Connecticut Explored | IN THIS ISSUE: EAT UP! | Volume 23/Number 1/Winter 2024-2025

“You Can Imagine

What a Feast We Had”:

By Kelsie Dalton

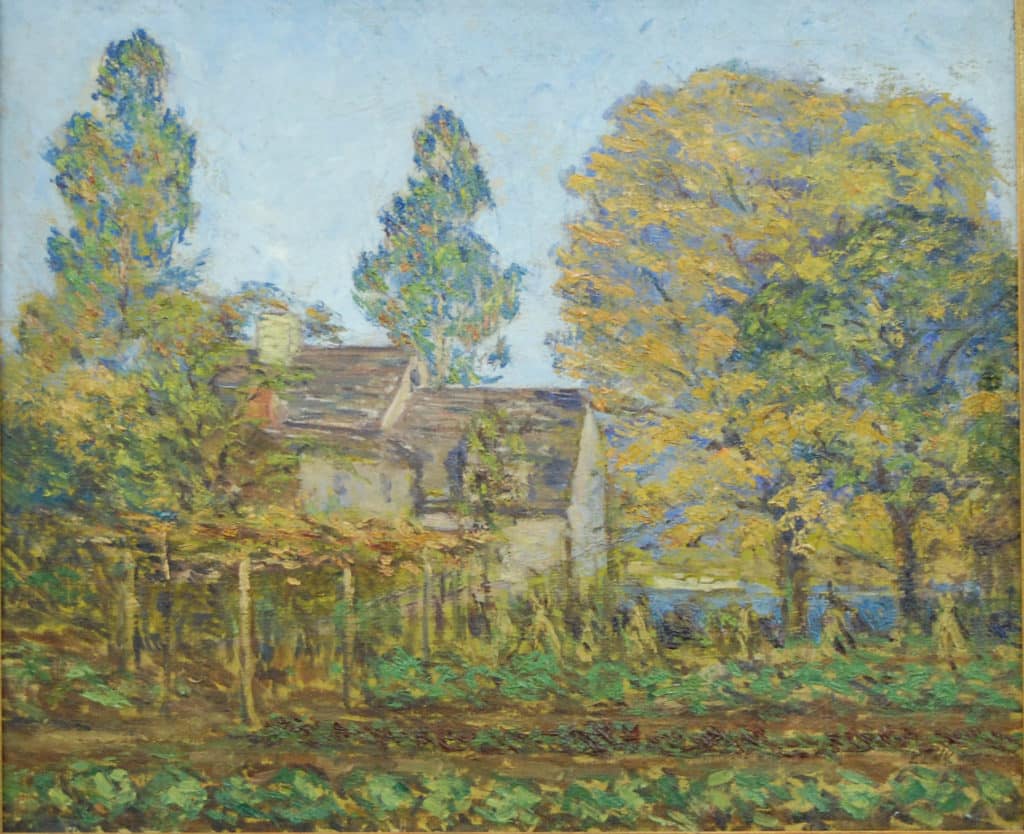

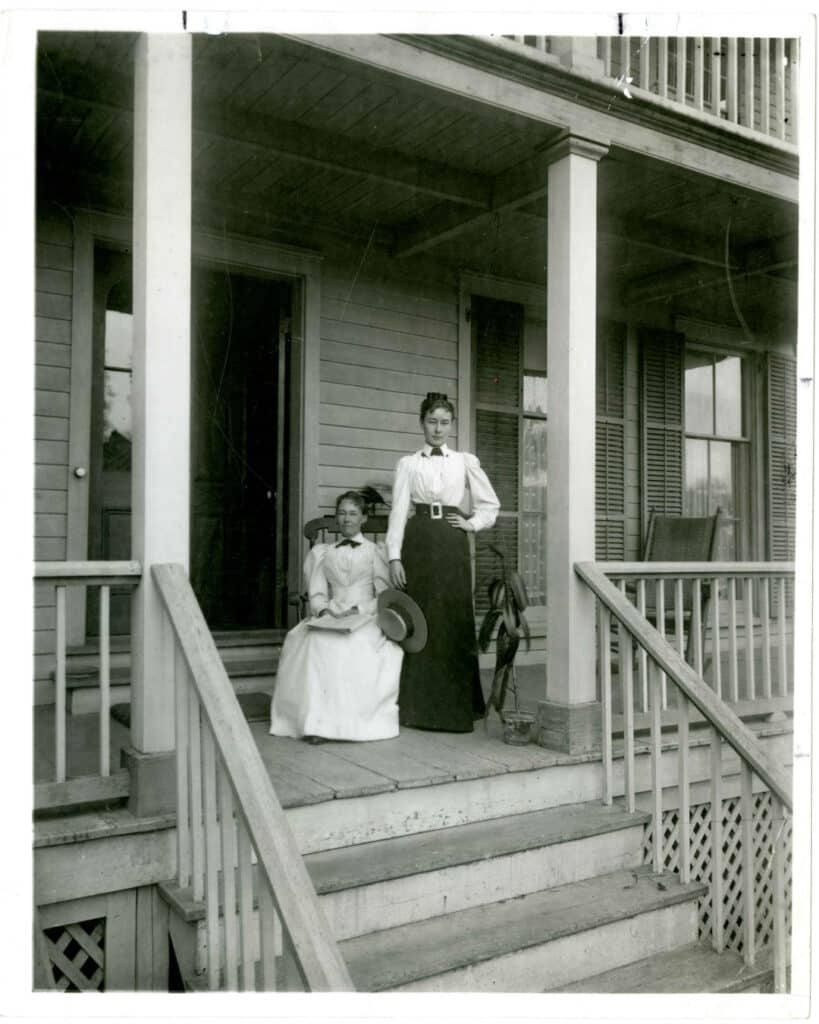

The Cos Cob Art Colony emerged as the cradle of American Impressionism in 1890, when the first classes from the Art Students League of New York hopped on trains to bucolic Cos Cob, a seaside neighborhood of Greenwich, Connecticut. Summer art sessions were first offered that year by John Henry Twachtman and Julian Alden Weir, two esteemed painters in the American Impressionist movement. Other famous painters like Childe Hassam and Theodore Robinson followed, eager to capture the beauty of the harbor and countryside. Their presence soon drew artists of all kinds—novelists, ceramicists, poets, and opera singers—to Cos Cob. The art colony was a hub of creativity for about 30 years. At its center was the Holley family boardinghouse run by proprietors Josephine and Edward Holley with the help of their daughter, Emma Constant.

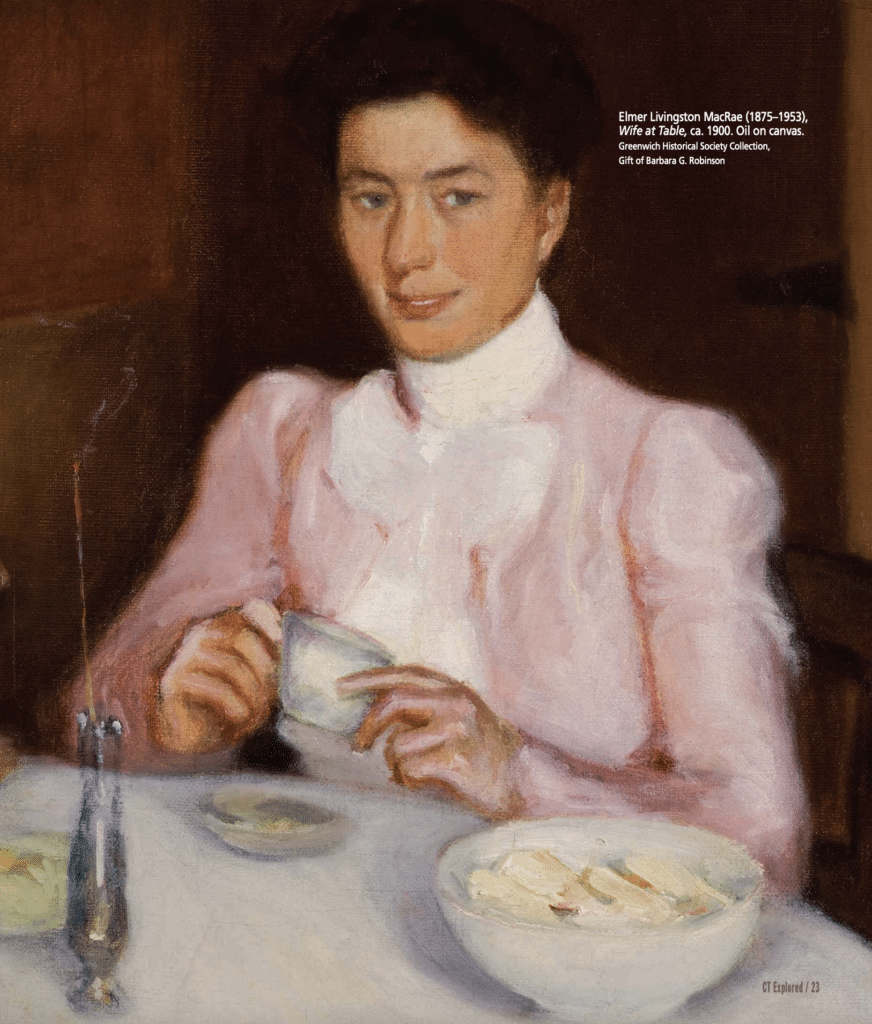

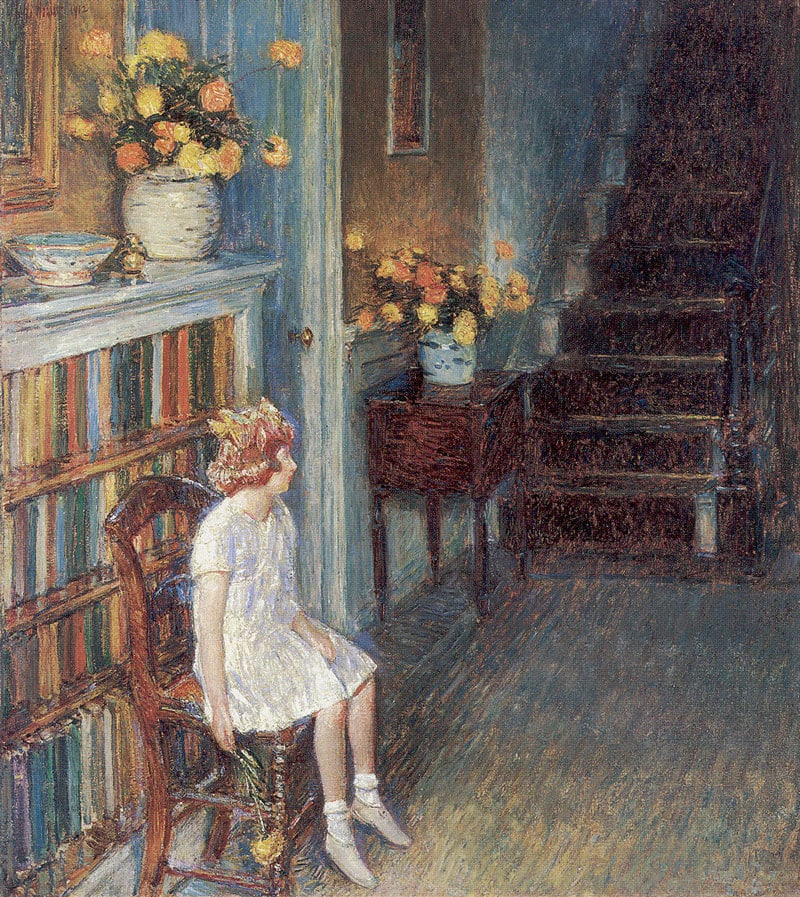

The Holleys kept a comfortable and inspiring home. The artists enjoyed cozy rooms full of natural light, which beckoned them outdoors to enjoy boating on the Mianus River, fishing and swimming in the harbor, and lazing in hammocks. One artist stayed for good: Elmer Livingston MacRae fell in love with Emma Constant in 1896, during his first summer at the house, and the two were married in 1900. They quickly took over the running of the boardinghouse and property.

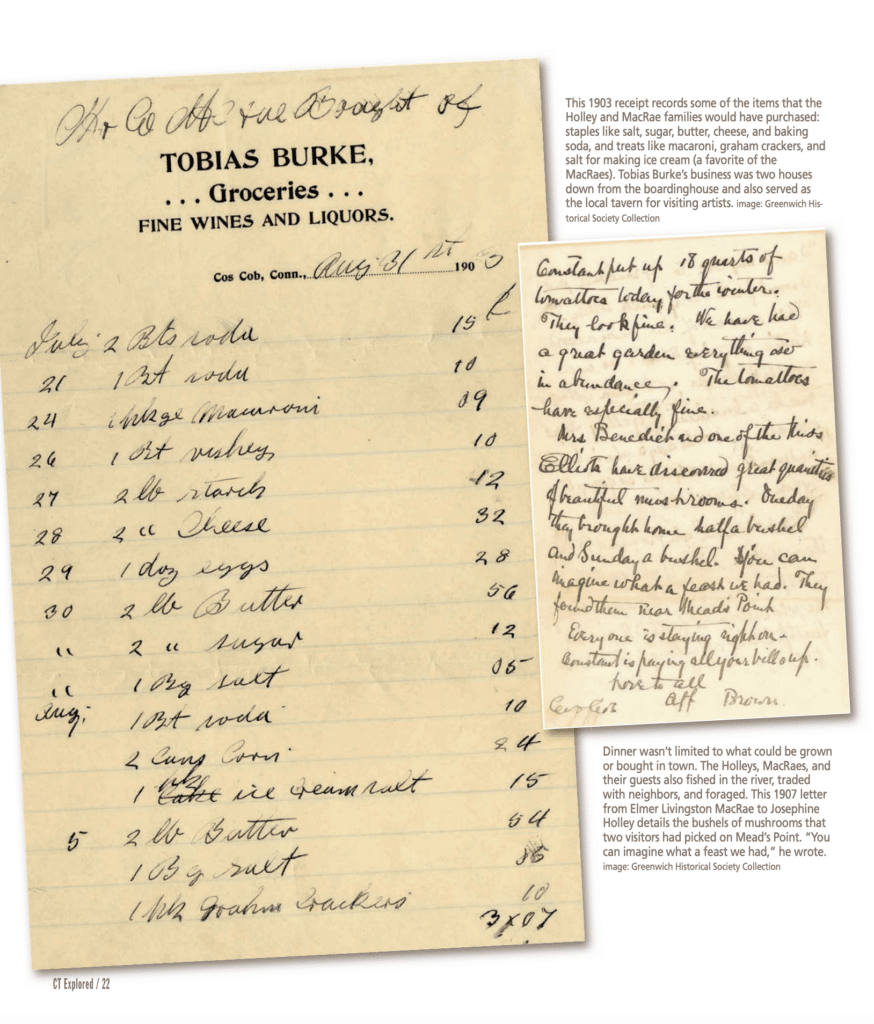

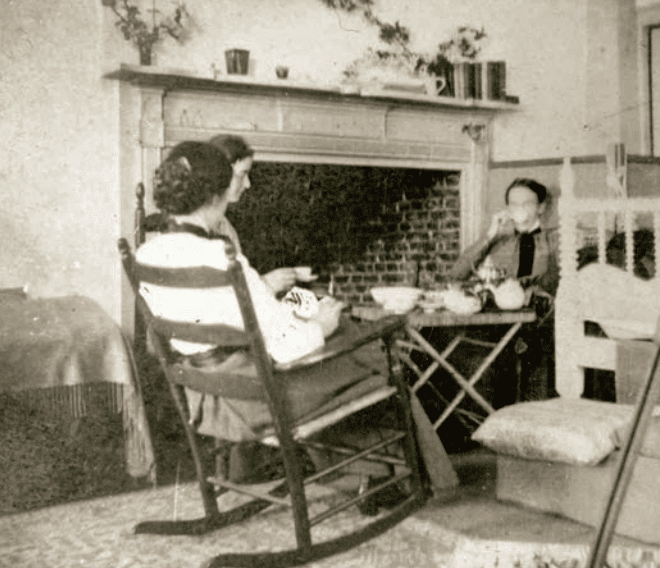

The Holleys and the MacRaes maintained beautiful gardens visible from every window of the Holley House. Their planting journals reveal a cornucopia of produce, including corn, onions, peas, beets, lettuce, okra, potatoes, beans, cucumber, cauliflower, tomatoes, grapes, and cantaloupe. This crop would be harvested and preserved in huge quantities to support the family and their paying guests throughout the winter. In his autobiography (Heyday Books, 2005), the muckraking journalist and art colony member Lincoln Steffens remembered, “We dined all together at one long table in a fine, dark, beflowered dining-room.”

The dinner table was also the site of a favorite game of Steffens and Twachtman. Each of them would take an opposing side on a polarizing topic they had chosen ahead of time—the nature of art or beauty being favorites. Once the two men had the battle lines drawn and their dinner mates were passionately defending one side or the other, Twachtman and Steffens would gradually change their positions until they were arguing for the other side. According to Steffens, “Our goal was to carry, each of us, all our party around the circle without losing a partisan.” He claimed that they were amazingly successful at it.

The dinner table was also the site of a favorite game of Steffens and Twachtman. Each of them would take an opposing side on a polarizing topic they had chosen ahead of time—the nature of art or beauty being favorites. Once the two men had the battle lines drawn and their dinner mates were passionately defending one side or the other, Twachtman and Steffens would gradually change their positions until they were arguing for the other side. According to Steffens, “Our goal was to carry, each of us, all our party around the circle without losing a partisan.” He claimed that they were amazingly successful at it.

These dinnertime dramas took place against the backdrop of reportedly delicious meals prepped by Emma Constant and whatever servants the family could afford to keep at the time. Some of their menus are recorded in Emma Constant’s letters to her mother. While smaller groups might warrant simpler meals (soups, clam chowder, and Welsh rarebit all show up with some frequency), special occasions merited banquets.

Emma Constant recounted their Thanksgiving dinner in a December 2, 1902, letter. The guest list included the artists Carolyn Campbell Mase, Charles “Ebe” Ebert, Mary Roberts Ebert, and Childe Hassam and his wife Maud. The table was laden with “turkey and a pair of ducks, oysters, soup, mince pie, biscuit glacé, candy, & c.” Just before dessert was served, the MacRaes presented each of the attendees with a gift “that roasted every ones weak points.” Ebe received an encyclopedia, hollowed out and filled with candy because he was so brainy. Mrs. Hassam was given a lobster with a diamond necklace inside because of “her saying one time that she had never got a pearl out of an oyster but she once got a diamond necklass out of a lobster.” Content with their feast and the promise of something sweet, they laughed at one another and themselves.

For over three decades, the Holley and MacRae families welcomed travelers into their family home and fed their creativity. Today, the boardinghouse is preserved as the Bush–Holley House, a National Historic Landmark on the campus of the Greenwich Historical Society. Visitors are still greeted by a full table: bowls of ice cream decorated with cherries, jars of preserved peaches and grape “jell,” and sumptuous holiday meals. While the food in the dining room might now be fake, every detail is authentic, culled from the Holley–MacRae papers in the archives. The heart of the Holley House still bustles as though an artist might be just around the corner, coming in from a day of painting en plein air, his appetite whetted and hungry for more.