In the Library & Archives, we have the privilege to work with and care for the materials that make up our collective history. Archivists organize, inventory, describe, digitize, and maintain vast collections with hundreds of thousands of individual pieces that can include anything from photographs to deeds to VHS tapes to ledgers. All of this careful work is done to make archival holdings as accessible as possible, so that members of our community might find what they need. We accompany researchers on their journeys into the past, through the wows and ahas of a successful search, and the crestfallen disappointment of documents and details lost to time. All of this work is done in the full knowledge that the archive will also survive as a record of our mistakes: the misidentified landmarks, the misread names, and the misremembered dates, all hopefully corrected over time with the help of our community.

As accessibility is increased through digitization and the expansion of online archives, we face the constant decision of what should be included in these far-reaching resources. This decision can be especially difficult when it comes to deciding whether to scan the reverse or back side of objects and images. For some objects, the choice is straightforward; the cribbage board in the Greenwich Historical Society’s collection might seem like any other cribbage board – until you turn it over and read the plaque declaring it made by President Grover Cleveland and owned by Greenwich resident E. C. Benedict. The reverse side of that object is integral to comprehending its meaning and value.

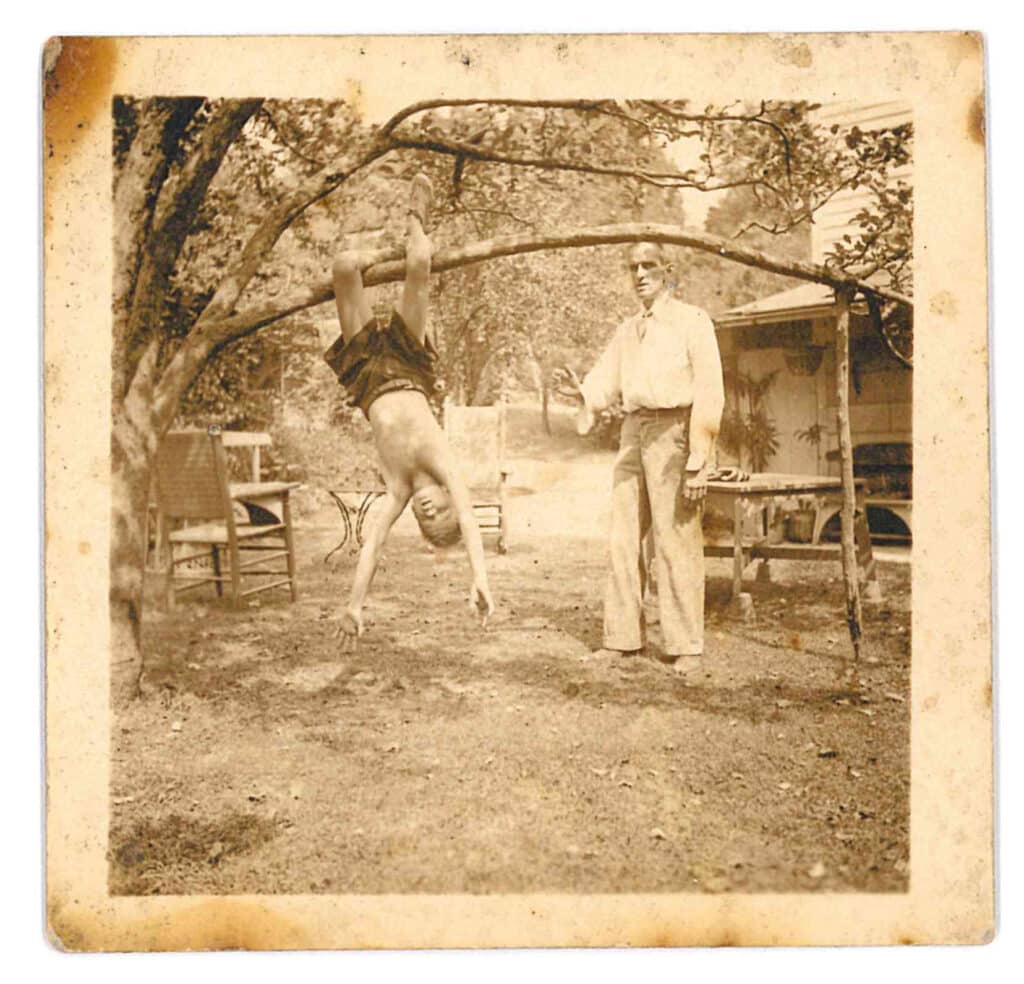

But the sentimental note on the back of a photograph? The goofy messages on the envelopes of letters? These items are less clear-cut. Most every historical or humanities focused institution has a collections policy outlining the objects and history it aims to preserve, and every institution has only so many resources to achieve those aims. Every day, archivists do the very best they can, and some things still fall through the cracks. The following images are examples of materials in the Greenwich Historical Society’s collection, the fronts of which have been scanned and inventoried, but the backs of which were not scanned until this post.

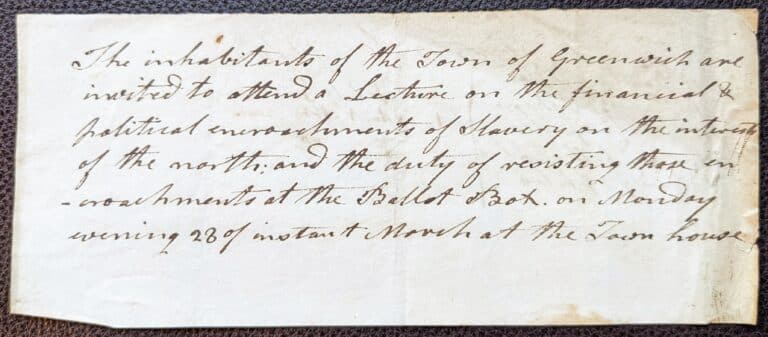

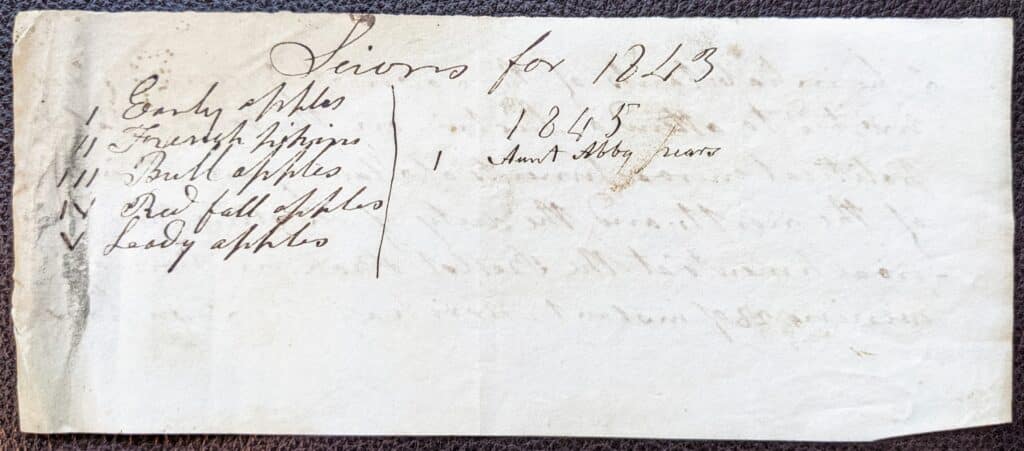

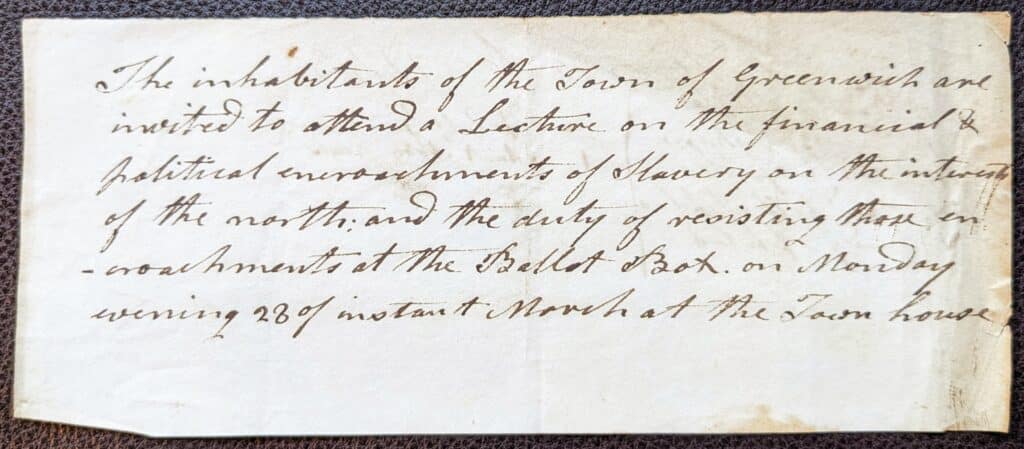

The first is one of the most recent re-discoveries in the Greenwich Historical Society Archive. When Project Archivist Ashley Aberg was processing the Mead collection as part of the Historical Society’s ongoing IMLS grant, she came across a scrap of paper that recorded a list of apple varieties in 1843 (and one variety of pear in 1845). While this record does tell us interesting things about what was being planted in the area in the middle of the 19th century, the reverse of the document is more historically significant: it records the details of a meeting to discuss the political and financial ramifications of the abolition of slavery before an upcoming election.

One can assume that a member of the Mead family received the note as an invitation to attend the meeting, to either make his opinions known or to be persuaded by others. This was a common method of communicating town meetings and election dates, before newspapers were widely printed and distributed. We have no way of knowing if the Mead recipient attended the meeting or not; the fact that he kept the piece of paper doesn’t necessarily indicate his intention of going to the meeting. It would have likely had more to do with the value of paper at the time, which is further evidenced by its re-use for the apple list. It also tells us that prior to 1843, people in Greenwich were getting together to talk about the idea of abolition. They were particularly interested in abolition and slavery in relation to how those institutions might encroach on the political and financial rights of the North.

This message is a local remnant of common abolition arguments from the period right before the Civil War. Many Northerners argued for the abolition of slavery because they felt it threatened their political autonomy. As the borders of the United States expanded, there was a fear that, if slavery expanded into those new territories, the legislative interests of the Northern states would become overshadowed in Congress by those of the slave-holding states. Abolition, rather than always being rooted in a sense of equality and the right to liberty, was often a politically calculated argument during this time period. This record in the Greenwich Historical Society Archives is evidence of that.

For more information about abolition, visit the Library of Congress’s online exhibition “Abolition, Anti-Slavery Movements, and the Rise of the Sectional Controversy”

To learn more about slavery in the North, check out this book from Greenwich Library.

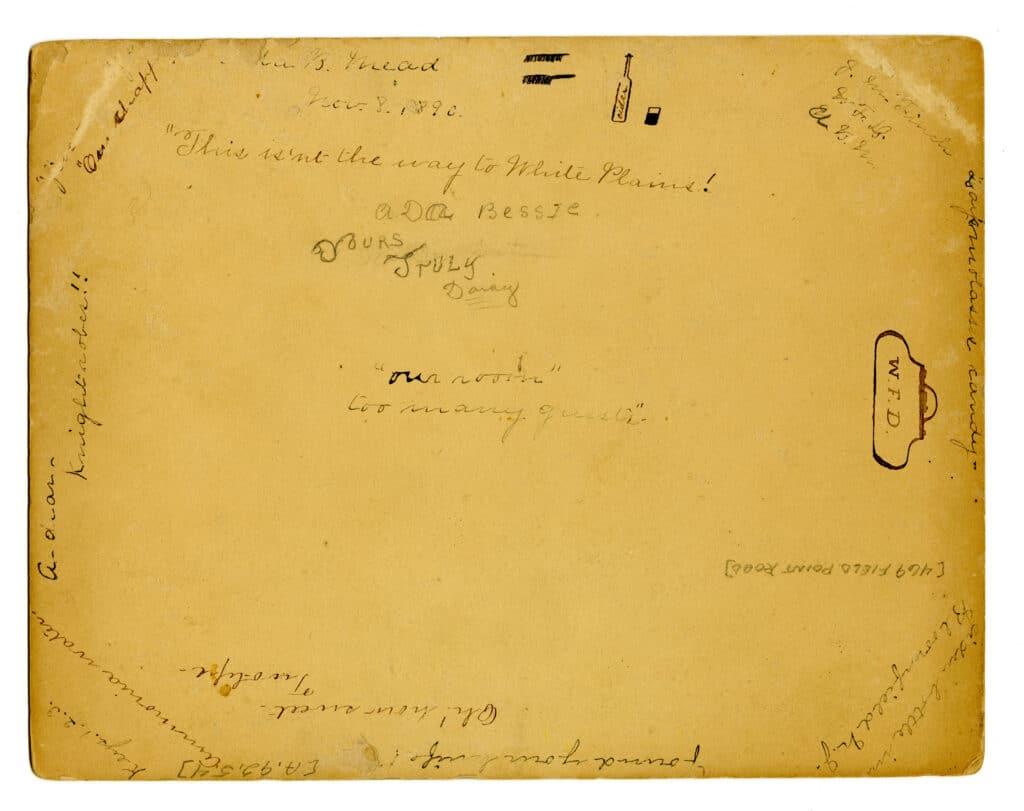

Given the long history of great estates in Greenwich it probably isn’t surprising that a large portion of the holdings of the Greenwich Historical Society Library & Archives are dedicated to real estate – grand lists, real estate company records, photographs and postcards of houses, and architectural drawings, to name just a few collections. The front of this photograph from the Nelson B Mead Collection shows a house located at 469 Field Point Road with its distinctive stone porte cochere. Field Point Road was one of the earliest roads built in what is now known as Belle Haven, a promontory that was part of the Mead family holdings for generations. The land was purchased in 1884 by the Belle Haven Land Company, who built the roads and developed the subdivision of Belle Haven. The house with the stone porte cochere must have been one of the earliest completed, given the photo’s date of November 8, 1890. All of this can be discovered from studying the image of that distinctive architectural feature and other readily available real estate records, but the back of the photograph holds a whole other world of information.

Almost nothing is known for sure about these inscriptions. They appear to be a record of a visit in small notes, like a photo album contained in a single picture. The references to White Plains and Bloomfield, New Jersey may provide evidence that this photograph was a souvenir from a trip. Perhaps the house on Field Point Road was only a stopover on a much larger journey, or perhaps it was home base for a summer of smaller road trips. The tiny handwritten inscriptions are tantalizing: What is Day’s molasses candy? Who lost their knife? Why was there ammonia water around?

This isn’t the way to White Plains!

These details and stories likely died with their creators. The back is also signed by an unknown “Daisy” and Ada Bessie Mead, a daughter of Silas Merwin and Elethea Mead. While it’s possible that Daisy was the author and illustrator of the inscriptions, some of them do appear to be written by different hands and in different inks. Possibly everyone on the trip contributed, and it was given to little Ada Bessie as a keepsake; she would have only been about 11 years old in 1890. Whether we ever discover their meaning or not, these notes preserve a humor and enthusiasm that aren’t frequently present in the more stoic portrait and landscape photographs of the time. They remind us that these historic figures were people, children, too.

Our work as archivists can sometimes be made more difficult in the digital age. Objects from a particular time and place, which are often part of larger collections, are free to be viewed in isolation on digital catalogues, without the benefit of context or physical connection. Like everything else, the materials in historical societies are products of their times, and without the proper context they can be misconstrued and even harmful. Try as archivists might to add complete descriptions, subject tags, place names, and related content, we can never fully contextualize or control the afterlife of a digital record that is sent out into the World Wide Web. Not only are there not enough forms and fields in the digital world to contain the vast history locked up in a single object, but archivists must also work within their own limited time and funding.

The archival materials examined above are not grand documents. They aren’t manifestos, or land deeds, or court decisions. They can certainly be easily overlooked. But they are also testaments to the lives and ideas of the people who came before us, who walked and joked and voted on the same ground that we do today. The archives are ultimately about making connections and finding this common ground. Digitization has allowed us to make ever broader connections, to see how people from so many different places share a history of joy and tragedy, of inside jokes and moral imperatives. Just remember to check the back.

October is American Archives Month, and we’ll be highlighting our collections and the work our archival team does every day. Join us all month long to learn more about how the Greenwich Historical Society Archives make your history accessible to you! Follow us on social media and share your archives stories using the hashtag #ArchivesMonth.

Some items featured in this post were part of collections processed as part of a three-year grant-funded project from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). The Greenwich Historical Society’s Archival team is currently working on digitizing over 20,000 images across multiple collections, ensuring their preservation and accessibility for current and future Greenwich residents. A backlog of unprocessed collections is also being organized and described to make them accessible to patrons and researchers. This work is made possible by the IMLS Museums for America grant.