The hearth was the heart of a colonial home. It provided people with warmth, light, and most importantly, food. Almost everything a colonial family ate would have been prepared on the hearth. In this mini-series, I am going to show you how I make some of my hearth cooking staples.

Please note that not all fireplaces, even in colonial buildings, are equipped to be a cooking hearth. I am also a professional with years of training. Please do not try these recipes in a fireplace at home.

If a recipe can be replicated on a campfire or a stovetop, I will give you follow-along instructions to do from home. I only ask that all campfires are safely constructed, ovens are used with care, and a responsible adult is present at all times.

Today’s Topic: Receipts

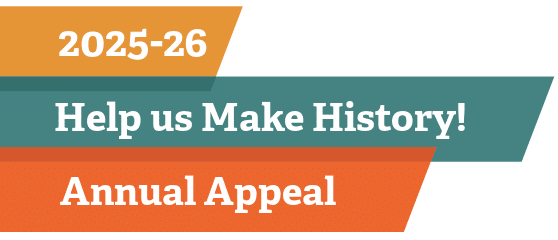

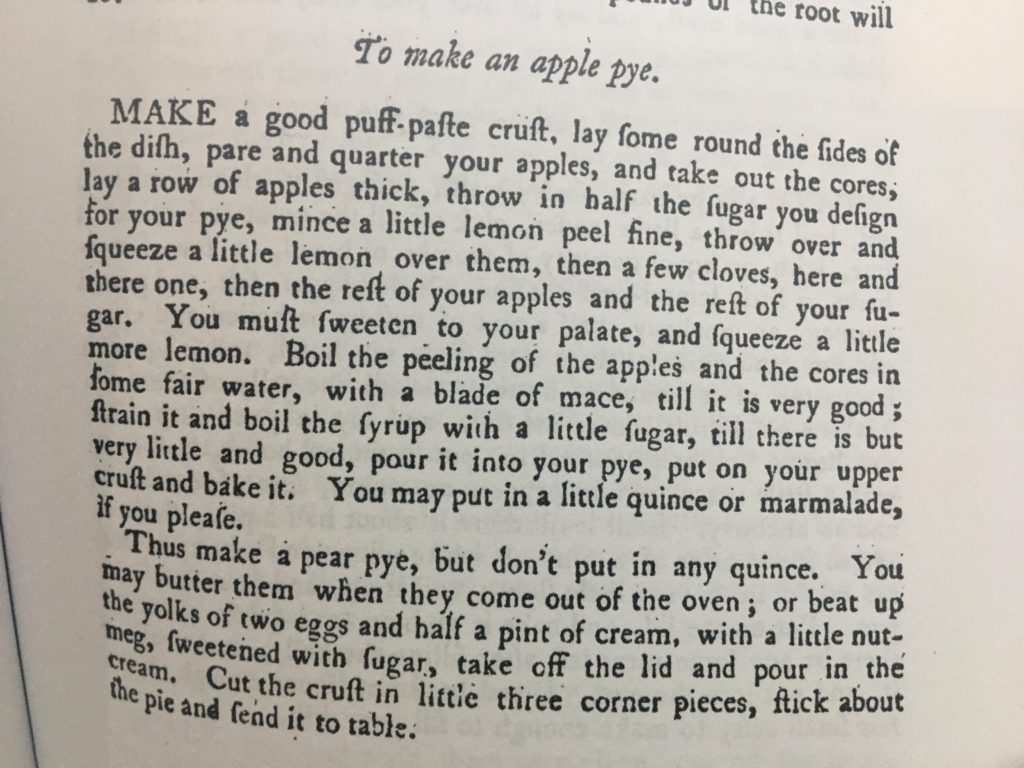

The first thing to know about colonial cooking is that written recipes were called “receipts.” Pictured above is a colonial receipt owned by Ann Bush in the late 1700s, which we have in our archives. On that single page, there is one recipe for gingerbread and another for a loaf cake. Notice how short they are; receipts were meant to jog the cook’s memory, not teach others how to cook.

In the colonial era, girls began to cook by their mother’s side as soon as they could stand on their own. They learned dozens of different recipes by the time they were teenagers. Each recipe was memorized and only written down if rarely used or shared with others. Instructions to others were sparely written, as the others were presumed to know how to cook.

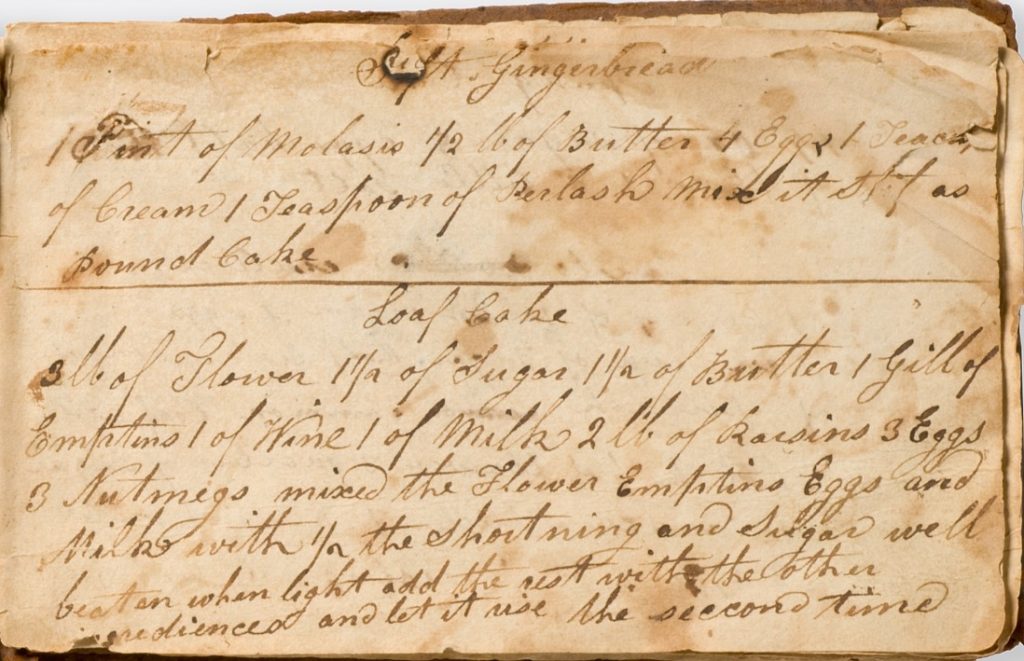

Colonial cookbooks were short on instructions, too. For example, the following apple pie recipe assumes you already know how to make a crust, lets you decide what amount of sugar and spice to use, and tells you simply to bake it while giving you no idea about how much heat or time was required!.

As I share my favorite colonial recipes with you, I might say “cook until done” or “add to taste,” and you might wonder “how long is that?” or “how much do I add?”

Embrace the uncertainty as part of authentic colonial cooking!