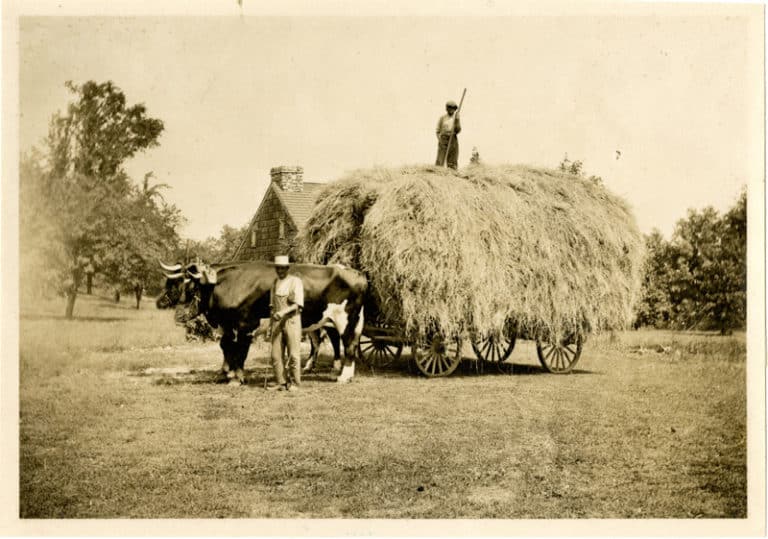

Now famously home to exclusive housing developments and luxury retailers, the Town of Greenwich began as an agricultural enterprise. Historically, this was a necessity. After the purchase of Greenwich in 1640 from the Munsee Indians, new settlers had to subsist on what they could produce, without dependable help from England. But the agrarian character of Greenwich extended far beyond its Colonial roots well into the 20th century, leaving a mark on the physical and cultural landscape.

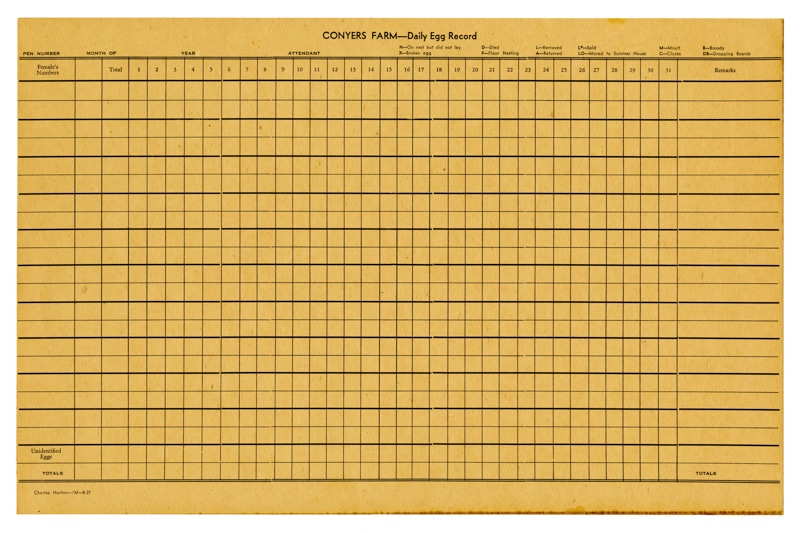

Some of the earliest and most extensive farming operations were started by families whose names will no doubt be familiar to any Greenwich resident: Mead, Ferris, Lockwood, French and Maher to name a few. Many of the best-known estates in town were farmed at some point, including Milbank and Tod’s Point (otherwise known as Innis Arden). In fact, a number of those exclusive housing developments mentioned above began as farms – and still carry ‘farm’ as part of their names as a result – like Conyers Farm, West Lyon Farm, and Baldwin Farms. Even after the days of pure subsistence farming, after industrialization and the explosion of urban development, farming was still seen as a necessary part of country life. Before the establishment of fast global trade, food production could not be completely outsourced.

Greenwich Historical Society Collection.

Additionally, though Greenwich was increasingly home to millionaire bankers, railroad magnates and rich entrepreneurs, agriculture was still a way of making their huge estates pay for themselves through the production of butter, milk, eggs, smoked meats, fruits and vegetables. The household could be fed from the harvest, and any excess could be sold. Farming also promised fulfillment on other fronts; communing with nature was considered vital for psychological health, a way of counteracting the strain and corruption of city life. The desire to acquire the idyll of the European country villa has echoed throughout American aesthetic history and led to the building of massive pleasure gardens in the vein of Versailles and Schönbrunn – in Greenwich and elsewhere – gardens that decreased in size as land increased in value.

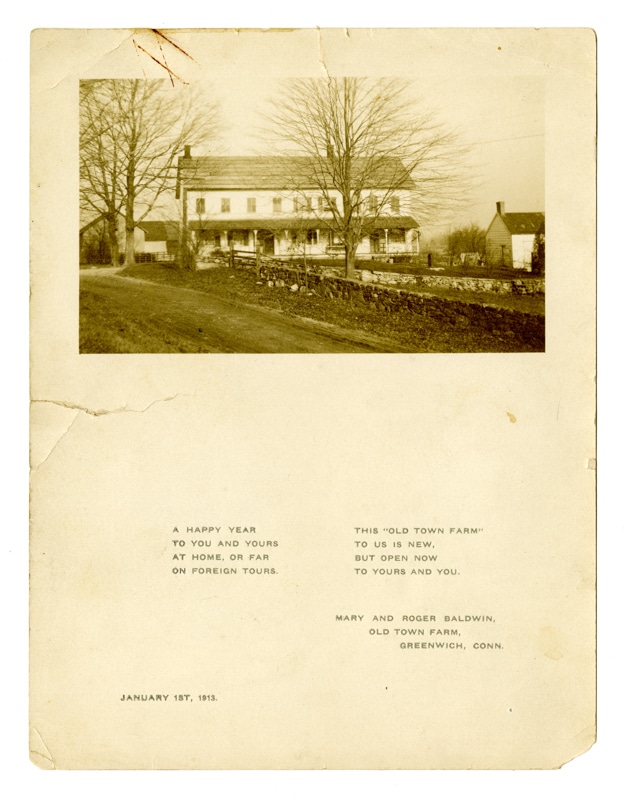

The Greenwich community also saw agriculture as a way of addressing social issues in both local and international contexts. For over a century the Old Town Farm housed town residents who had grown too old or sick to continue to support themselves, as well as those who were down on their luck and needed work. Though not many records of the Farm exist outside of comments in the local papers, it seems that the land was farmed by those who could not find work but were well enough for physical labor, and the produce was used to feed the tenants (called “inmates” by the newspapers). The Farm was maintained by the Town of Greenwich as a way of ensuring care for vulnerable populations. However, the original Town Farm was on 125 acres off of Round Hill Road, an extremely desirable piece of property, and in 1905 the Farm was sold at auction.

An edition of the Port Chester Record from the time reported that the proposal to “… authorize the selectmen to sell or lease the present poor farm and erect a proper building for the keeping and care of the town poor on land near the contagious hospital building” was met with staunch opposition, stating also that it was certainly a scheme by someone hoping to swoop in and steal the valuable property. That someone ended up coming from Port Chester: Congressman William Ryan purchased the property and built his home there. That the Old Town Farm was an operational farm is corroborated by the announcement that farming tools and cows were auctioned off from the estate shortly after the initial auction. Ryan would only hold onto the property for about six years before selling it to Roger Sherman Baldwin, and it would eventually be developed into Baldwin Farms. As with so many other properties, the rising land prices were simply too appealing to ignore, and the agrarian past fell by the wayside.

Around the time that Baldwin was building his manor house on the site of the Old Town Farm, the world was careening towards World War I. Thousands of young men across the country fell into step overseas, leaving behind the fields and crops they typically worked. To relieve the labor shortage, the Woman’s Land Army of America (WLAA) was formed in 1917, modeled on the British Women’s Land Army. Made up largely of college-educated young women known as farmerettes, the WLAA sent units out to farms to assist with the agricultural work that the soldiers had left behind. Nationwide, the farmerettes were received with mixed reactions. Some farmers wanted nothing to do with the organization, not believing that women could manage the hard labor. Other men viewed the organization with a paternal feeling, lauding the WLAA for giving women something to do and a way to feel useful, but not taking its efforts seriously.

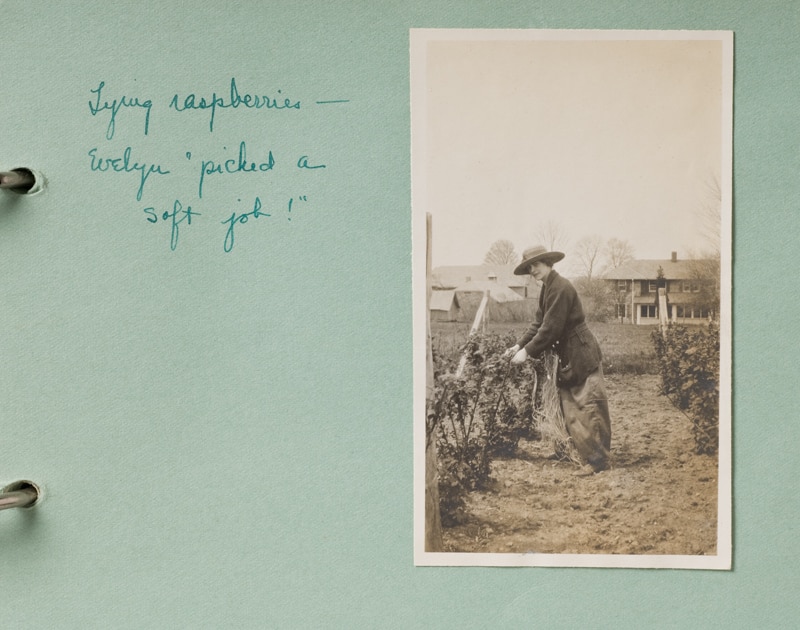

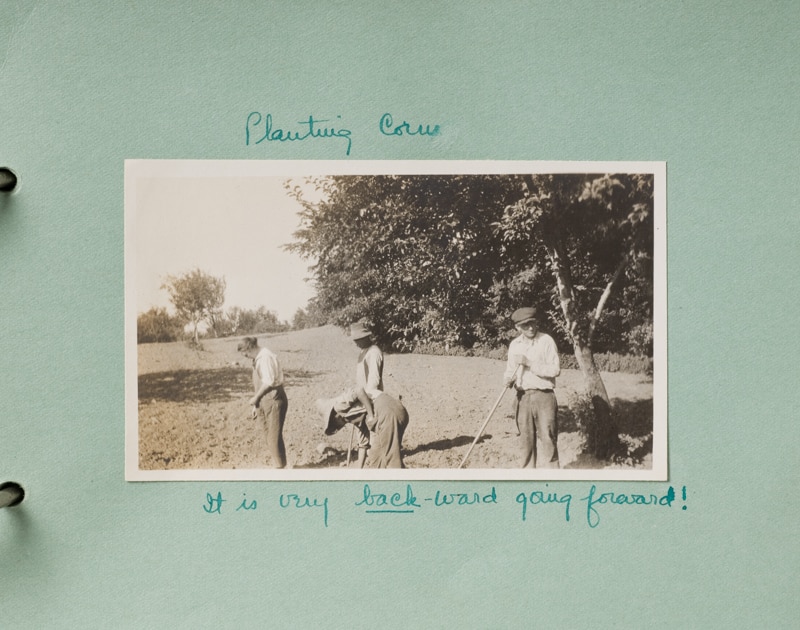

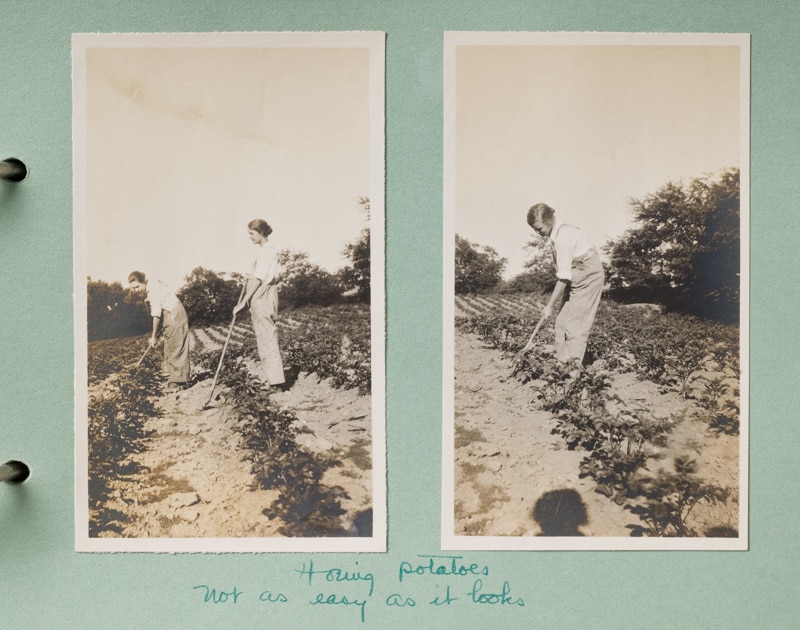

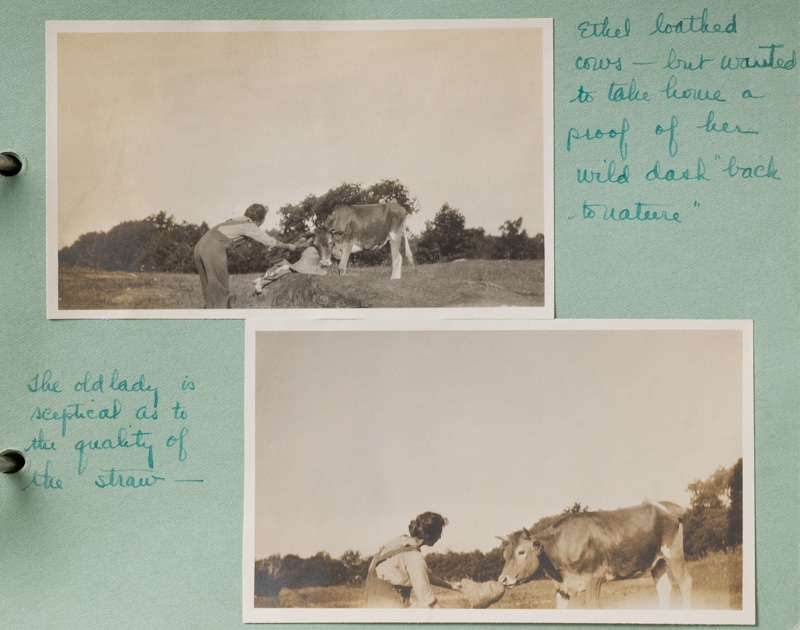

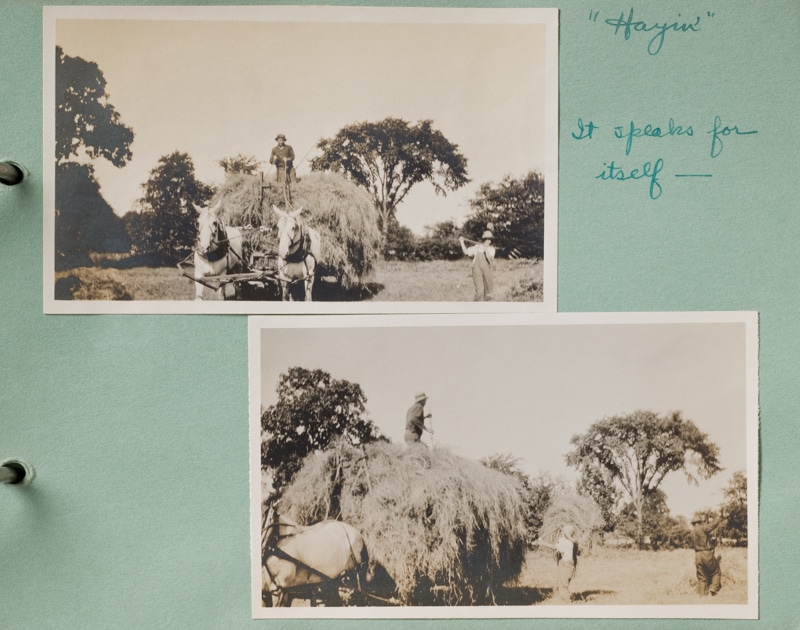

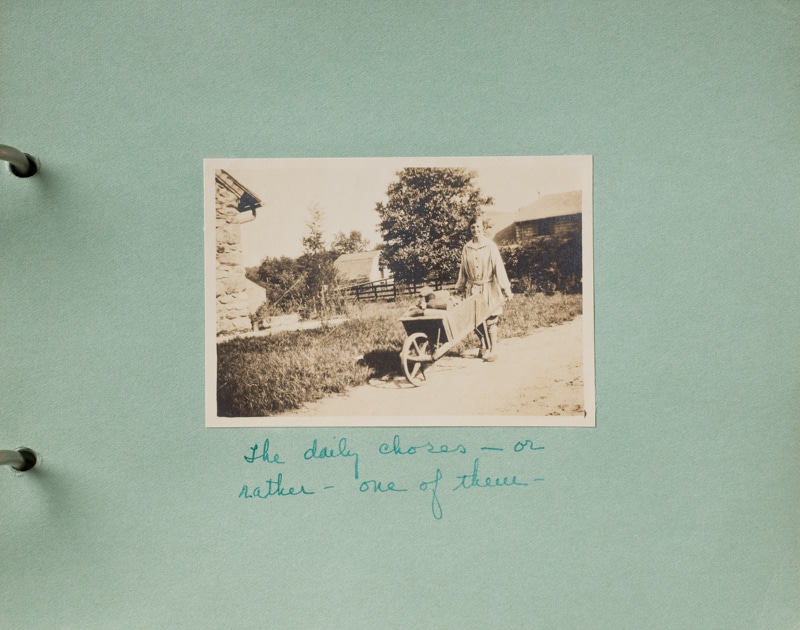

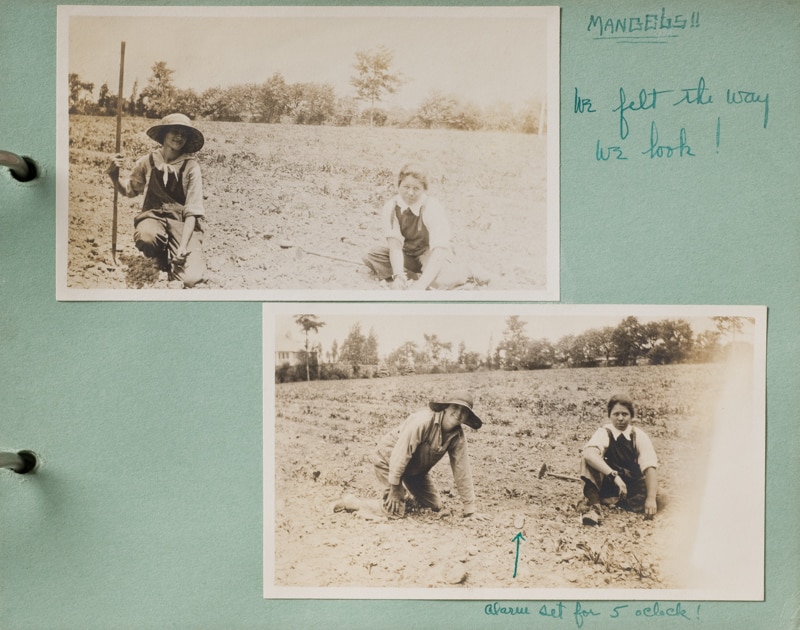

Greenwich’s Sabine Farm, the property of Henry J Fisher, became the home to a unit of farmerettes out of Wilton, Connecticut. The group began work on May 1, 1918, and over the course of the summer they tied raspberries, planted and cultivated corn, built a hutch for rabbits, hayed, weeded and harvested produce. They created an album of photos now in the Greenwich Historical Society’s collection, recording their summer of hard work in the dusty fields, pulling their cots out of their tents to sleep under the stars on summer nights, bonding with the Fisher family and the fulltime agricultural workers who remained in the States, and learning to care for the farm animals. The cheeky comments that accompany the photographs indicate how much the farmerettes enjoyed their summer, possibly the first opportunity many of the young women had to experience some degree of independence, and to test the strength of their bodies with physical labor. Though only reaching a membership of about 15,000 women at its height, the WLA helped to relieve local labor shortages – and by extension, food shortages – and served as an example for later mobilization schemes, like Rosie the Riveter during World War II.

For more information about the Women’s Land Army of America, visit this post from the Library of Congress.

The outline of Greenwich’s agricultural past is perhaps hard to see at times. Beyond ventures like Augustine’s Farm and community garden plots, it can seem like there is little to remind us of the fertile soil under our homes and businesses. But the agricultural history of Greenwich, beyond even the street names and famous properties, still survives in our collections and memories, in the parks and natural places that were once home to cows and crops.

Many of the images in this post have been recently digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). The Greenwich Historical Society’s Archival team is currently working on digitizing over 20,000 images across multiple collections, ensuring their preservation and accessibility for current and future Greenwich residents. This work is made possible by the IMLS grant.