In early 2020 the Greenwich Historical Society received a generous grant from the Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation for the Arts in support of John Henry Twachtman Online. This resource, which has also received support from the Lunder Foundation and the Cross Family Charitable Fund, will soon be available on greenwichhistory.org.

Twachtman Online will present comprehensive information on the work of John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902), a major figure in late nineteenth-century American art. Twachtman lived in Greenwich in the 1890s and established the Cos Cob art colony that continued into the 20th century. In preparation by Lisa N. Peters, Ph.D. for over twenty-five years, Twachtman Online will be an important contribution to American art scholarship.

As a preview of the content available in Twachtman Online, we are pleased to present the following essay on the painting Old Holley House, Cos Cob, from the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum. The essay was prepared by Dr. Peters in consultation with Susan G. Larkin, Ph.D., author of The Cos Cob Art Colony: Impressionists on the Connecticut Shore (Yale University Press, 2001) with contributions from archives and curatorial staff at the Greenwich Historical Society.

Maggie Dimock, Curator of Exhibitions and Collections, Greenwich Historical Society

Cincinnati Art Museum, John J. Emery Fund.

Run by Josephine and Edward Payson Holley from 1882 through 1900, and subsequently by their daughter Constant Holley MacRae, the Holley House was the base for the summer art classes taught by Twachtman in the 1890s, often along with his close friend Julian Alden Weir (1852–1919). The Holley House was also Twachtman’s intermittent residence after he and his family vacated their home on Round Hill Road in Greenwich in December 1899 through the spring 1902.

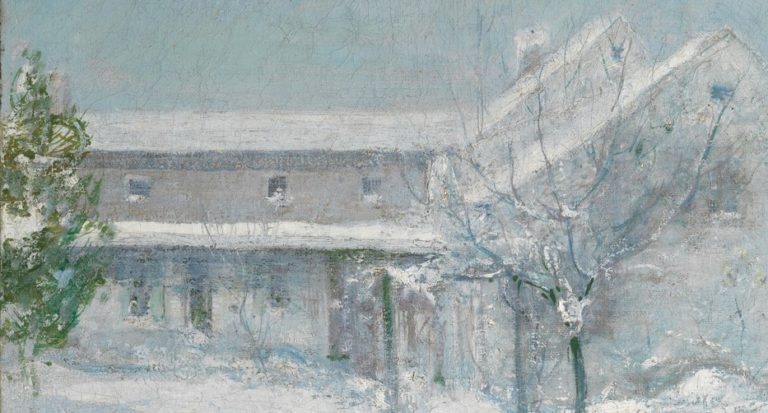

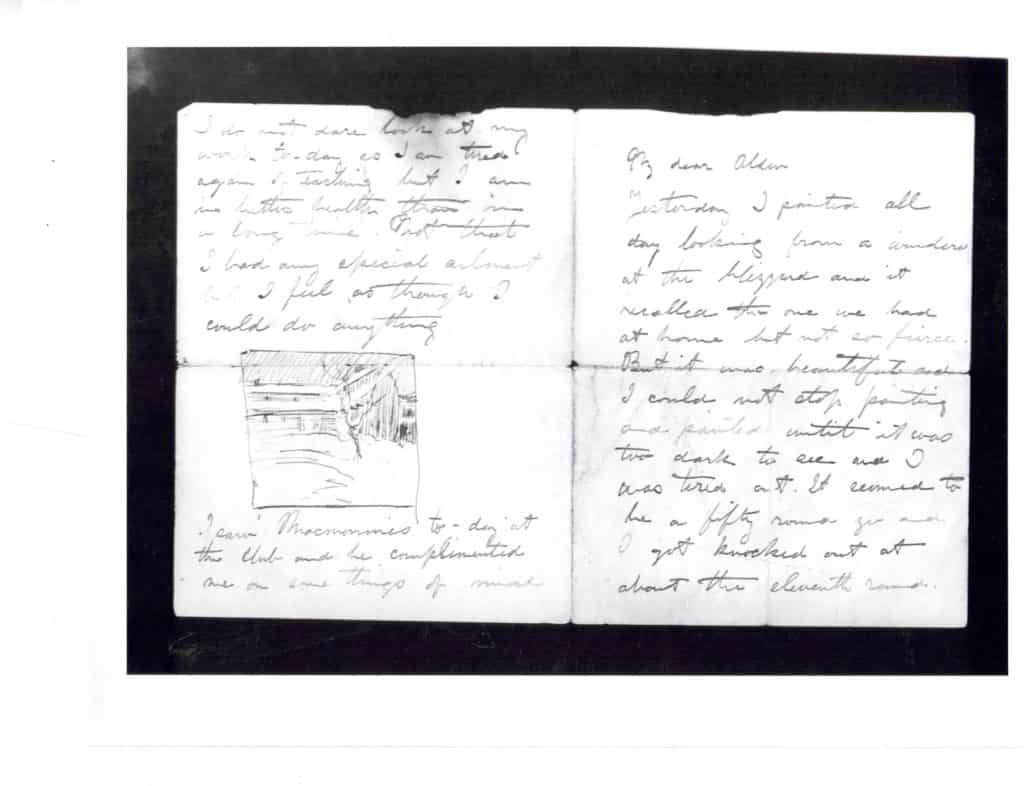

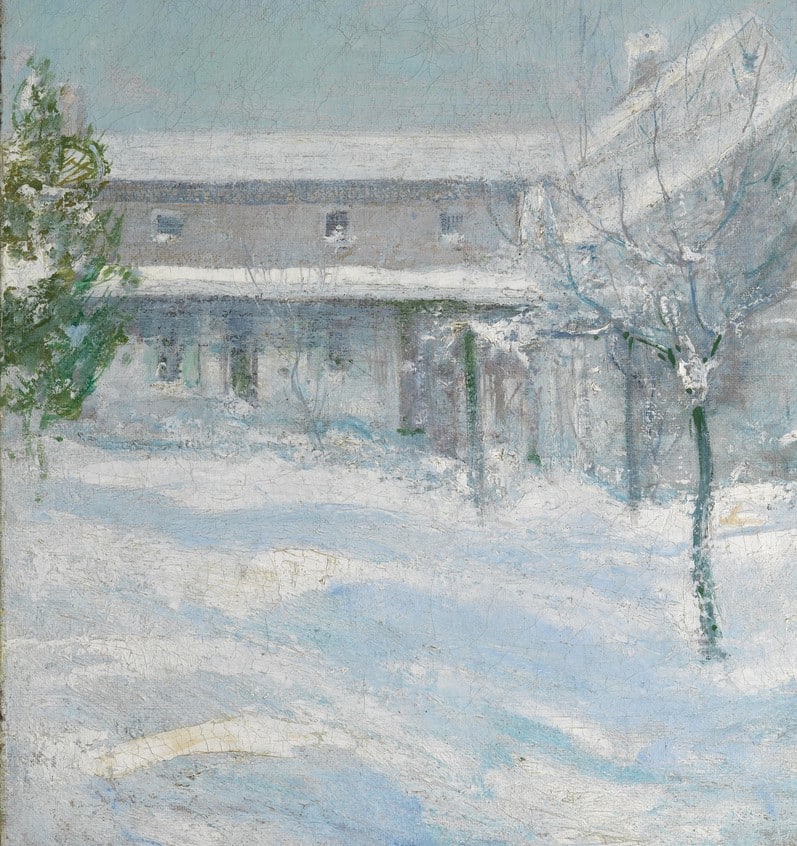

Depicting the house amidst a snow-covered landscape, Old Holley House, Cos Cob (fig. 1) seems at first a midwinter scene. However, an undated letter Twachtman sent to his son John Alden Twachtman indicates that it was rendered in mid-March 1901 (a time when Alden was studying art in Paris). In the letter Twachtman drew a sketch of the painting (fig. 2) and stated:

Yesterday I painted all day looking from a window at the blizzard …. it was beautiful and I could not stop painting and painted until it was too dark to see and I was tired out. It seemed to be a fifty round go and I got knocked out at about the eleventh round. [1]

He went on to comment: “I saw Macmonnies to-day at the club and he complimented me on some things of mine he saw at Durand Ruels.”

ca. March 1901 (pages 1–2). Private collection.

The club to which Twachtman refers is The Players Club on Gramercy Park in New York City. From the letter’s contents, it is clear that Twachtman wrote it between March 4 and March 16, 1901, when a solo show of his work was on view at New York’s Durand-Ruel Gallery. There, as Twachtman indicates, it was visited by the artist Frederick MacMonnies (1863–1937), a member of the club and a friend—as was Twachtman—of the architect Stanford White (1853–1906). In fact, an article in the Port Chester Journal describes a heavy snowstorm that arrived suddenly in Greenwich on the afternoon of March 14. [2] It seems likely that the painting was the product of that very day and storm.

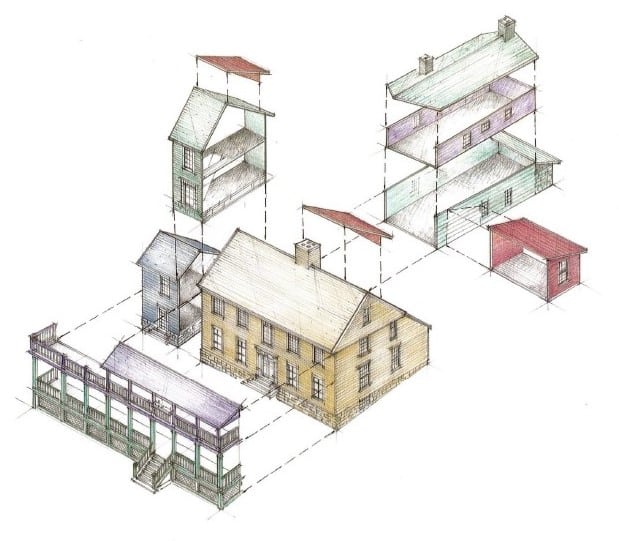

In the painting, Twachtman depicted the southern and rear wing of the Holley House rather than its better-known east-facing front façade (fig. 3), where two large porches overlooked the Lower Landing on Cos Cob’s small harbor. The window from which he observed the scene appears to have been on the second floor of a barn or stable that once stood to the northwest of Toby’s Tavern (which served as a “Railroad Hotel” in the era of the Cos Cob colony, and was returned to its late-nineteenth-century appearance during the reimagining of the Greenwich Historical Society’s museum-campus in 2018). [3] The structure from which Twachtman painted is no longer extant, having been demolished sometime after 1935, but its appearance is today mirrored in the footprint and orientation of the Library & Archives and Permanent Collection wing of the Historical Society’s museum building. [4]

Viewed from the south, the house is an irregular structure, revealing its separate parts that were added over time. [5] However, as a contemporary photograph taken from Twachtman’s angle demonstrates (fig. 4), his view gave the house an appearance of unity and solidity, which he captured in his painting by rendering it monumentally within a square-shaped arrangement, parallel to the picture plane. [6] In the painting, the section visible at the right consists of the south wing of the house (its earliest part, built 1728–33), which extended outward 15–20 feet. Behind it is the southern gable end of the main house (constructed 1730–33). Through foreshortening Twachtman revealed that these two parts seemed close together from his vantage point and he observed how the chimney at the center of the main house appeared to be at its far end (at the right).

The section of the house at the left is its west (rear) wing, added sometime between 1755 and 1771 as a back kitchen. Its second story was likely used as a slave quarters by David Bush (1733-1797) and his son Justus Luke Bush (1777-1844), who operated a tide mill on Cos Cob’s Lower Landing. [7] The west wing’s façade is two-toned, with white planks on the ground floor and rusticated siding on the second floor. On a day when snow softened the atmosphere, Twachtman recorded this distinction subtly by using tints of blue (on the ground floor) and red (on the second floor).

One factor in the painting may clarify a date in the house chronology: a dormer thought to have been built onto the west roof of the south wing by 1901 is not visible in the painting. [8] Therefore, it is possible to conclude the dormer must have been constructed after March of that year. Twachtman featured another aspect of the setting in the form of a pergola situated outside the door to the western addition (figs. 5–6). It was covered with leafy vines in the warmer months, which Twachtman acknowledged by painting it in green pigment. At the left, an evergreen tree obscures a chimney at the far west end of the house (visible in Twachtman’s sketch of the painting). In the painting, Twachtman used the tree to bracket the house within the composition.

Greenwich Historical Society, Photograph Collection.

Twachtman painted snow with a specificity unmatched by other American artists of his time. Throughout his career, he took delight in how snow changed a scene’s appearance. Here, using firm strokes of white paint, he recorded the way that the snow gathering on the two gables at the right continued downward into the parallel horizontals of the west wing’s roof and awning. Across the façade, he recorded the rhythmic pattern of the windows that appear darkened against the blizzard-filled air. Studying the snow closely, he observed that it was higher than the base of the house and had been blown in drifts against its walls. In the foreground, he applied sweeping strokes of buttery pigment and may have used a palette knife to capture the wetness and density of a typical spring snow. Across the painting’s surface are the blue shadows, characteristic of Impressionism, and for which Twachtman was renowned—in 1932, the New York Times art critic Edward Alden Jewell called Twachtman “the first American artist to see and paint blue shadows.” [9]

A second tree is even more prominent in the work: the young tree in the middle distance on which new leaves have begun to sprout (fig. 7). Susan G. Larkin interprets the slender sapling as “a metaphor of youth in contrast with the aged building, whose arboreal emblem might be the evergreen that cushions its strong horizontals.” She writes: “Snow suggests the winter of life, the end of a cycle. For Twachtman, the old house inspires introspection on time and change.” [10]

The near tree was also a means by which Twachtman created depth in the scene, establishing a midpoint between his vantage point and the house. Before him, snow covered the ground in deep, unbroken waves, making it seem that traveling across it would be difficult despite the near proximity of the house. Seeing the house, where he was an insider accustomed to its warmth and comfort, from the perspective of a detached observer, enabled Twachtman to express his heightened appreciation of the stability it offered him. This was especially important to him at a time when his family was away in France. At the Holley House, he found refuge from the stress he experienced during his days in New York City. There, while teaching art at the Art Students League and Cooper Union, he longed to be back in Cos Cob, away from the noise and grit of the city, in a place where he felt at home and could paint. On January 2, 1902, he wrote to Josephine Holley from The Players Club, stating:

The town is using me up. I am on the go from morning until night and nothing doing. Always busy about some damned unnecessary thing and spending money to beat the band and to no purpose. And I also miss the painting.

No doubt referring to celebrations on the first day of the new century, he continued:

Yesterday they tried to blow the city into the sea and I wish they had and then I could row ashore and go back to Cos Cob. [11]

There, he wished that “Joe” would bring him his “pitcher of water” and wake him at “ten in the morning.”

In the painting, Twachtman gives recognition to the way that something that seems close can feel distant, providing the opportunity to see it in a new way. The relativity of closeness and distance is a recurring theme in Twachtman’s art, and one that is relevant to our close-distancing today.

Further Observations

Another look at Twachtman’s sketch of his painting in his letter to his son raises some thought-provoking questions about his painting process (fig. 8). It seems likely that Twachtman sent the sketch to his son before he had finished the painting. This can be seen in the differences between the two images. In the sketch, the tree at the left that obscured a chimney at the west wing’s far end is not present. Additionally, Twachtman appears to have modified the foreground tree, making it more upright than in the sketch, to balance it against the horizontal west wing. Finally, he may have cropped the work at the right, as the drawing reveals a broader view of the landscape. While he painted directly watching a blizzard, he met his compositional and expressive aims at a later time.

Lisa N. Peters, Ph.D. is an art historian specializing in late nineteenth-century American art. Among many publications, she is the author of John Henry Twachtman: An American Impressionist (High Museum of Art, 1999).

Notes

[1] Letter, John Henry Twachtman to John Alden Twachtman, ca. March 1901, private collection.

[2] “They started for Banksville,” Port Chester Journal, March 21, 1901, p. 4. The article describes members and friends of the Hope Council No. 9, Daughters of America, who left Port Chester, New York, on Thursday, March 14, to pay a visit to the Victory Council, No. 15, located in Banksville, New York, which extends over the Connecticut border into Greenwich. When the group set out, the “sun shone brightly.” The article stated: “from the Toll Gate through Greenwich, the roads were in fair condition,” but from then it began to rain heavily. The group obtained permission to wait out the rain at the hall at Stanwich, in northern Greenwich, from where they intended to return home long before midnight. However, as noted in the article, “it started to snow quite hard, and before the time arrived to depart for home the ground was covered with nearly four inches of snow. The group returned at 2:00 a.m., reaching Port Chester at 4:30 a.m.

[3] Constructed probably in 1805 as a two-story modified saltbox and expanded in 1855 into an Italianate three-story “Railroad House” hotel, Toby’s Tavern has now been restored, with an exterior that matches its 1855–1935 appearance. An analysis of the site in preparation for its restoration can be found in David Scott Parker, Architects, “Historic Structures Report and Feasibility Study” (unpublished manuscript, 2013).

[4] Parker 2013, pp. 82–83.

[5] In 2000, architectural historian James Sexton, Ph.D. produced a comprehensive study of the house, in which he determined the inaccuracy of earlier ideas about the structure’s evolution. James Sexton, “Bush-Holley House, Cos Cob, Connecticut: A Historic Structure Report” (unpublished manuscript, Greenwich Historical Society Library & Archives, 2000). Sexton’s research was the basis in 2015 for a continued study of the property, for its further preservation: David Scott Parker, “Findings & Suggestions: Based on the Bush-Holley House Historic American Buildings Survey Conducted December 2014–February 2015” (unpublished manuscript, 2015).

[6] Twachtman’s viewpoint is the result of a recent analysis by Greenwich Historical Society Curator Maggie Dimock, of historical material and the site itself.

[7] Sexton 2000 indicates that it was probably between 1848 and 1882 that the roof of this section of the house was raised and three windows facing south were added.

[8] Sexton 2000 (p. 39) describes and documents the addition in 1901 of this dormer to a bedroom in the second story of the south wing of the house. The dormer can be seen in a view of the rear in Childe Hassam’s Back of the Old House, 1916 (watercolor over sketch in brown chalk, 15 1/8 x 21 3/4 inches, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven), reproduced in Susan G. Larkin, The Cos Cob Art Colony: Impressionists on the Connecticut Shore (New York: National Academy of Design in association with Yale University Press, 2001), p. 113.

[9] Edward Alden Jewell, “Art: Qualified Impressionism,” New York Times, January 20, 1932, p. 16.

[10] Larkin 2001, p. 130.

[11] Letter, John Henry Twachtman to Josephine Holley, January 2, 1902, Greenwich Historical Society, Holley-MacRae Papers.