If you’ve ever come across a deed from the eighteenth or even nineteenth century, you’ve probably been confused by the language used more than once. Are we sure this is English, and how can I get any usable information from this document? This post will break down a deed from top to bottom, defining terms and giving a brief explanation of how a reader might find the information they need.

Real Property versus Personal Property: At its most basic, real property is real estate. Land, houses or structures, and fixtures. It may include other complexities, like mineral rights, oil drilling rights, airspace rights, or easements to name a few. However, the majority of early American deeds don’t include these kinds of complexities outside of something often called the Widow’s Third. Even as far back as 1792, the surviving widow of a deceased man was entitled to ⅓ of the husband’s estate if he died without leaving a will. We have examples in our collection of deeds specifically delineating what third of the house the widow would have access to, up to and including specific rooms and ensuring access to the water pump and the kitchen.

For more information about the history of marriage laws in Connecticut, view this report from the Office of Legislative Research.

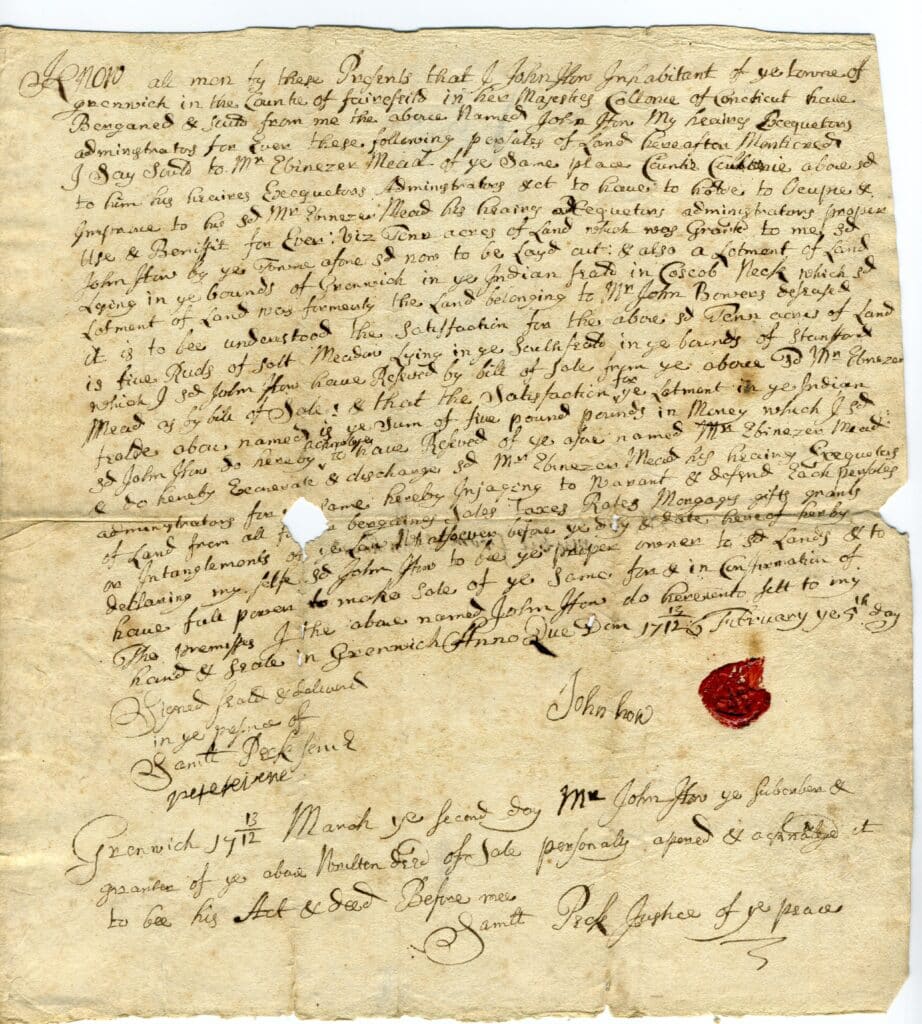

Real property deeds will open with a generally long and confusingly written paragraph. Even printed deeds, where the parties involved fill in the blank spaces, can use confusing language.

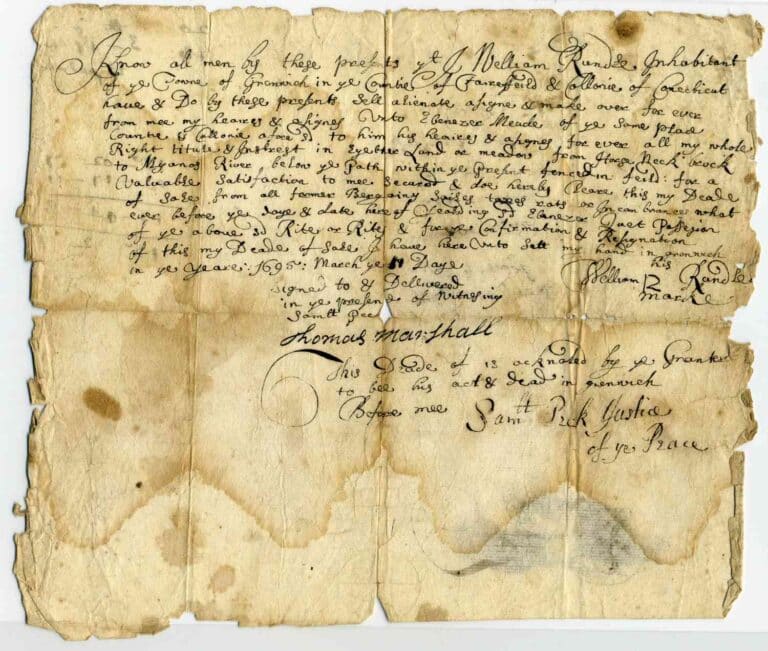

Who is Selling or Gifting This Property: The first sentence of any given deed introduces the person or persons selling or gifting the property first by name, then by town, county, and state. “Know Ye That I Silas H Mead, of Greenwich in the County of Fairfield, Connecticut” tells you that the property is being sold by Silas H. Mead, and that he lives in Greenwich, Connecticut. This does not mean that the property is necessarily being sold in Greenwich though, or even in Connecticut, as many families did have real estate investments in New York and even occasionally up in Massachusetts or out to Ohio.

Considerations: After the introductory sentence, comes the statement of considerations. While in modern contract law you will often see the phrase “good and valuable considerations” as almost a throwaway necessity of phrasing, the deeds that a reader might be interacting with using this guide are often written during the period in which this phrasing and language was being laid out into American law, and therefore you may see someone giving property away for “good considerations” or “valuable considerations” instead of both “good and valuable considerations.”

- Good Considerations are generally founded on emotional reasons: love, generosity, and close relationships. A parent might give their child a deed to a piece of property out of good consideration without any valuable consideration.

- Valuable Considerations are generally founded on financial reasons, rather than emotional: money, trade of property, but also marriage. An individual might sell a piece of property to another individual for valuable consideration without any good consideration.

- Good and Valuable Considerations, therefore, refer to a combination of both emotional and financial reasons for moving property.

This book, written by Joseph Chitty and first published in 1826, is a treatise on contracts that details different types of considerations.

Who is Buying or Receiving This Property: The individual buying or being given the property is named twice in quick succession. First, stating that the considerations were given to the seller from the buyer, and then explicitly stating that the individual selling the property does “give, grant, bargain, sell and confirm unto” the named individual the property that will be described.

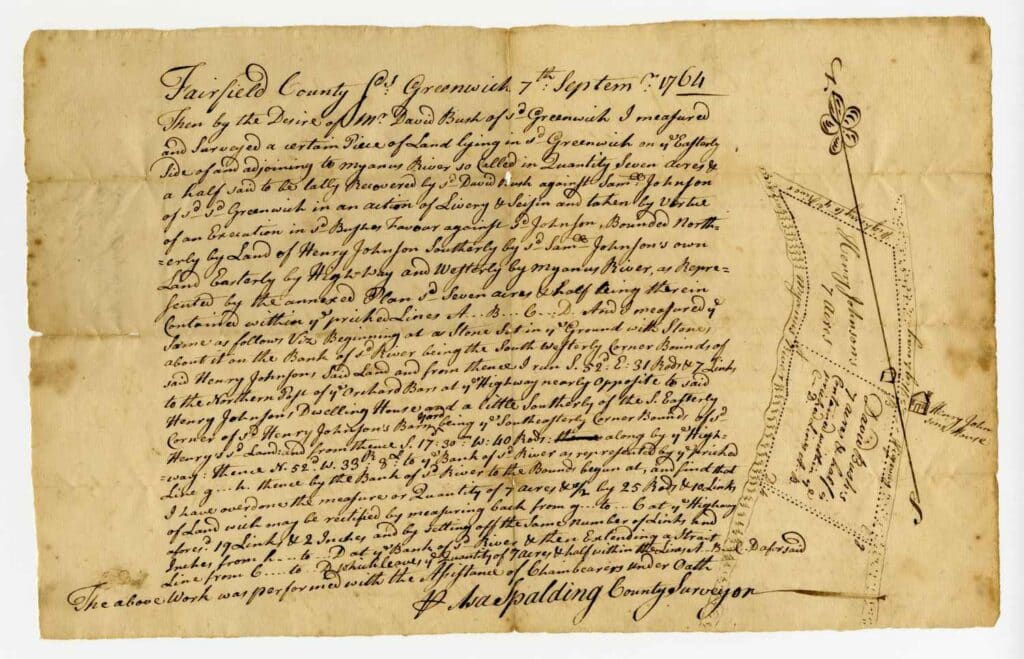

Description of Property: This is where most readers will begin to have trouble. Property deeds from this time period tend to include strange descriptions not only of the size of the property, but where said property is located. These property descriptions will open with a sentence describing at its most basic where the land being sold is located. It can be as broad as “the North of Greenwich” or as specific as “within Cos Cob.” The deed will then describe the size of the parcel of land in question.

Some measurements you might see include:

Acre: An acre is a measurement of area. It was originally defined as the area of land that a lone farmer could plow with a team of oxen in one day. It’s been standardized to 4,840 square yards, but was originally defined as being one furlong long, and four rods wide.6

Rood: A rood is a measurement of area equal to one quarter of an acre.

Rod: A rod is a measurement of length, standardized at 16.5 feet.

Chain: A chain is a measurement of length, standardized to 4 rods.

Furlong: A furlong is a measurement of length or distance, standardized as one eighth of a mile, ten chains, or forty rods.

All definitions are sourced from the Oxford English Dictionary.

Once the size of the parcel of land has been defined, it will then set out the boundaries of this land. Now, a reader might hope that having this clearly defined set of boundaries might be helpful in terms of being able to find said land, but sadly this is not the case. The boundary definitions can be vague, and in modern terms impossible to locate. “Three rods North from the old apple tree” is not helpful when said apple tree was cut down over a hundred years ago. Deeds will also often say simply “bordered East by my own land” or “bordered North by land of Silas D. Mead” relying on information that is simply not available to a reader in the 21st century. Even descriptors like “main road” or “the Mianus river” are only so helpful in narrowing down to a still very large area for where the land might have been situated. Ultimately, if the reader is looking to try and determine where an old piece of property was located, merely having the old deed for said property is unlikely to be enough.

Almost finished: Once the property has been described, the seller will once again name the buyer and themselves, making sure to state that the property as described is not under the jurisdiction of the seller’s heirs, assigns, executors, administrators, etc. It is at this point that the deed would be brought before the Justice of the Peace, signed, and then a copy of said deed would be filed with the state.

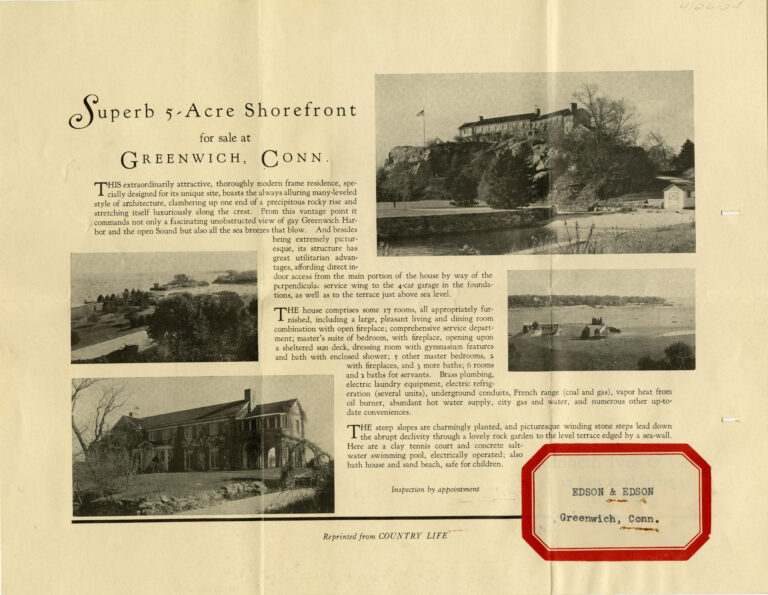

That’s it! You’ve managed to get through your Early American real property deed! We have a large collection of deeds here at the Greenwich Historical Society archive, and you can call or email to make an appointment if you’d like to view any of them. October is American Archives Month, and we’ll be highlighting our collections and the work our archival team does every day. Join us all month long to learn more about how the Greenwich Historical Society Archives make your history accessible to you! Follow us on social media and share your archives stories using the hashtag #ArchivesMonth.

Some items featured in this post were part of collections processed as part of a three-year grant-funded project from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). The Greenwich Historical Society’s Archival team is currently working on digitizing over 20,000 images across multiple collections, ensuring their preservation and accessibility for current and future Greenwich residents. A backlog of unprocessed collections is also being organized and described to make them accessible to patrons and researchers. This work is made possible by the IMLS Museums for America grant.