For over a century, Greenwich has been home to some of the most picturesque gardens in the United States. Designed by leading 20th-century landscape architects like the Olmsted Brothers and Marian Cruger Coffin, these sprawling pleasure gardens often included sunken pools, sculpted fountains and an array of native and exotic plants. Beyond their beauty, the gardens also served as community gathering places for fetes and fundraisers, or, when the gates were locked shut, private escapes for the wealthy elite who owned them. Many gardens also saved space for vegetable patches and orchards, both to feed the families who lived on the estates and to help fellow citizens in times of need. The gardens that emerged in the early part of the 20th century were important markers of status and works of art that fed body and soul; however, while the names of their designers and even the titles of the estates themselves survive in our collective memory, the people who actually maintained the elaborate structures tend to slip through history’s fingers.

The gardeners who cared for Greenwich’s landscapes up until the 1930s were historically male and either African-American or immigrants, typically from European countries. It is likely that no documentation survives to link the majority of these men to the work they did to breathe life into the golden age of American gardens, but a few of them gained enough notoriety to be mentioned in the local papers. Others still would leave a lasting mark on Greenwich horticultural history. Their stories, or the lack thereof, remind us that a historical society’s work is a constant battle against time, and that our choices about whose story to preserve can impact historical understanding and identity for generations to come. Here are a few of those stories, pieced together from newspaper articles, census records and Greenwich Historical Society materials.

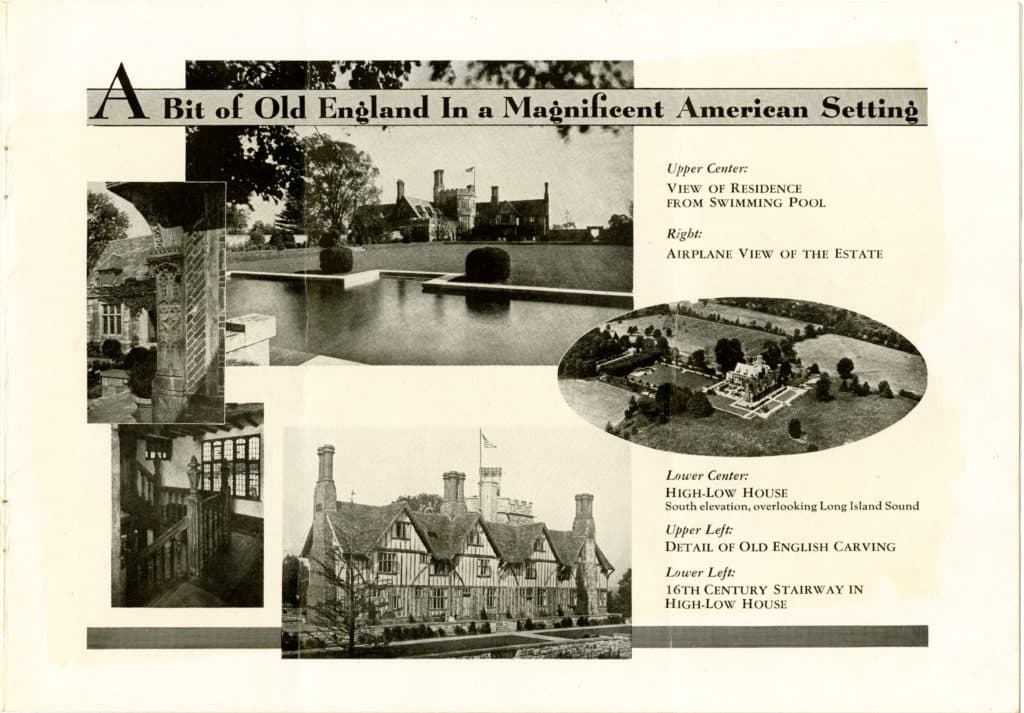

Alonzo Merritt was an African-American man born in the Stanwich neighborhood of Greenwich in September 1839. His family history is somewhat difficult to parse: census records seem to indicate that his parents were Harry and Harriett Merritt, while his obituary states that his parents were Harry and Eliza Roberts Merritt. It’s hard to say which is more likely to be correct, as the early censuses did not record the relationships among family members, and the newspaper could have confused the name of Alonzo’s mother with that of his daughter, Eliza Matilda Dalton. Either way, Alonzo Merritt likely grew up in Hangroot, the historically African-American community at the intersection of Round Hill Road and Horseneck Brook. Merritt would have grown up surrounded by free African-Americans, including men and women who remembered Africa and who lived through enslavement. At some point between 1860 and 1870, Merritt married Julia Ann Haley, with whom he had four children. By 1900, the family had moved to Cassidy Park, a community at the far eastern edges of Hangroot, near where Greenwich Hospital stands today. Merritt would live in this neighborhood for the rest of his life, sometimes joined by his sister and nephew.

According to a notice in the Greenwich Graphic, Merritt began working for Mary A. Lockwood in 1889. This complimentary blurb in the paper is the only known reference to Merritt as a gardener, rather than a “laborer” or “farm hand.” He continued working up until a few months before his death at 87 on July 16, 1927, although no record shows if he still worked for the Lockwood family. According to his obituary, Merritt was well loved throughout the town, known for his smile and his hard work, and his funeral at the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church was well attended.

For more information about the Hangroot community and the African-American experience in early Greenwich, visit historian and genealogist Theresa Vega’s website.

A. Foster Higgins house

This photograph of the A. Foster Higgins house in winter dates from around 1930, approximately 40 years after Schultz would have stopped working at the estate. Greenwich Historical Society Collection.

From Greenwich Historical Society Collection.

Herman Schultz was born in 1834 in what was then known as the Kingdom of Prussia, and which now might be one of several Central European countries, most likely Germany. His exact year of immigration is unknown, but he was living in Greenwich with his wife, Anna Schultz, by 1870. Schultz earned repeated glowing praise from the local newspaper for his flowers and produce, which he grew at the residence of New York financier A. Foster Higgins on East Putnam Avenue. Known today as the Tomes-Higgins House, the historic building and likely the grounds were designed by the famous architect Calvert Vaux, who worked with Frederick Law Olmsted on the plans for Central Park. Schultz managed the flowers, grounds and greenhouse at the estate, including the piece of land across the street between Park Place and Park Avenue, which used to be called Higgins Park and is believed to have once held a vegetable patch. On these lush grounds, Schultz is reputed to have grown strawberries 5½ inches in circumference, as well as Parisian pansies in a range of colors, and trained a single rose bush to climb 50 feet around the greenhouse, onto which he grafted 12 different varieties of roses. He disappeared from the public record after 1891, with no notice of his death or burial in Greenwich.

Ernest Dehn was born in 1856 in a town called Schwetzkow, Germany, which at the time was part of the Province of Pomerania in the Kingdom of Prussia. After 1945, the village, which is now known as Świecichowo, became part of Poland. It is unclear how long Dehn’s family remained in Schwetzkow, because he emigrated from the city of Bremen in 1888 to the United States. Dehn traveled with a man from Switzerland named August Bertolf, who would become his lifelong business partner and friend. The pair first arrived in Illinois, where they worked on the landscaping team for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1892‒1893; 1893 was also the year that Dehn became a naturalized citizen of the U.S.

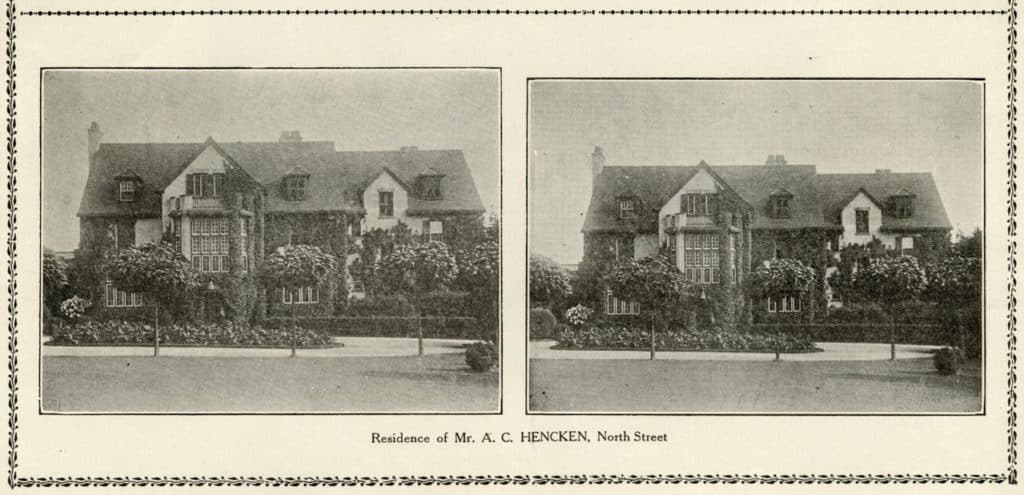

Albert C. Hencken House

Albert C. Hencken lived at 341 North Street, circa 1905 only a few houses down the road from the Dehn & Bertolf Nursery. His house still stands, though it has been extensively remodeled.

From Greenwich Historical Society Collection.

Dehn moved to Greenwich sometime before January 1900, when he and Bertolf purchased a piece of land on North Street near the Greenwich Country Club, which would become their nursery and landscaping headquarters. Initially, the ads in the papers only sported Dehn’s name; he worked mainly as a landscape gardener, but also grew nursery stock for sale. By 1902, Bertolf’s name had joined Dehn’s on the advertisements, and the duo landscaped great estates like those of Frank Squier and H. M. Day in Belle Haven, the A. C. Hencken residence on North Street and the Havemeyer School. Dehn retired from the business in 1916, and in 1917 it was announced in the paper that the business formerly known as Dehn & Bertolf was now Bertolf Brothers, after the sons of August Bertolf. After his retirement, little is known about Dehn’s activities. He had already been a widower by the 1900 census, and he did not appear to have any children. The papers mention that he was involved in charity work, like arranging for shrubs and flowers at charity balls and being part of the committee for a celebration in honor of the men and women returning from World War I. Dehn died on April 12, 1928, a few months after August Bertolf.

The Havemeyer School

The Havemeyer School was donated by Henry O. Havemeyer in 1892 and opened for classes in 1894. The building now serves as the home for the Greenwich Board of Education and Greenwich Adult and Continuing Education. Dehn & Bertolf got the Havemeyer school contract in February 1915.

From Greenwich Historical Society Collection.

The gardeners of Greenwich were essential to the evolution of the town from an agricultural community to a center of affluence and opulence. They brought the visions of talented designers to life, and continued to care for them for long years after the architects had moved on to other ventures. However, although photographs exist of these estates and even of their owners, there are no known photographs of any of the men mentioned above or of countless others. With the tens of thousands of images in the Greenwich Historical Society’s collection, only a portion of Greenwich history is told. This is a sobering reminder that the decisions we make as archivists and local historians will shape the historical narrative for everyone who comes after us. It is also a great source of hope: by choosing to tell the more obscure stories, and by appreciating all facets of our modern Greenwich community, we can ensure that future generations can see Greenwich in its vibrant entirety.