We are lucky here at the Greenwich Historical Society to be the benefactors of the many local history lovers who entrust us with their artifacts. As collectors and stewards of Greenwich history, we see the full gamut of historical objects. The extraordinary and the mundane – from a handwritten letter by Arthur Conan Doyle to an Electrolux vacuum – all arrive at our door. These items are hand-delivered by family members, sent to us in the mail, and occasionally left on our doorstep (please don’t do this – we need every bit of information about the object we can get!). Every generous donor, and every treasured donation, comes to us with a story. Recently, the Historical Society acquired a new story, one that came to us in the shape of a hand-stitched, 6 x 10 foot American flag with 42 stars, donated by the family of John Duff.

To learn more about why American flags are called “Old Glory” visit this blog post from the Smithsonian.

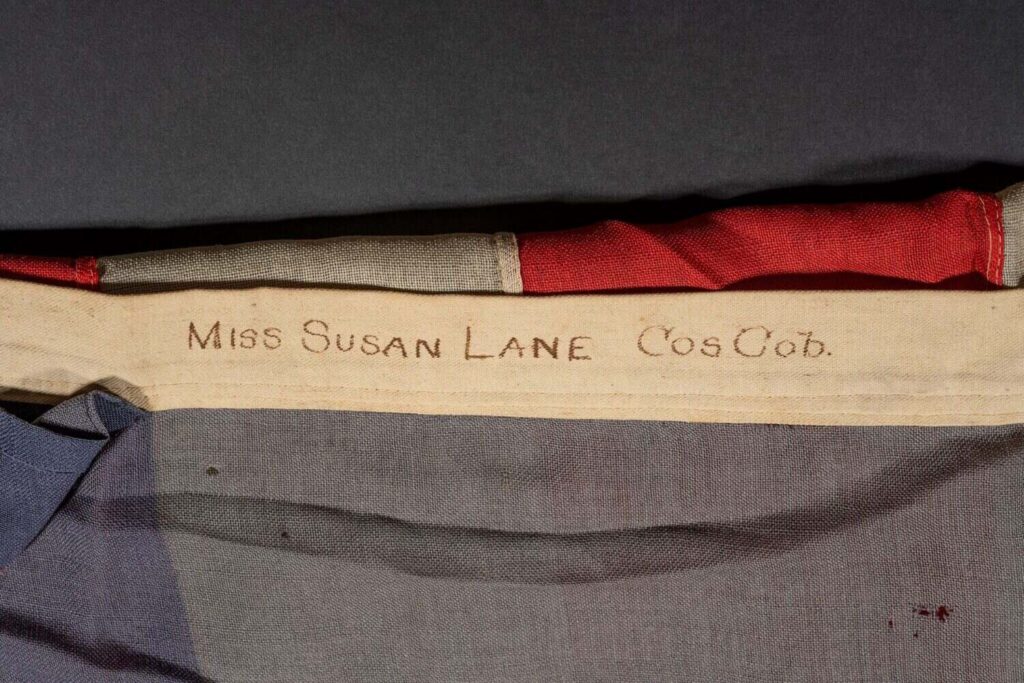

Two cousins descended from John Duff discovered an old flag folded up in a trunk, and after some investigations of their own they brought it to the Historical Society. To give an idea of the flag itself, it appears to be made out of a heavy, coarse linen material, and the seams show that both hand and machine stitching were used in its construction. Along the binding, where the flag would have been attached to a pole, is the inscription “Miss Susan Lane Cos Cob” written in black marker, as well as an embroidered “L.” The 42 stars are hand-stitched onto both sides of what is called the Union, or the large swath of blue on the American flag. Overall, the flag is in very good condition, with minimal staining, fading, or tears – suggesting that it spent a lot of its time folded up, or hanging inside somewhere, rather than outside, where it would have been exposed to the elements.

The 42-star flag is a rarity: it only accurately reflected the number of states in the Union from November of 1889 to July of 1890 – after Washington, Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota legally became states and before Idaho was admitted. However, because flags only become official on July 4 (a tradition started in 1818), and Idaho was added to the Union on July 3, 1890, (which was star 43), the 42-star flag was never an official banner of the United States. Despite its unofficial status, both at-home and commercial textile manufacturers wanted to stay ahead of the curve and celebrate the growing United States, which lead to the fabrication of these not-quite American flags.

To learn more about the history of American flags, visit PBS here.

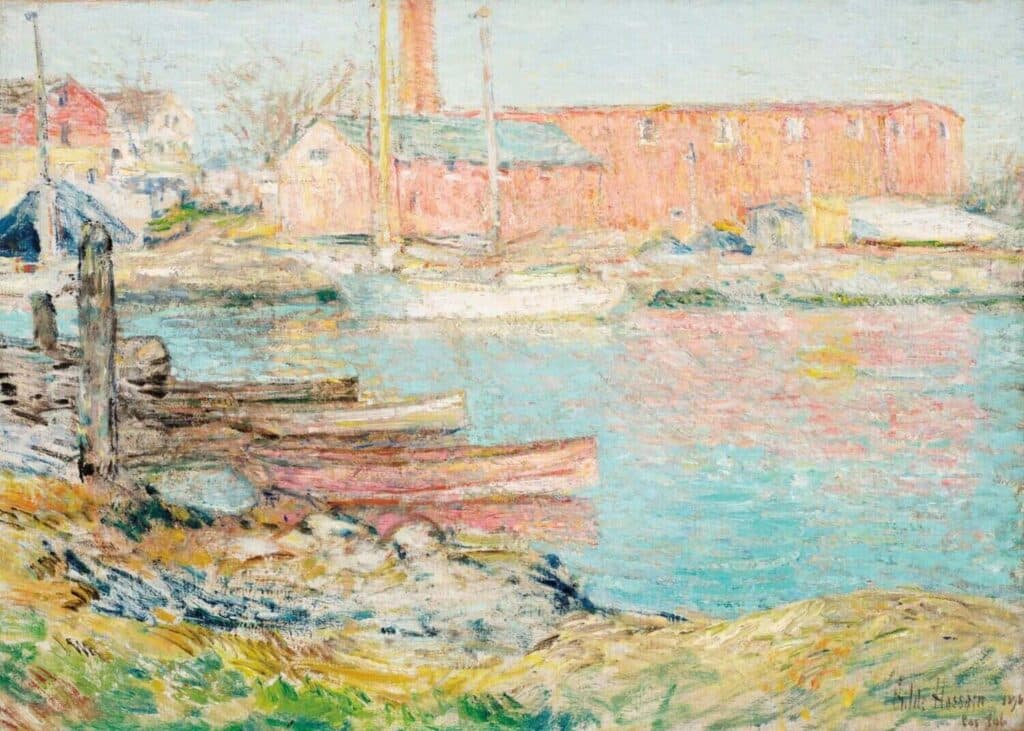

The Duff family members suggested that the flag may have come to their family through John Duff, who lived on the Lower Landing in Cos Cob. You might recognize the name John Duff, particularly if you were able to visit the exhibition of Childe Hassam’s The Red Mill, a painting acquired and exhibited by the Historical Society in 2020. Hassam’s painting shows the industrial area across the pond from Bush-Holley House, which was home to the Palmer & Duff Shipyard, a prosperous business that was an essential part of life on the harbor.

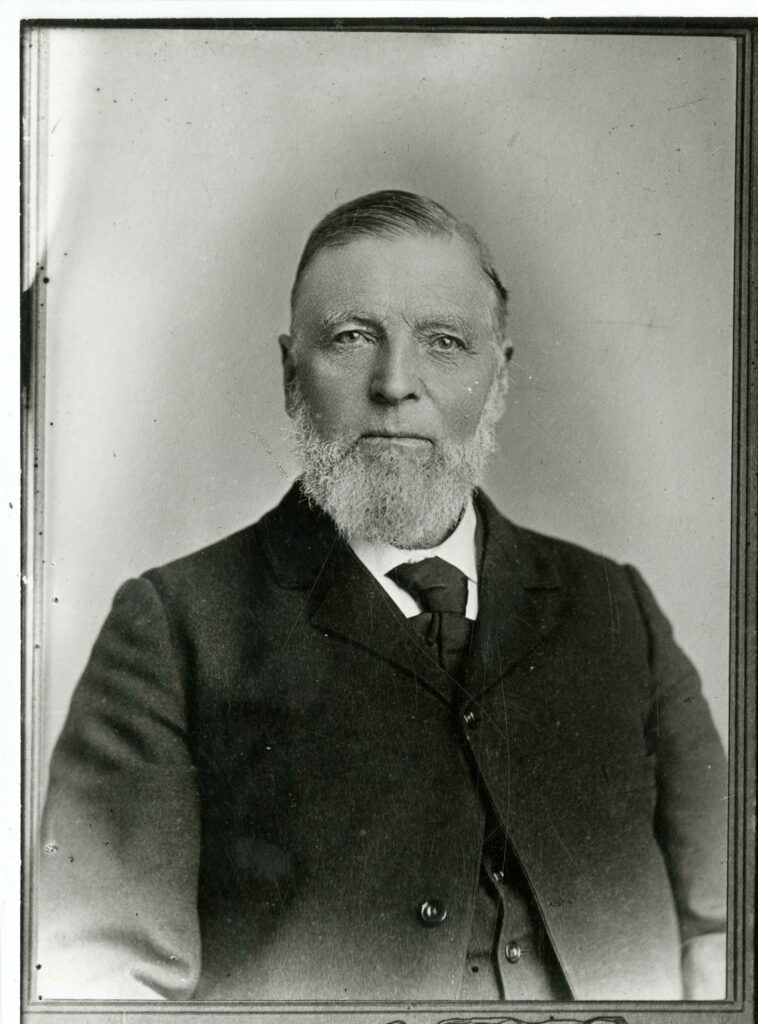

John Duff was born on September 22, 1824 in New York City. He purchased the property that would eventually become the shipyard in 1848, the same year that the first railroad came through the town of Greenwich. Denom Palmer joined Duff as his business partner in 1855, which is when the company became known as Palmer & Duff. The two men were lifelong friends and brothers-in-law, each celebrating the other’s achievements and joining in family gatherings and celebrations. Their work primarily consisted of repairing and building sailing vessels, and Duff is listed in multiple census records as a ship builder or ship carpenter. This was dangerous work, and local newspapers reported on Duff’s various injuries due to accidents, like falling from schooners or being hit with coal buckets, well into his 60s.

The Palmer & Duff Shipyard shut down in 1907 once the owners finally felt they were too old to keep at it; at the time, Palmer and Duff were 88 and 83, respectively. In addition to his successful business, Duff was also a well-known local character. He raised a family in Cos Cob with his wife, Deborah Ann Palmer (Denom Palmer’s sister), and they had nine children together. From the newspaper accounts, John Duff appears to have been well-liked, but we still couldn’t figure out how his family end up with a flag labeled clearly, “Susan Lane.” While the Duff donors had thoroughly researched their ancestor John Duff, Susan Lane was also a mystery to them. We turned to census and newspaper records from the turn of the century, and began piecing the story together.

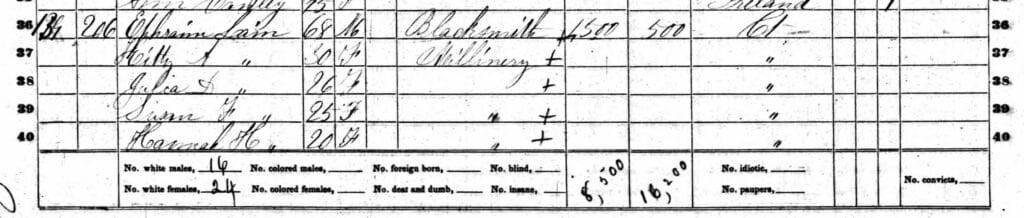

Susan Lane was born February 22, 1836 right here in Cos Cob. Susan’s father, Ephraim Lane, owned the house at 34 Strickland Road, which is still standing and plaqued today. Susan was born into a large family, although we can’t be certain of exactly how many siblings she had, given the lack of specificity in census records from the time. We do know that she was particularly close to two of her older sisters, Kitty Ann and Julia Drake, whom she lived with into her old age. All three women never married, and supported themselves well into their 80s as milliners in Cos Cob. Milliners were tradespeople, often women, who made their living by constructing and selling women’s hats. The intricate design and stitching required for such work would have well prepared any of the sisters to make the flag. They also may have learned their craft from their mother or another female relative, who could have made and then passed the flag down to Susan. This would explain the embroidered “L” in the top corner of the flag, which predates the later, marker-written label.

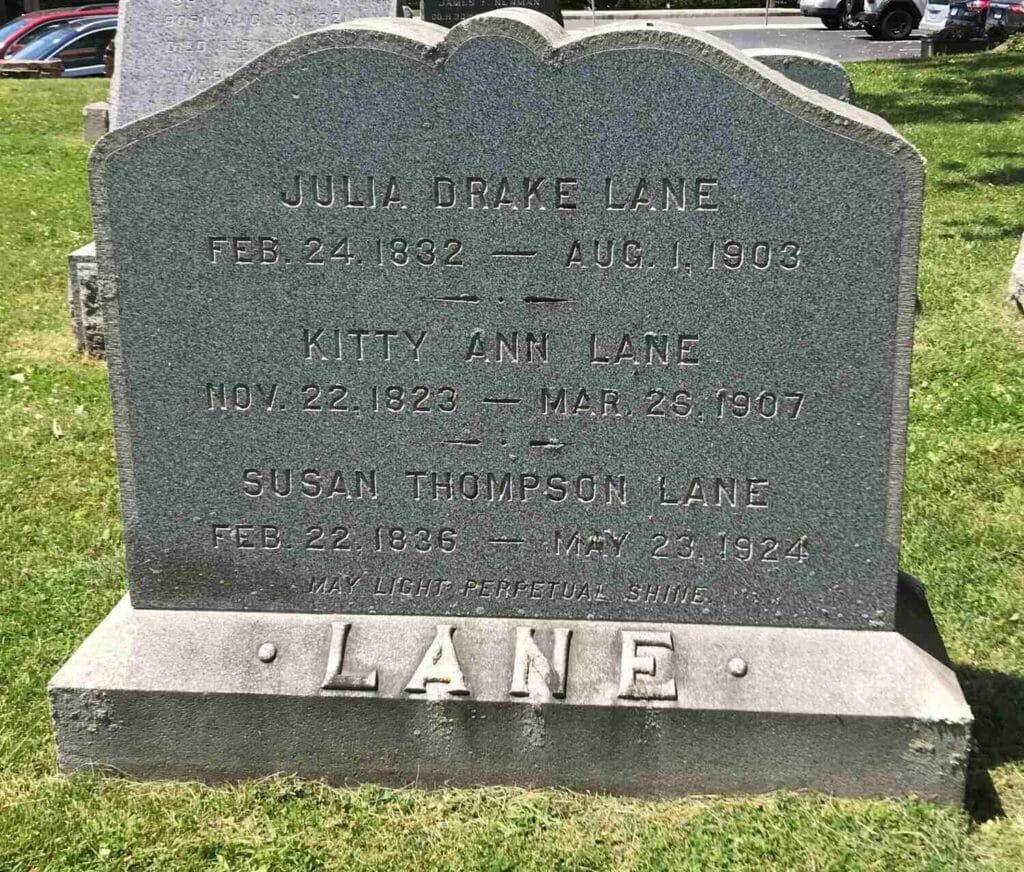

In fact, the Lane women were quite savvy about how they passed down their estates. In their wills, both Kitty and Julia stipulated their different bequests, which were only to be distributed after all three sisters passed away. This would have ensured that the surviving sisters would have the benefit of the estate of the whole household while they were still alive, supporting each other after death as they had done in life. The three Lane sisters are buried together beneath one headstone in the Second Congregational Church Cemetery.

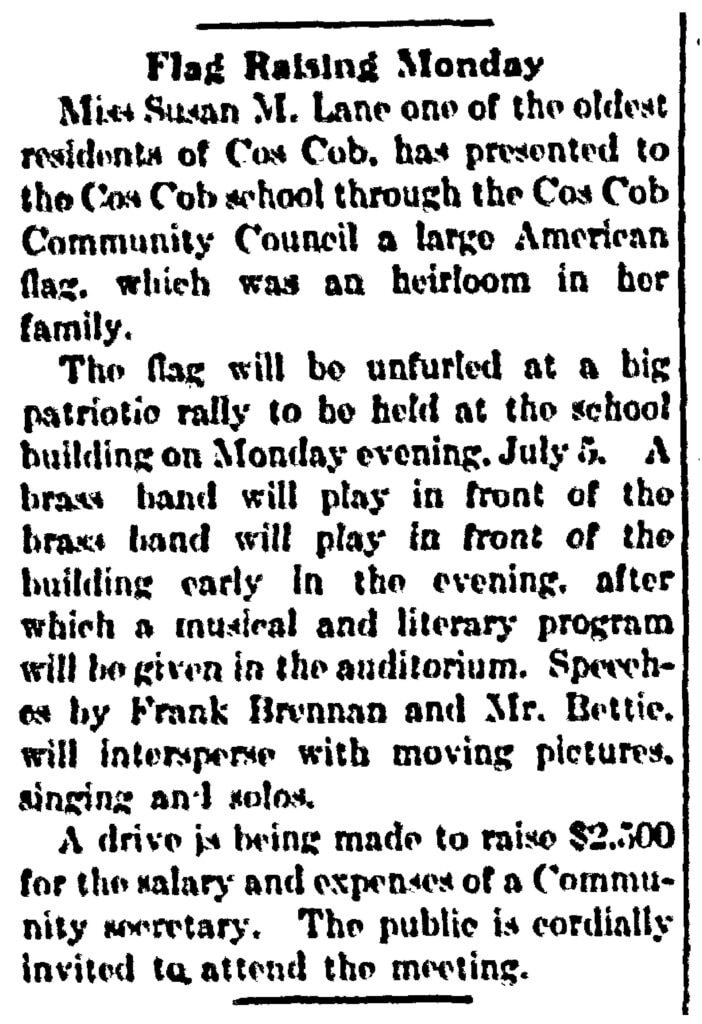

Whichever Lane woman stitched the flag, it was then presented to Cos Cob School by Susan Lane during an Independence Day celebration in 1920, according an article found in the historic newspaper database. Some more archival digging revealed that Annie Duff, a daughter of John Duff, worked at Cos Cob School at the time, and it was probably through her that the flag passed into the family.

This story may at first read as a detective story: what can be learned from documents, from oral histories, from the material object itself? And the Duff-Lane flag – and all archival work really – was very much so a mystery to be unraveled. But its history is also a love story. Within its stars and stripes, it contains the stories of sisters who banded together to thrive in a time when it could be difficult to live as an unmarried woman; of a man who loved his town and his work, so much so that he was active in both well into his 80s; and of two cousins who love their family and that family’s history, enough to preserve and share it.

The Duff descendants said it best when they made their donation: “This flag belongs here.” Nearly one hundred years later, we are so honored to welcome the flag back to Cos Cob, and so happy that we could reconstruct its history.

Many of the images in this post have been recently digitized thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). The Greenwich Historical Society’s Archival team is currently working on digitizing over 20,000 images across multiple collections, ensuring their preservation and accessibility for current and future Greenwich residents. This work is made possible by the IMLS grant.