Childe Hassam’s first trip to Greenwich, Connecticut probably took place in 1894 when he paid a visit to his friend, artist John Henry Twachtman, who purchased a house in the town in 1890. Through Twachtman, Hassam came to know the Holley family, and beginning in 1896 he made nearly annual trips to stay in their boardinghouse in the nearby village of Cos Cob, lodging there for weeks or sometimes months at a time. Often he was accompanied by his wife, Kathleen Maud Hassam.

For Hassam and many of the artists, art students, writers, journalists and other cultural luminaries who frequented Cos Cob in the summers around the turn of the twentieth century, the village was ideally located – a short ride by train from New York’s Grand Central Station, but a world apart from the busy urban landscape.

Painters were attracted to the coastal Connecticut village’s vernacular New England architecture, and many other New York visitors found welcome in the bohemian culture of the Holley House and its boarders. The aestheticized atmosphere of the Holley House, with its Japanese-inspired elegance combined with old New England furnishings and architecture, inspired a number of Hassam’s most famous paintings.

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH

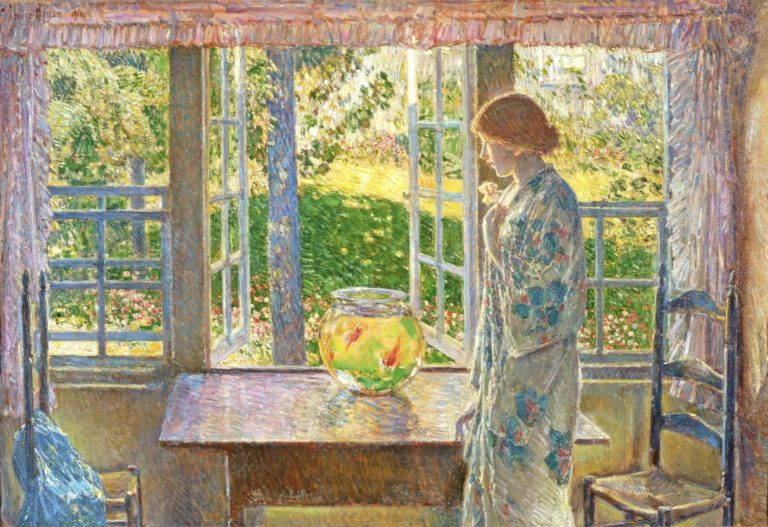

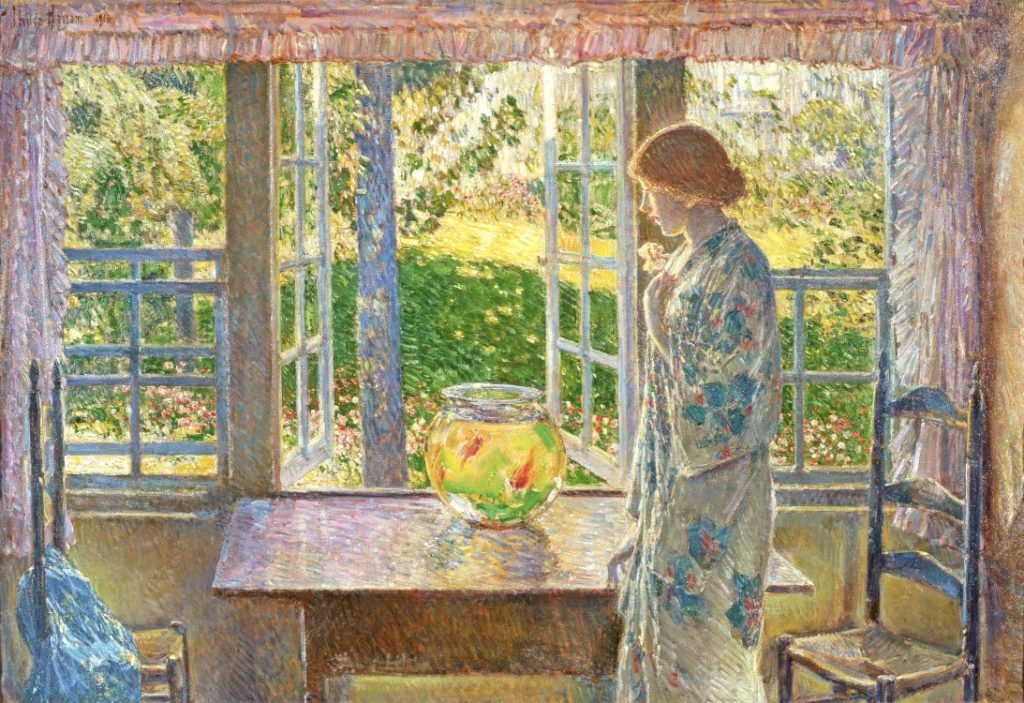

Painted in the Holley House, The Goldfish Window is one of Hassam’s celebrated “Window” series, featuring women, often in Japanese-style dress, gazing away from the viewer toward sunlit windows. Praised for their beauty and atmospheric charm, Hassam’s window paintings were among his most critically acclaimed and commercially successful work.

Greenwich Historical Society, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles M. Royce

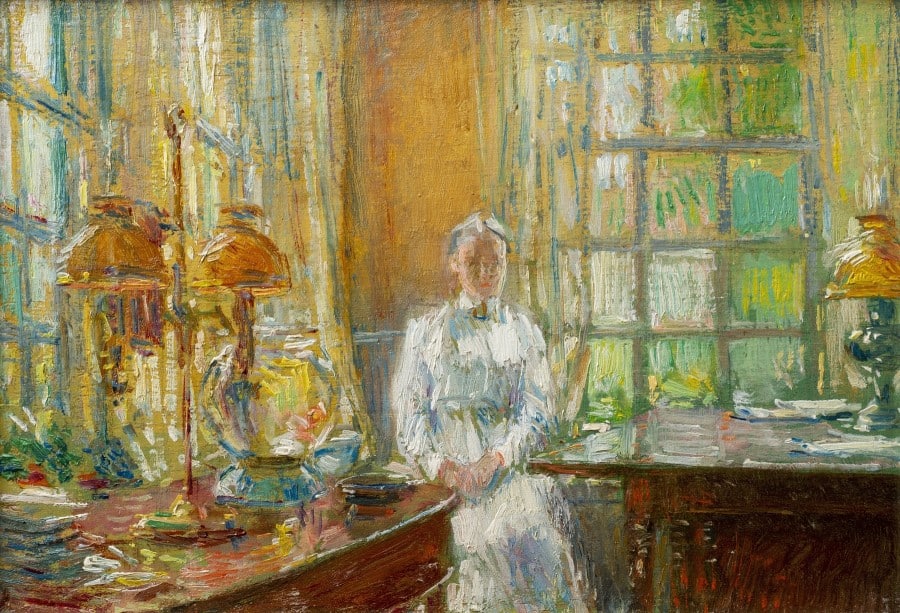

A small oil study on wood panel – one of several small paintings Hassam made in 1912, perhaps drawing inspiration from James McNeill Whistler’s diminutive “note” paintings, which Hassam admired on a visit to the collection of Charles Lang Freer – depicts Josephine Holley, proprietor of the Holley boardinghouse. Hassam’s tiny painting positions Mrs. Holley seated primly in a white dress, hands folded in her lap, in the corner of the boardinghouse’s dining room. To her right, perched on a table in the foreground, is a round goldfish bowl. A similar bowl featured prominently in Hassam’s 1916 painting The Goldfish Window.

Greenwich Historical Society, Photograph Collection

Photo credit: Peter Paige

Greenwich Historical Society, Museum Purchase with Donor Funds

In another small oil study from 1912, this one executed on the reverse of a cigar box lid, Hassam captures a woman standing in front of the prominent Federal fireplace surround in the Best Bedroom of the Holley House. The figure in the painting may be Hassam’s wife Maud; when boarding with the Holleys, Hassam and Maud often preferred to stay in this large well-appointed bedroom on the house’s first floor.

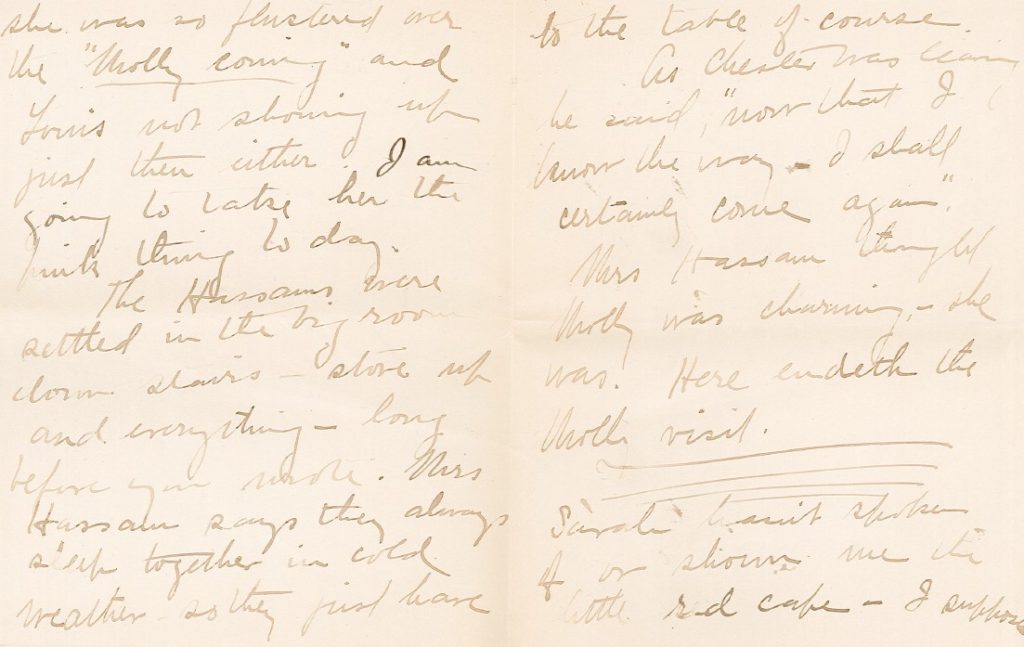

Greenwich Historical Society, Holley-MacRae Papers

Writing to her mother Josephine in October 1902, Constant Holley stated that “the Hassams are settled in the big room down stairs – stove up and everything…” She continues “Mrs. Hassam says they always sleep together in cold weather so they just have the big bed.”

Greenwich Historical Society, Holley-MacRae Papers

While the Holley family enjoyed a friendly relationship with the Hassams, they were not immune to his artistic celebrity. In another letter to her mother, Constant Holley MacRae could not help expressing her pride that the famed painter complimented her table setting for the Thanksgiving holiday, writing: “Mr. Hassam said it was the prettiest table decoration he had ever seen – Candleabrum [sic] in the center – the pine from that to the corners of the table and the silver candlesticks on the ends. We had a jolly time.”

Maggie Dimock is Curator of Exhibitions and Collections at the Greenwich Historical Society

Lost Landscape Revealed: Childe Hassam and The Red Mill, Cos Cob is on view at the Greenwich Historical Society January 16-March 28, 2021.

Find more information about visiting and and reserving timed tickets.

Presented by First Republic Bank