Community gardens have existed for as long as communities have. On the North American continent, many indigenous First Nations held and worked land communally. Several eastern nations, such as the Haudenosaunee and Lenape peoples, considered women to be the workers and keepers of the land, a belief which undergirded their matriarchal cultures. In Europe, feudal societies had communal plots that generated the food supply for the serfs themselves, smaller than the fields they worked to produce the crops owed to the lord of the manor. When Europeans were first colonizing New England, farming collectively was often the only chance of survival, given the lack of laborers and experience, and even these endeavors would have likely failed if it weren’t for the help of indigenous neighbors. This is, generally, the story of the first communal gardens in Greenwich, but throughout its history Greenwich residents would continue to come together to plant and harvest with an eye to the common good.

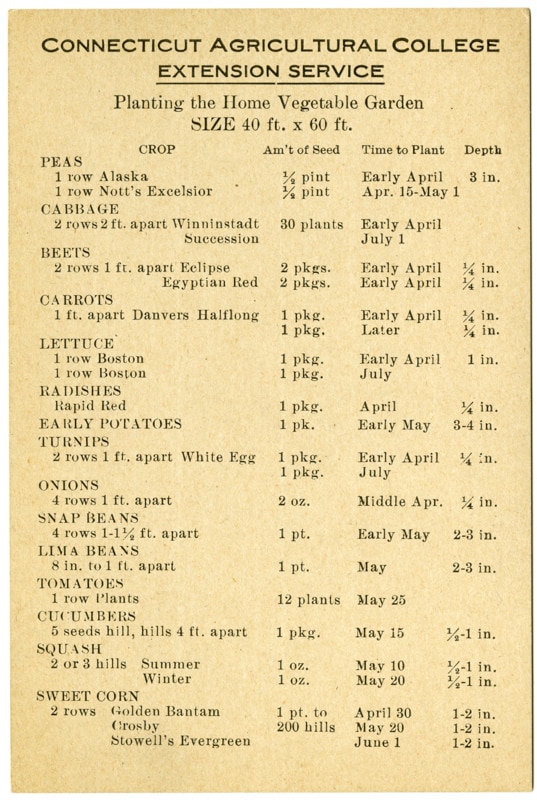

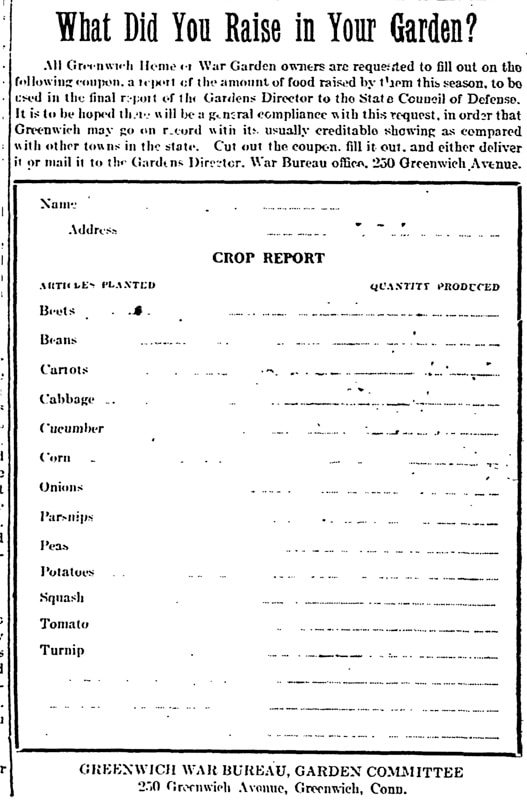

Greenwich continued to be a farming community up until the first few decades of the 20th century, with many estates maintaining kitchen gardens even as they transformed their farms into pleasure grounds. These kitchen gardens were expanded rapidly with the advent of World War I. The War Gardens of 1917‒1918 were started in response to the worry that the food supply would fail due to destruction overseas and the loss of farm laborers as men went to the trenches. Private land was repurposed to grow fruits and vegetables, some of which were processed by the Greenwich Canning Kitchen to be sent to the front lines, and land on the outskirts of town was offered up to community members who wanted to contribute to the cause but didn’t have the space. The local newspapers ran encouraging articles and letters from readers, including one titled “Keep a Toad” that exhorted gardeners to keep the “patriot” who was working to defend the plants from bugs, and another titled “Raise Sheep on Lawns,” which insisted that Greenwich residents didn’t have to tear up their beautiful lawns to produce food, but should instead keep a flock of sheep to trim the grass and provide meat for the kitchen.

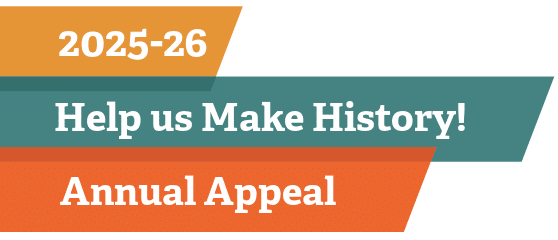

This donor list and introduction come from a report on the mission and productivity of the Greenwich Canning Kitchen. The report highlights the comparative costs and benefits of the operation, and thanks the donors for their patriotism. It is interesting to note that all but two of the donors were women, although they are referred to by their husbands’ names. Greenwich Historical Society Collection.

View more information about the History of Agriculture in Greenwich

Collective gardening and preserving became a patriotic duty, strengthening the ties of the community and inspiring amazing ingenuity and sacrifice. Dr. Oliver Huckel, the pastor at the Second Congregational Church, recalled both the difficulties and triumphs in a speech at the 1932 annual meeting:

“The trying times of the World War … with their strenuous patriotic undertakings and self-sacrificing economies for ‘conservation’; their war parades, war garden parties, patriotic mass meetings, drives for funds; sewing, knitting and gossip parties; ‘giving until it hurt’; installment plan purchases of Liberty Bonds; eating gutta percha biscuit and plaster-of-paris pancakes lubricated with oleomargarine so the real stuff might be sent to the soldiers, who finally didn’t get much of it—and all that; how well we remember it all!”

– Daily News-Graphic, December 10, 1932, “Dr. Huckel’s Story of Seventeen Years’ Changes”

Even as Dr. Huckel gave his speech, the community was being tested again by the Great Depression, and would be tested further with the coming of World War II.

The stock market crash of 1929 had catastrophic effects for the entire nation. Millions became unemployed and homeless, roving the country looking for work and shelter. Bread and soup lines were common in urban areas, and families everywhere tightened economies to try to hold onto their homes and livelihoods. The residents of Greenwich, possibly inspired by the successes of their War Gardens, banded together to feed their community. Overseen by a town committee and assisted by the Westchester-Fairfield Horticultural Society, more than 20 estates grew vegetables in their gardens to be distributed to those in town who were having trouble making ends meet. Other estates loaned acres of their land to applicants who planted and worked the plots using town-provided seed and then shared out the resulting harvest. Local Boy Scout Troop 15 also contributed: the troop started their own garden at 118 Pemberwick Road to grow vegetables to be distributed by the Byram Parent-Teachers’ Association to families in need of financial support. Commonly grown produce included cabbages, tomatoes, carrots, beets and eggplants.

The Clark Williams estate, known as Live Oak (above) and Wilshire Farms were two of the large estates that contributed land to the Depression-era Gardens. Their garden managers were C. Wilburn and Mr. Mair, respectively. Greenwich Historical Society Collection.

After World War II, the country turned slightly inward with the explosion of the suburbs and the rise of the private family home. Community gardens wouldn’t gain another surge in popularity in Greenwich until the 1960s. The Armstrong Court Community Garden was started in 1963 with instruction from local garden clubs, primarily Hortulus. The Armstrong Court plots served the tenants of the Armstrong Court Housing Association project, and though interest had ebbed and flowed, a few residents were still gardening there decades later when the garden was refurbished. Since the revitalization in 2009, when volunteers and local students helped to cut back overgrown brush, pick up litter and clean up the stream that runs along the garden, it has experienced an upsurge in popularity. Greenwich Community Gardens, the organization that oversees the gardens, has expanded to include the Bible Street Gardens in Cos Cob, and plans and manages volunteers in the Nathaniel Witherell Garden, which grows produce for the residents’ meals.

From the early days to our modern times, Greenwich community members have sought to serve and connect through gardening. These communal places have seen the town through some of the most difficult periods of American history, feeding body and soul through good food and community spirit. The burgeoning of the local and organic food movements has reminded us, more than ever, that we are what we eat, but the continuing legacy of community gardens reminds us that the people who join us at our plots and tables are just as important.