Through research, education, and civic engagement, the WITNESS STONES PROJECT, Inc. seeks to restore the history and to honor the humanity and contributions of the enslaved individuals who helped build our communities.

Witness Stones Placement

Since 2019 the Greenwich Historical Society has collaborated with The Witness Stones Project on this initiative that seeks to teach school-age children about enslaved persons in their hometowns. Students from Sacred Heart Greenwich and Greenwich Academy have researched the lives of Cull Bush Sr., Patience, their children, Phillis, Milley, Rose, and Cull Bush Jr., Candice Bush, her son Jack, and daughter Hester Mead, and Charles. Together, we are bearing witness to the lives of these enslaved individuals who lived, worked and loved in this historic home.

According to Historical Society research, approximately 300 enslaved people resided in Greenwich. Altogether, about 15 enslaved people worked at the Bush-Holley House. All lived and worked for David Bush and family at the Bush-Holley House. “Witness Stone Memorials” cast from cement and bronze with engravings of each person’s name, known birth and death dates and primary occupations, are placed in a garden below an attic believed to be where most of the enslaved people lived.

Students and teachers from Sacred Heart Greenwich and Greenwich Academy worked in conjunction with the Historical Society in researching the daily lives of the enslaved. The annual ceremony is the culmination of their work over many months.

As of 2024, 15 memorial Witness Stones have been placed.

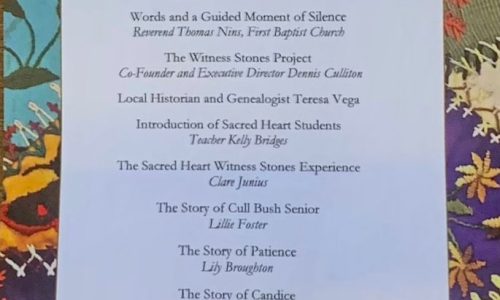

May 27, 2021 Ceremony

The May 27, 2021 ceremony honored four individuals — Cull Bush and his partner Patience, and Candice Bush and her daughter Hester Mead. Dennis Culliton, founder and executive director of The Witness Stones Project, and Teresa Vega, historian and genealogist gave opening remarks. Teachers Kelly Bridges and Angela Carstensen, from Sacred Heart Greenwich, and Kristen Erickson and Bobby Walker, from Greenwich Academy, worked with their students to research the lives of Cull, Patience, Candice and Hester. Their hard work and research was presented in a set of speeches from student representatives of each class and read during the ceremony. After closing remarks those in attendance had the honor of witnessing the placement of the stones.

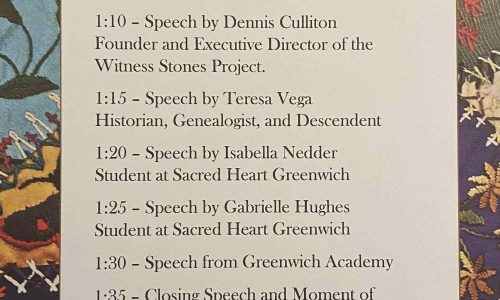

May 25, 2022 Ceremony

The May 25, 2022 ceremony honored Jack, eldest son of Candice and brother of Hester, and Cull Jr. youngest son of Cull Bush Sr., and Patience. Dennis Culliton, founder and executive director of The Witness Stones Project, and Teresa Vega, historian and genealogist gave opening remarks. Teachers Heather Coffey and Angela Carstensen, from Sacred Heart Greenwich, and Bobby Walker, from Greenwich Academy, worked with their students to research the lives of Cull Jr. and Jack. Their hard work and research was presented in a set of speeches from student representatives, Isabella Nedder and Gabrielle Hughes from Sacred Heart Greenwich, and read during the ceremony. Teacher Bobby Walker presented his student’s speech for Greenwich Academy. After closing remarks those in attendance had the honor of witnessing the placement of the stones.

May 24, 2023 Ceremony

The May 24, 2023 ceremony honored four individuals — Charles, and sisters, Phillis, Milley, and Rose. Dennis Culliton, founder and executive director of The Witness Stones Project, and Teresa Vega, historian and genealogist gave opening remarks. Teachers Heather Coffey, Jillian Wolf, and Chris Cunningham from Sacred Heart Greenwich, and Bobby Walker, from Greenwich Academy, worked with their students to research the lives of Phillis, Milley, Rose and Charles. Their hard work and research was presented in a set of speeches from student representatives read during the ceremony. After closing remarks, memorial Witness Stones were placed for the four alongside their friends and family who were honored in years before.

April 26, 2024 Ceremony

The April 26, 2024 ceremony honored four individuals — Lucy, Nanny, Peggy and Dorcas. Dennis Culliton, founder and executive director of The Witness Stones Project, and Teresa Vega, historian and genealogist gave opening remarks. Teachers Jack Sheehan from Sacred Heart Greenwich, and Bobby Walker, from Greenwich Academy, worked with their students to research the lives of Lucy, Nanny, Peggy and Dorcas. Their hard work and research was presented in a set of speeches from student representatives read during the ceremony. After closing remarks, memorial Witness Stones were placed for the four alongside their friends and family who were honored in years before.

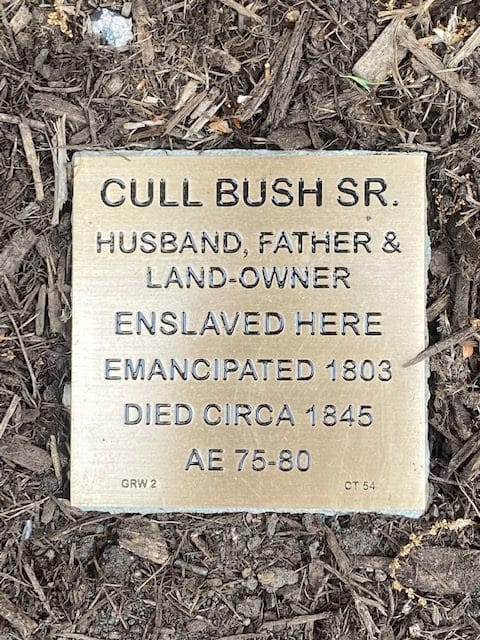

Cull Bush Sr.

Cull Bush Sr was one of the sixteen known enslaved persons held at the Bush-Holley House. Our earliest known record of Cull is in the first United States Census in 1790. We do not know when Cull was first enslaved at the Bush household, but we know he was held there until 1803, the year of his emancipation.

Cull spent half of his life enslaved, but that is only half of his story. Cull was also a father of six. He was a loyal partner to the mother of his children, Patience, who was also enslaved by the Bush family. After his emancipation, Cull worked hard to purchase land near his still-enslaved family in Cos Cob so he could continue to be part of their lives. Cull was an achiever. In a world systematically stacked against him, Cull created a family, a home, and a career.

Patience

Patience was one of the sixteen known enslaved persons held at the Bush-Holley House. Our first known record of Patience is a document recording the birth of her first child, Phillis. Over the next twelve years, Patience and her partner Cull, would have five more children together: Milley, Rose, Lucy, Nanny, and Cull Jr.

Thanks to the Gradual Emancipation Act, all of Patience’s children became free upon turning 21 years old. Her partner, Cull, was also freed not long after the birth of their youngest child. But Patience would never be free; she remained enslaved at the Bush household until her death circa 1830.

Patience can be remembered in the moments of strength born from love; the strength to bring six children into this world, the strength to help them grow in the hardest of situations, and the strength to see them go into the world, free, but without her.

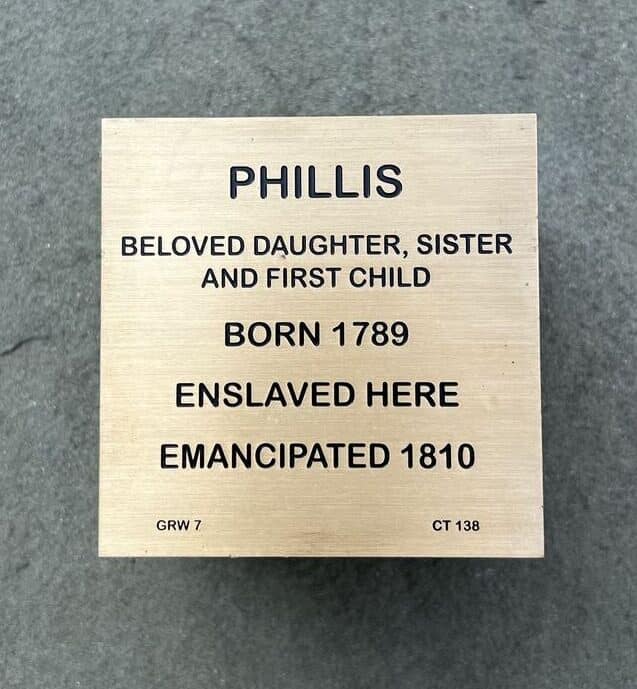

Phillis

Phillis was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. She was the oldest child of Cull Bush Sr and Patience, who were also enslaved by the Bush family. We know that Phillis lived in the Bush household with her family until the age of 9. We also know that she is no longer there by the age of 19. It seems that after the death of David Bush, the Bush family began to send Cull and Patience’s daughters out to serve in other households once they were old enough to work independently.

Phillis was willed to David’s Widow, Sarah, after his death, and would have served her, or had the money for her labor sent to Sarah, until she was legally freed on her 21st birthday by the Gradual Emancipation Acts. We do not currently know where Phillis lived and worked after she left the Bush household. No records of her in freedom have been found. If you have any information about Phillis, please contact Christopher Shields at cshields@greenwichhistory.org.

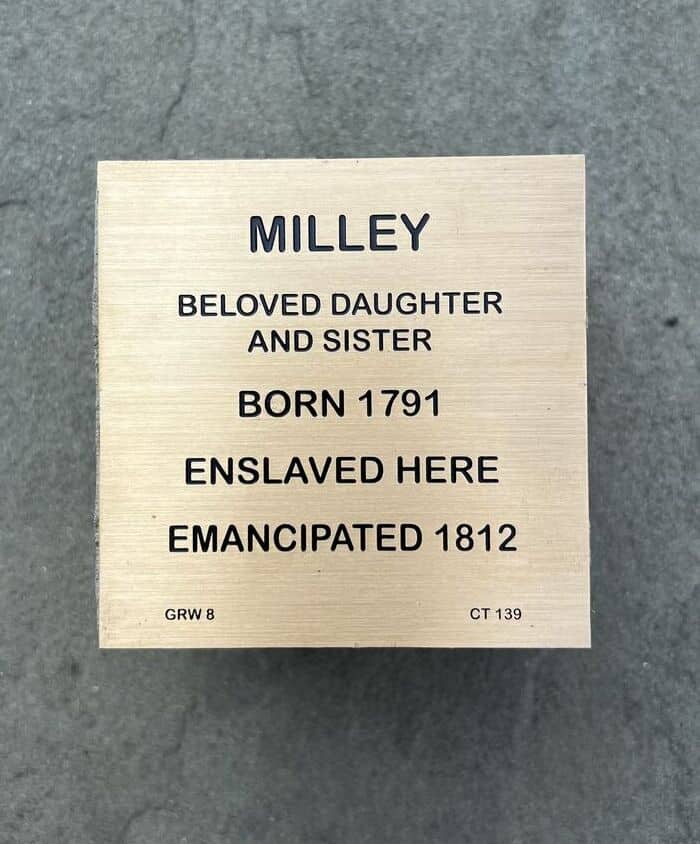

Milley

Milley was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. She was the second child of Cull Bush Sr and Patience, who were also enslaved by the Bush family. We know that Milley lived in the Bush household with her family until the age of 6. We also know that she is no longer there by the age of 16. Evidence shows that after the death of David Bush, the Bush family began to send Cull and Patience’s daughters out to serve in other households once they were old enough to work independently.

Milley was willed to David’s daughter, Charlotte, after his death, and would have served her, or had the money for her labor sent to Charlotte, until she was legally freed on her 21st birthday by the Gradual Emancipation Acts. Knowing this, we are unsure where Milley was living at age 21. Charlotte had married and started her own household in Stamford a few years before Miley turned 21. Records show that a Black woman was living in the Stamford house, but we cannot know if it was Milley. No records of her in freedom have been found. If you have any information about Milley, please contact Christopher Shields at cshields@greenwichhistory.org.

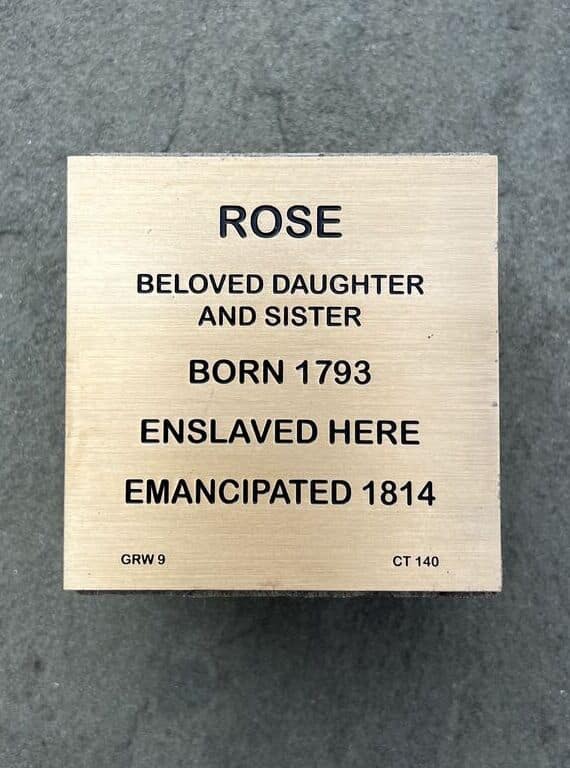

Rose

Rose was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. She was the third child of Cull Bush Sr and Patience, who were also enslaved by the Bush family. We know that Rose lived in the Bush household with her family until the age of 4. We also know that she is no longer there by the age of 14. It appears that after the death of David Bush, the Bush family began to send Cull and Patience’s daughters out to serve in other households once they were old enough to work independently.

Rose was willed to David’s daughter, Grace, after his death, and would have served her, or had the money for her labor sent to Grace, until she was legally freed on her 21st birthday by the Gradual Emancipation Acts. As Grace did not marry or move from her parents’ house before Rose’s 21st birthday, it is likely that Rose remained a maid for hire until she came of age. No records of her in freedom have been found. If you have any information about Rose, please contact Christopher Shields at cshields@greenwichhistory.org.

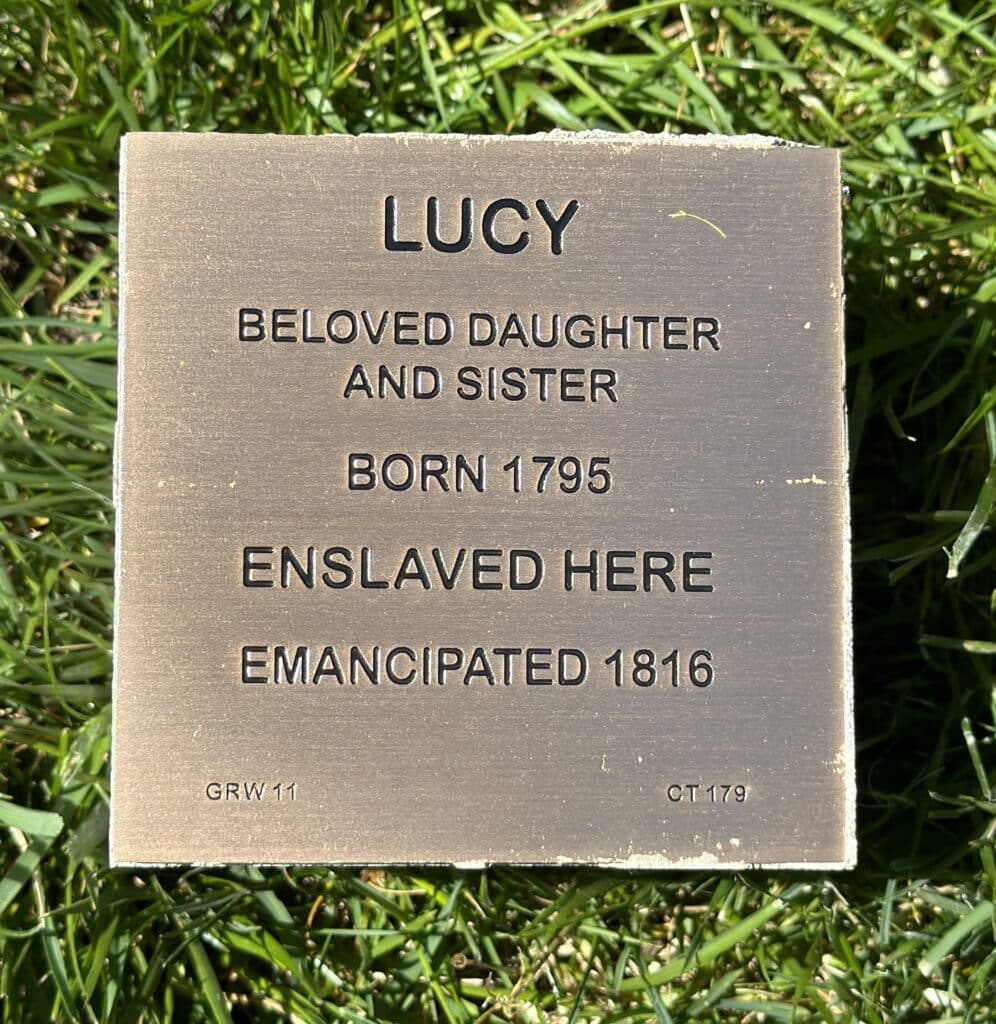

Lucy

Lucy was one of the sixteen enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. She was the fourth child of Cull Bush Sr and Patience, who were also enslaved by the Bush family. We know that Lucy lived in the Bush household with her family until the age of 5. We also know that she is no longer there by the age of 15. It seems that after the death of David Bush, the Bush family began to send Cull and Patience’s daughters out to serve in other households once they were old enough to work independently.

No records on Lucy have been found after she left the Bush household. If you have any information about Rose, please contact Christopher Shields cshields@greenwichhistory.org

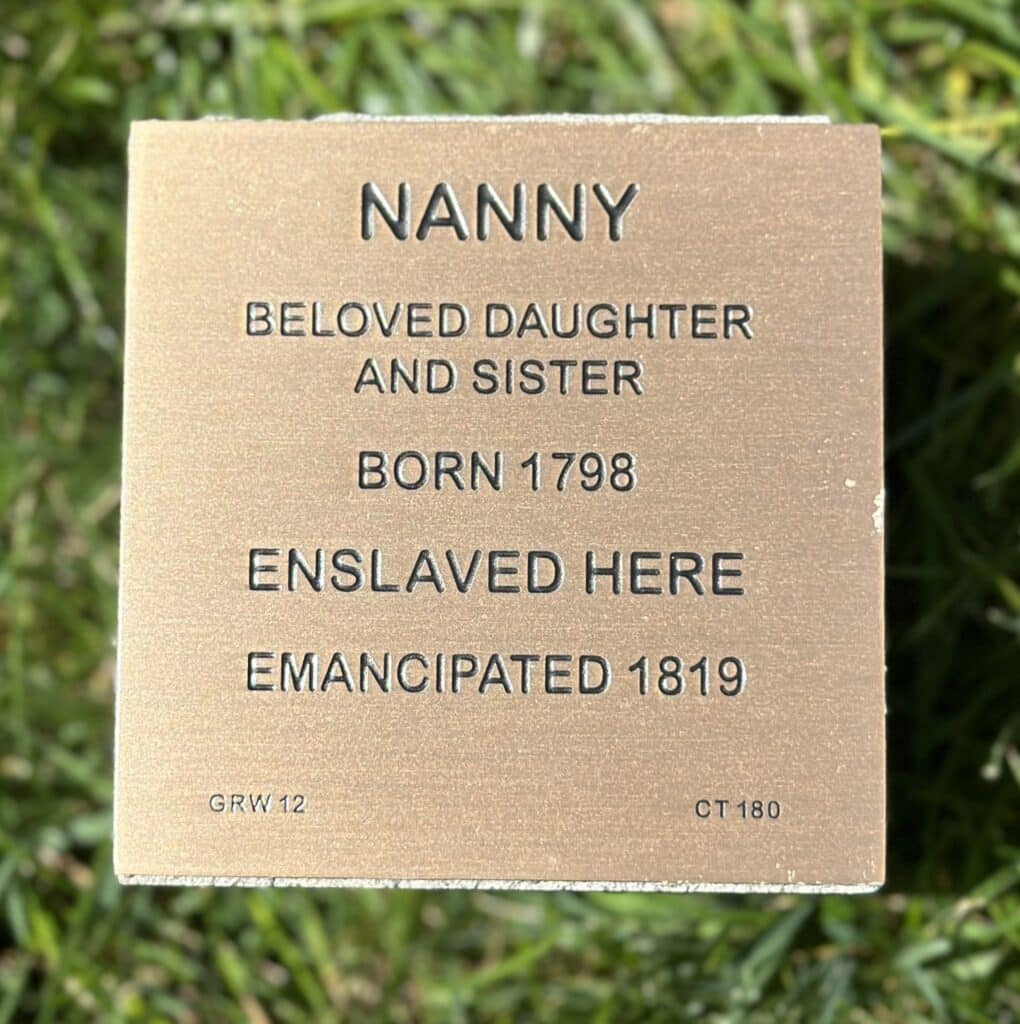

Nanny

Nanny was one of the sixteen enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. She was the youngest daughter and fifth child of Cull Bush Sr and Patience, who were also enslaved by the Bush family. We know that Nanny lived in the Bush household with her family until the age of 3. We also know that she is no longer there by the age of 13. Evidence points to the idea that after the death of David Bush, the Bush family began to send Cull and Patience’s daughters out to serve in other households once they were old enough to work independently.

No records on Nanny have been found after she left the Bush household. If you have any information about Rose, please contact Christopher Shields cshields@greenwichhistory.org

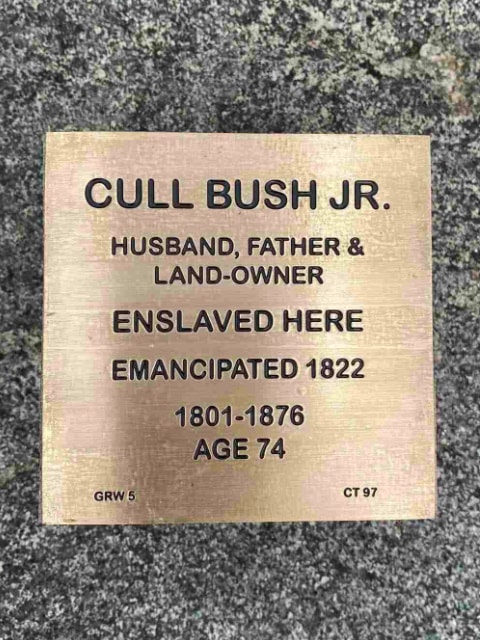

Cull Bush Jr.

Cull Bush Jr was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. He was the youngest child, and only son, of Cull Bush Sr and Patience, who were also enslaved by the Bush family.

Unlike his five older sisters, who were sent to work in other households once they were old enough, Cull Jr grows up in the Bush household with his mother. His father, who was freed just a year after Cull Jr was born, lived nearby and was likely a continued presence in his life.

Thanks to the Gradual Emancipation Acts, Cull Jr was freed when he turned 21 years old. He built a home next to his father’s in Cos Cob, just down the street from the house where his mother is still enslaved. In freedom, he married a woman named Cordelia, and together they had nine children. The descendants of these children continued to live in the area for generations to come. Some still live locally to this day.

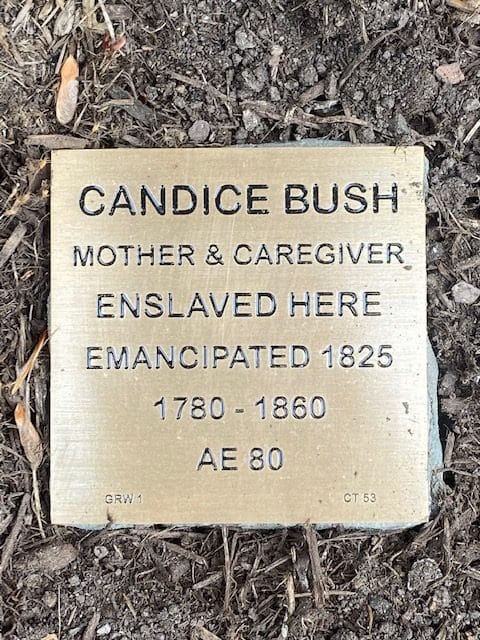

Candice Bush

Candice Bush was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. Our earliest known rerecord of Candice is in the first United States Census in 1790, in which she is listed among the enslaved. She was 10 years old.

Candice would remain enslaved to the Bush family until just before her 45th birthday in 1820. By the laws of the time, this was the oldest an enslaved person could be and still qualify for emancipation.

In freedom, Candice formed a household in Hangroot with her daughter, Hester, and her grandson, William. She would live in this house, with the ones she loved, until her death in 1840.

Candice is buried in Union Cemetery. She and her daughter are the only the only formerly enslaved people in Greenwich to have headstones.

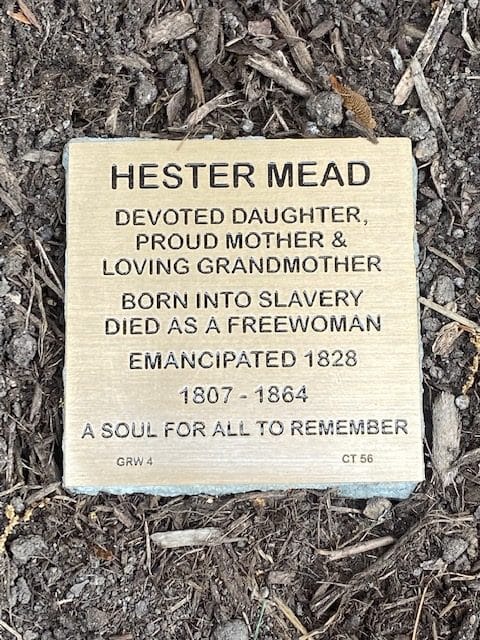

Hester Mead

Hester Mead was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. She was the last of eight enslaved children born there. Her mother, Candice, had been bound by the Bushes since she was a small child.

Thanks to the Gradual Emancipation Act, Hester became free upon her 21st birthday and lived the rest of her life in freedom. She had two sons, William and Charles, and by 1850 was living in a house of her own with her son, William, and her mother, Candice, in the free Black community of Hangroot.

Hester built a legacy. In her will, we can see that she possessed not only money, but also fine dresses, silver, and books, showing that she could read. She divided this wealth between her granddaughters. She also sets aside money for headstones to be placed for both her and her mother. This makes Hester and Candice the only formally enslaved people in Greenwich with headstones. They stand to this day, as a testament to Hester’s ability to succeed in a world that was stacked against her.

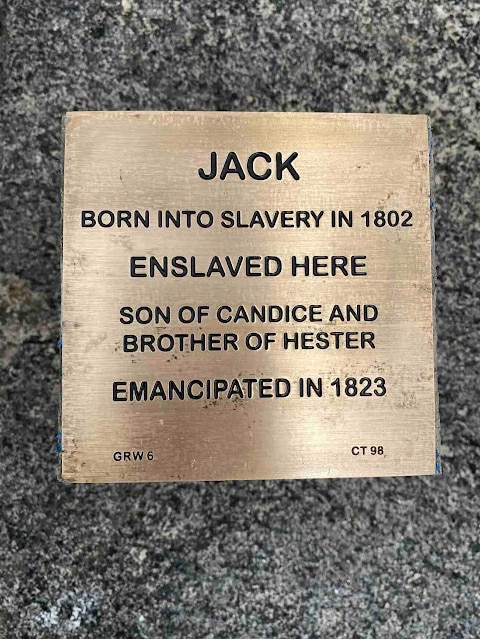

Jack

Jack was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. He was the oldest child of Candice Bush and the brother of Hester, who were also enslaved by the Bush family. Jack was among the last of the enslaved children born in the Bush-Holley House, along with his sister, Hester, and their peer, Cull Jr. However – unlike the children born the decade before – Jack, Hester, and Cull Jr all lived and worked at the Bush household until they came of age. This meant that Jack had the benefit of growing up with his mother and a tight-knit family group, which was not a common experience for enslaved children of the time.

Jack, Hester, and Cull Jr were all freed by the Gradual Emancipation Acts when they turned 21 years old. Once he was a free man and his choices were his own to make, it appears that Jack chose to leave Greenwich for good. We have not yet discovered records indicating where Jack went to build his new life. If you have any information about Jack, please contact Christopher Shields at cshields@greenwichhistory.org.

Charles

Charles was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. Unlike most of those enslaved by the Bushes, Charles does not appear to be related by blood to the other enslaved individuals in the house. Our earliest known rerecord of Charles is in the first United States Census in 1790, in which he is listed among the enslaved. He was a young teenager.

Charles around 20 when David Bush died in 1797. He was named in the will’s inventory, but he was not willed to anyone in particular. Three years later, Charles is gone from the Bush household along with the only other two enslaved people named in the inventory but not willed to anyone in particular; Jupiter and Peggy. It is likely that they were sold or given away during this time.

We do not know what happened to Charles after he left the Bush household. As he was born before the passing of the Gradual Emancipation Acts, his freedom was not guaranteed by law. There was a free man named Charles Moore in Greenwich of the right age and time to be Charles, but we cannot know if that was him or another. If you have any information about Charles, please contact Christopher Shields at cshields@greenwichhistory.org.

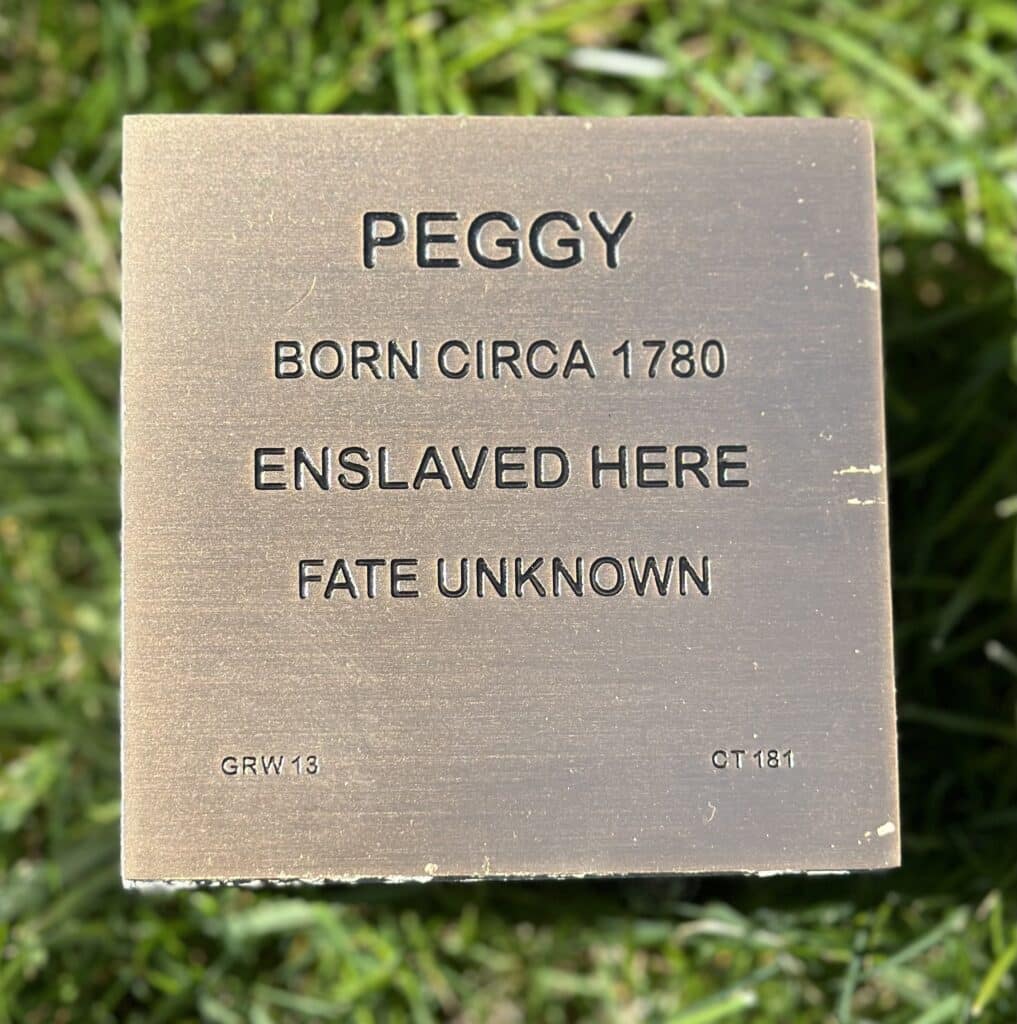

Peggy

Peggy was one of the sixteen known enslaved people held at the Bush-Holley House. Unlike most of those enslaved by the Bushes, Peggy does not appear to be related by blood to the other enslaved individuals in the house. Our earliest known rerecord of Peggy is in the first United States Census in 1790, in which she is listed among the enslaved. She was around 10 years old.

Peggy was a teenager when David Bush died in 1797. She was named in the will’s inventory, but she was not willed to anyone in particular. Three years later, Peggy is gone from the Bush household along with the only other two enslaved people named in the inventory but not willed to anyone in particular; Jupiter and Charles. It is likely that they were sold or given away during this time. We do not know what happens to Peggy after leaving the Bush household. If you have any information about Charles, please contact Christopher Shields cshields@greenwichhistory.org

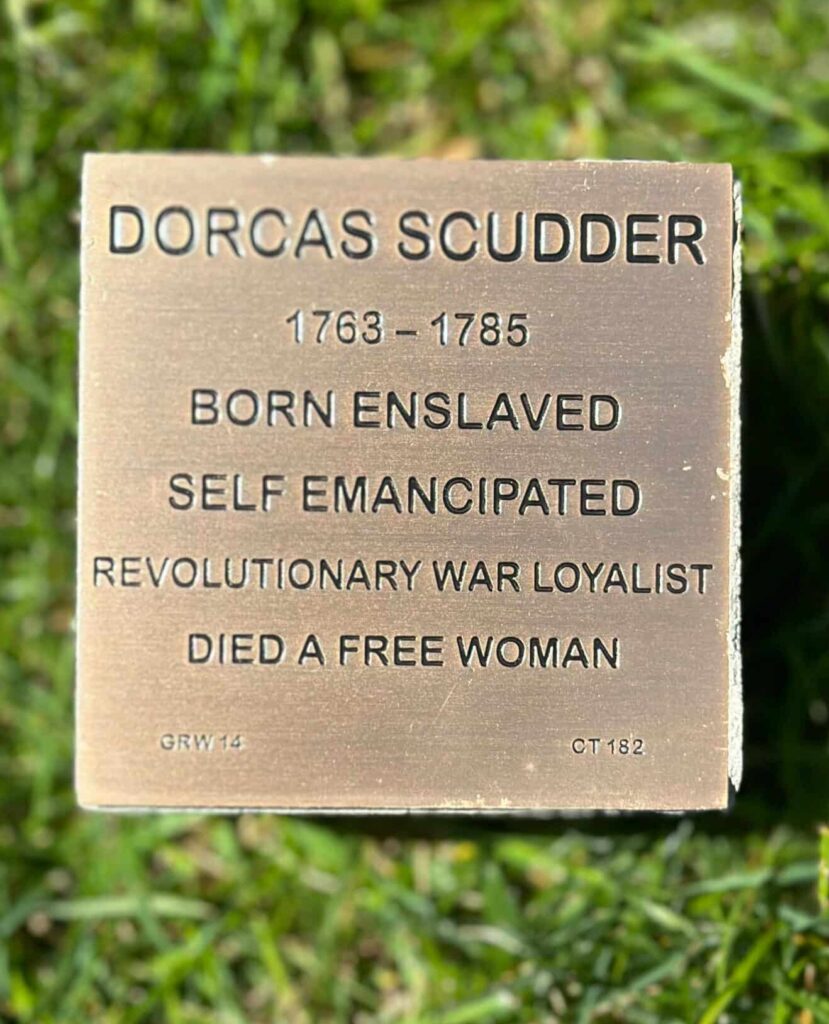

Dorcas

Dorcas is the earliest of the 16th known enslaved individuals held by the Bush family. She was originally enslaved by Sarah Bush (then Sarah Isaacs) and her first husband Benjamin Isaacs in Norwalk. She is willed to Sarah upon Benjamin’s death in 1775. Sarah remarries and moves into the home of her new husband, David Bush, in 1777. Dorcas was to go with her but it is unclear if Dorcas ever arrives in Cos Cob.

It appears that in chaos of the moved and the marriage, Dorcas finds the chance to flee. Only 14 years old, Dorcas self-emancipates and joins the British Army. By this time, Britain had promised freedom to any enslaved individual who joined their cause and promised to end slavery in the colonies if they won the war. Several others enslaved by the Bush family also joined the British army during this time.

After the war, the British Army sent Black Loyalists to Canada to prevent them from being re-enslaved. In 1783, Dorcas boarded the ship Concord for Port Mattoon, Nova Scotia. In 1784, Port Mouton burned to the ground. She then moved to Chedabucto Bay, later renamed Guysbourgh. In the winter of 1785, The British supply ship sending aid to the Loyalist population in Guysbourgh was overtaken by Americans. Most of the town starves. It is unknown if Dorcas was among the survivors.