Thomas Connors | The Magazine Antiques | January 3, 2022

Home. For most of us, it is the heart’s happy place. For creative types, it can be prison or paradise, a cage that keeps one from working, or the setting where one works best. And then there are those like Frank Lloyd Wright and Claude Monet. The architect’s estate, Taliesin, in the hills of the Wisconsin countryside, was both abode and manifesto—a working studio and classroom, where acolytes gathered and often gave their all to learn from the ever-confident master. Monet turned his home in the French village of Giverny into a place both of this world and apart from it—a garden of the artist’s mind as much as of the earth.

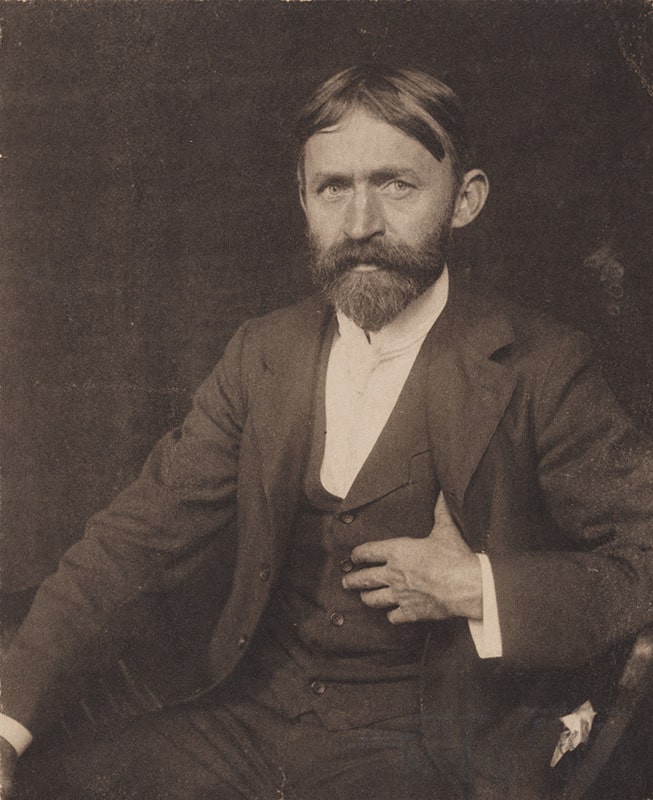

After making a name for himself in New York City in the 1880s, painter John Henry Twachtman (Fig. 3) left Manhattan, settling in Greenwich, Connecticut. Not unlike Wright in Wisconsin and Monet in Giverny, he made a home there that became central to his artistic expression, not merely a residence. Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman, an exhibition organized by the Greenwich Historical Society—its debut will be delayed by clean-up necessitated by Hurricane Ida in September—looks beyond the surface of images by this American impressionist to explore how the artist’s immediate environment, his home, shaped his work—and how he shaped that home to better support his vision of how to construct a picture.

The Cincinnati-born son of German immigrants, Twachtman studied in Munich and Paris. Between these sojourns, he returned to Cincinnati, where, in 1881, he married Martha H. Scudder, the daughter of a physician with artistic leanings of her own. In 1889 he moved his family (by now he was the father of three) to New York, where he had previously begun to participate in the city’s art scene, exhibiting with the Society of American Artists (formed as a progressive alternative to the conservative program of the National Academy of Design) and joining the Tile Club, a decorative arts–driven entity whose membership included Twachtman’s friend William Merritt Chase and architect Stanford White.

Twachtman’s orientation toward Connecticut began in1878, when he and good friend and fellow painter J. Alden Weir boarded at the Greenwich farm of Edward and Josephine Holley, who later ran a boardinghouse overlooking the water in the Cos Cob area that became—thanks to Twachtman’s presence—the center of the Cos Cob arts colony. In 1888 Twachtman rented a cottage in Branchville, not far from a farm owned by Weir, who had acquired the property several years earlier. Two years later, thanks to a successful auction of his paintings and pastels at the Fifth Avenue Art Galleries and the financial security afforded by a regular teaching position at the Art Students League in New York, Twachtman made Greenwich his home, purchasing a small house on several acres in an area of derelict farms known as Hangroot. It did not take long for him to believe that he was in his true home. “To be isolated is a fine thing and we are then nearer to nature,” Twachtman wrote to Weir in 1891. “I can see how necessary it is to live always in the country—at all seasons of the year.”1

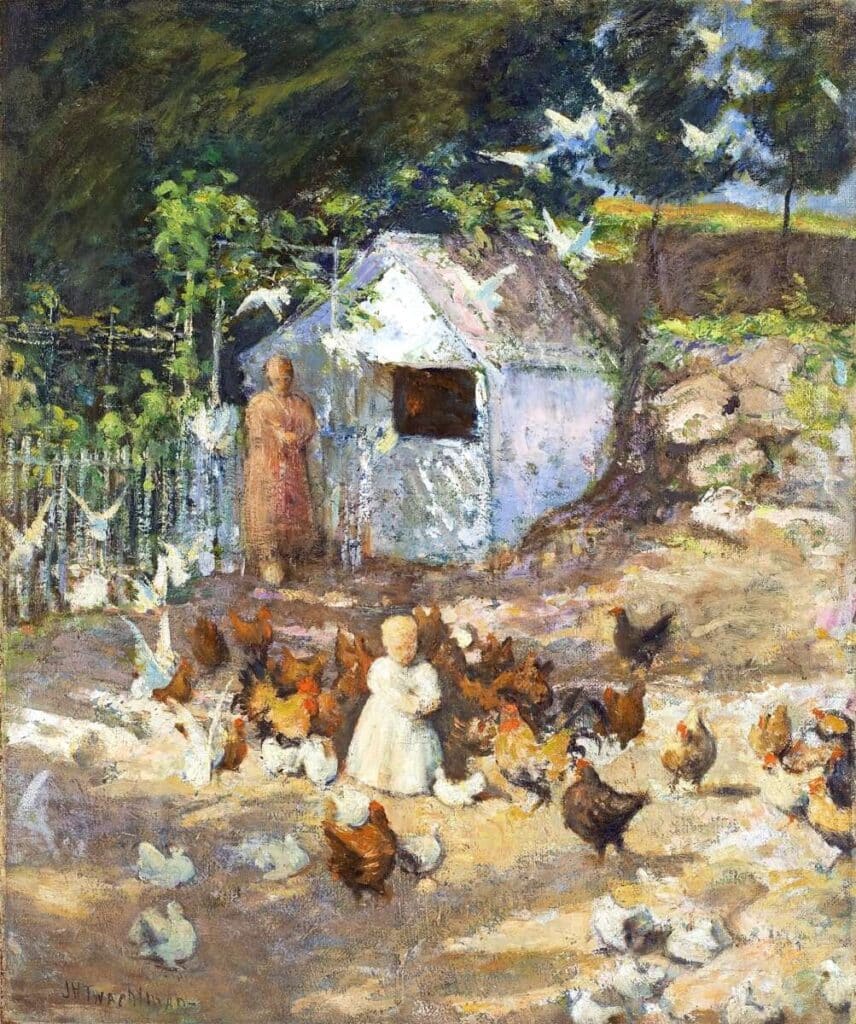

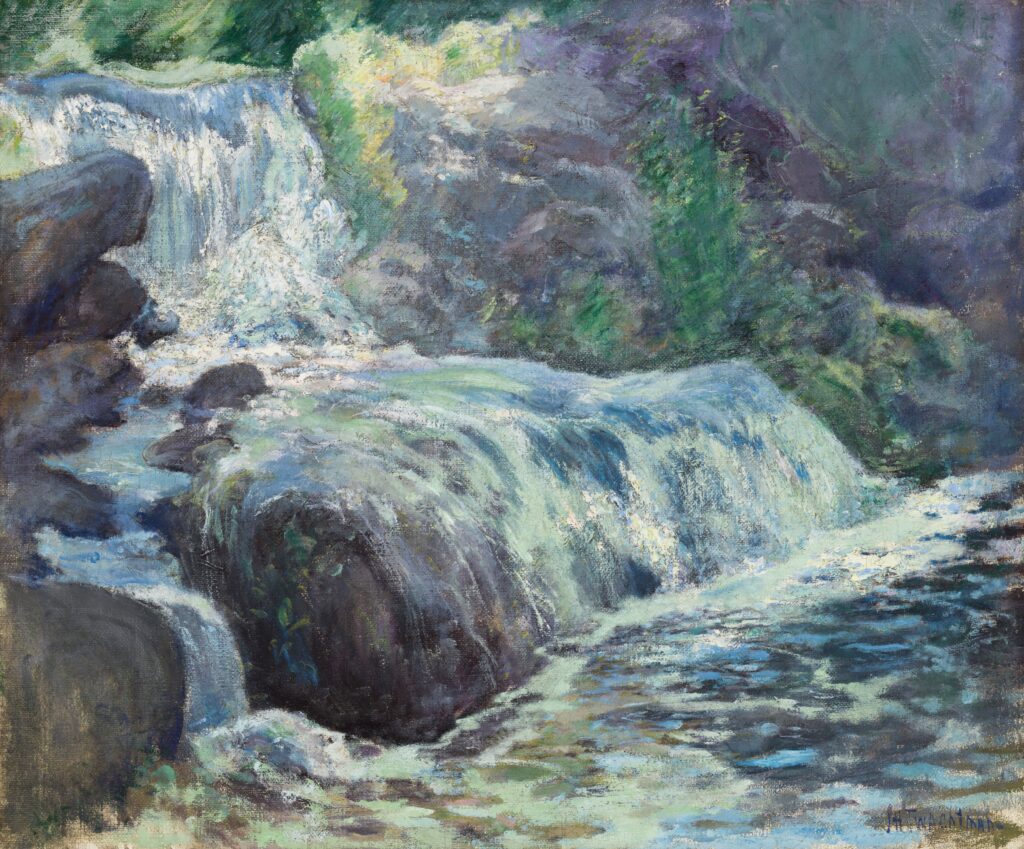

Twachtman’s property was a far cry from the grand estates that were already beginning to transform this rural corner of Connecticut, but it became, in its way, an environment as mediated as any that society’s elite were fashioning. Twachtman tinkered with the house, both expanding it to accommodate a growing family (Childe Hassam helped him lay a new foundation) and altering its profile to bring the structure into better sympathy with the terrain. While appreciative of the sometimes disjointed aspect of a purely natural surroundings (as opposed to calculatedly picturesque landscape design), Twachtman nonetheless put his hand to his land, laying out a flower garden, planting poplar and willow trees, erecting trellises and stone walls, and damming a section of a brook to create a swimming hole for his children.

Although the artist’s interventions can be seen as labors common to many a proud homeowner, they suggest a deeper impulse according to Life and Art curator Lisa N. Peters. An independent scholar whose previous work on the artist includes the 1999–2000 exhibition John Henry Twachtman: An American Impressionist, organized by the High Museum of Art, Peters has also compiled the Twachtman catalogue raisonné (jhtwachtman.org), recently launched in collaboration with the Greenwich Historical Society. “One could say that Twachtman felt the Greenwich landscape was worthy of divine status, an apotheosis if you will, which he achieved by memorializing it in his art,” Peters says. “His Greenwich home enabled him to fulfill a pantheistic existence, living inharmony with nature and thus, in a sense, being part of the natural world. By depicting what he created aesthetically, through architecture and the land itself, he turned his paintings into commentaries on his artistry, making the nature of art their true subject.”

While Twachtman captured myriad aspects of his property on canvas—the hills, the brook that ran through it—the house itself (still standing as a private residence) figured prominently in his efforts. The sense of it being at one with its setting is manifest in From the Upper Terrace (Fig. 1). Spun from the same palette as the garden and landscape around it, its saltbox form almost disappears into the diaphanous vista, save for the dark green of the trees behind it that push the structure forward. Captured from a closer vantage point in September Sunshine (Fig. 2), the house is more directly the subject, its whiteness obscured here and there by the green leaves of several trees. In the seemingly breeze-swept Hollyhocks (Fig. 4), it functions as a framing device, directing the eye to the pleasing pink of the flowers.

Over the years, Twachtman’s work had evolved from dark realism rendered with assertive brushwork toa lighter palette and more softly applied paint, an approach that produced particularly engaging results in wintertime images. Often executed en plein air, these pictures, such as Barn in Winter, Greenwich, Connecticut (Fig. 6), were a departure from the sentimental and more documentary cold season scenes typified, for example, by the work of the prolific George H. Durrie (1820–1863), who painted in New Haven a generation earlier. Speaking of one of Twachtman’s wintry canvases, fellow painter Thomas Wilmer Dewing remarked: “One feels the temperature, and recalls the scream of the blue jay, the black-green leaves of the sapling pines turning gray in the wind. It is like a page from one of Thoreau’s note books.”2

Whether he was depicting a view across an open field, a stream cascading over stones, or terracotta pots in the afternoon sun, Twachtman’s focus was sharp, but wide. “In painting his surroundings,” Peters notes, “you might say Twachtman took a romantic perspective, capturing not just what he saw, but also expressing what he felt. While capturing the essence of his sites, Twachtman did not seek a spiritual presence existing beyond the seen world. He felt poetic and uplifting experiences were in the here and now, in the feelings evoked by familiar places and by engaging with nature closely.”

In his later years (he died young, at age forty-nine, of a brain aneurysm), Twachtman spent time in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where, in rendering the built environment of piers, fish sheds, and the humble dwellings of fishermen, he combined slightly more solidly modeled forms with the impressionistic mode that had come to fruition in Connecticut. But, in a memorial tribute that appeared in the North American Review eight months after the artist’s death, it was his sympathy with nature that his country colleague, J. Alden Weir, remembered:

He was in accord with nature, winter or summer, and a day with him in the country was always a delight. The open fields with their long lines running into the landscape enticed one from the house on the hill-side to where the stream wandered through the valley, capable of transforming itself into a torrent at the approach of spring. Such will be recognized as the subject of many of Mr. Twachtman’s canvases, in which one is made to feel the spirit of the place and the delight with which his work was done.3

Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman was originally scheduled to be on view at the Greenwich Historical Society from October 6, 2021, to January 9, 2022. Due to storm damage inflicted by Hurricane Ida in September, the exhibition has been delayed. Consult greenwichhistory.org for updates.

1 John Henry Twachtman to J. Alden Weir, Greenwich, Connecticut, December 16, 1891, in Dorothy Weir Young, The Life and Letters of J. Alden Weir (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960), pp. 189–190. 2 T. W. Dewing, Childe Hassam, Robert Reid, Edward Simmons, J. Alden Weir, “John H. Twachtman: An Estimation,” North American Review, vol. 176, no. 557 (April 1903), p. 554. 3 Ibid., pp. 561–562.

Thomas Conners is a Chicago-based arts writer.