was a member of the North Greenwich Congregational Church, and was interested in attending their Sabbath School. However, she could not do so without the explicit permission of the town. This was not solely because of her race; public schools in Connecticut were integrated, at least on paper. And it was not solely because of her address; educational opportunities for those living out of state did exist in Connecticut at the time. Rather, it was due to the combination of her race and address that permission had to be sought.

The ‘why’ behind this letter can be found four years before. In 1833, Prudence Crandall opened a boarding school for Black girls in Canterbury CT, much to the chagrin of her neighbors. Her original intention had been to run a boarding school for white children, and her neighbors felt betrayed by the sudden change of direction and worried that the establishment of this school would lead to an influx of Black students from other states, with less educational opportunities, to their town. They asked Ms. Crandall to close her school, and when she refused, her neighbors took her to court.

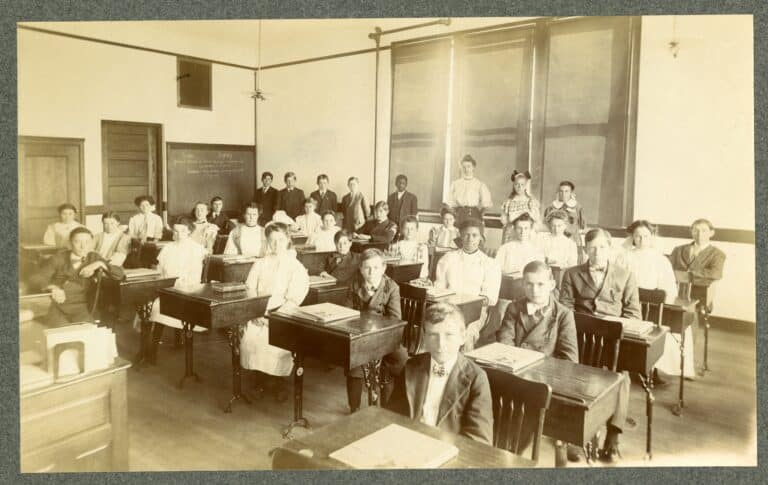

At the time, the people of Connecticut took pride in their integrated schools. They saw it as an expression of their superior abolitionist tendencies. This said, they did not relish the idea of Black families moving to Connecticut in mass to receive this education, both for the social and financial reasons. Thus, on May 24, 1833, the Connecticut legislature passed a “Black Law”, which prohibited schools from teaching African-American students from outside the state without the town’s explicit permission. The town of Canterbury was quick to refuse Ms. Crandall’s school, but she taught regardless. This led to her arrest.

Crandall’s arrest galvanized sections of the abolitionist movement, who fundraised to help fight her case. In court, the defense argued that Ms. Crandall’s arrest should be repealed as the law that made it possible was fundamentally unconstitutional. They argued that free Black people were considered citizens in other states and this status, and the rights that it gave, should not be lost when they entered Connecticut. Crandall’s lawyer, William W. Ellsworth stated “A distinction founded in color, in fundamental rights, is novel, inconvenient, and impracticable. Hitherto we have seen no such distinction… …These pupils are human beings, born in these states, and owe the same obligation to the state and the state’s governments, as white citizens.” The opposition argued that even though the Constitution did indeed say that “The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States” this did not matter, as free Black people were not citizens.

The Connecticut justice system, caught between the two sides and unwilling to take either, found an excuse to dismiss the case entirely, leaving the argument unresolved. Not long after, Crandall’s school was attacked. She was forced to both close the school and leave state for her safety and the safety of her students.

This is how it came to be that in 1837, Emaline Foster and the teachers who wished to help her, had to petition the Board of Selectmen of Greenwich for permission for her to attend their school. Being a Black woman who lived out of state, the laws brought into being during the Crandall case applied directly to her. Thankfully for Foster, the town of Greenwich approved the request and allowed her to attend the church’s school. Interestingly, one year later this permission would have been unnecessary. In 1838, the “Black Code” regulating school enrollment for out of state Black students was removed from the books.

The laws behind this letter concerning Emaline Foster only existed for five years, but their impact was significant. The questions of citizenship and the right to an education argued over in Crandall vs the State of Connecticut would be referenced time and time again in court. The influence of this case can be traced most significantly to decisions such as Dred Scott vs Sandford in 1857, which declared that free Black people were not citizens (later overruled by the creation of the 13th and 14th amendments), and Brown vs Board of Education in 1954, which ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional.

There was also the personal toll of these laws. Ms. Foster, Ms. Crandall’s students, and so many like them, must have felt their futures in the balance with these rulings. While here in Greenwich, Emaline Foster was granted her right to an education, there were doubtless many others who were denied. Lives were forever changed by this law and the Selectmen who enforced it.

We do not know what happened to Emaline Foster after this letter was written. No doubt she happily received her education, but her life beyond this moment, and what she did with that education, remains a mystery. If you happen to know anything about Ms. Foster, please contact hlodge@greenwichhistory.org or cshields@greenwichhistory.org. The records, most likely, are out there, just waiting to be found.