160 years ago today, Abraham Lincoln gave one of the most famous speeches in American history – the Gettysburg Address. This short speech – only 271 words – has remained in the general consciousness of the American people ever since. Although the speech was written to dedicate a cemetery, it spoke mainly of the larger issues at hand – the war dividing the nation and the need to protect the government made of, by, and for the people. According to Lincoln, saving the Union was the only way to honor the lives of those lost, both at Gettysburg and across the ongoing war.

Lincoln did not mention slavery, the issue at the heart of the Civil War, by name in the Gettysburg Address, but he does allude to it. It was only 10 months before that Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, stating ‘that all persons held as slaves… …shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” His actions after continued to push towards the end of slavery. So when in the Gettysburg Address Lincoln says that “all men are created equal”, “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom” and that his was the “government of the people, by the people, for the people”, those in attendance understood what he meant. This war was to preserve the Union, but it was also a war to guarantee the freedom of millions.

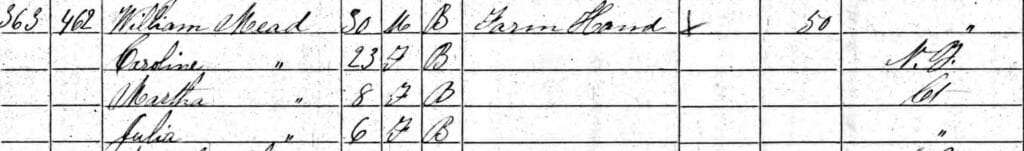

It is this notion that brings us to Greenwich, to a young man named William Mead. In November of 1863, William was in his early 30s. He worked as a farmhand and had recently procured a house of his own, a home for his family – wife Caroline, and two daughters, Martha and Julia. William was living what appears to be a happy and comfortable life. It was a life that his mother and grandmother had dreamed for him – a life of freedom.

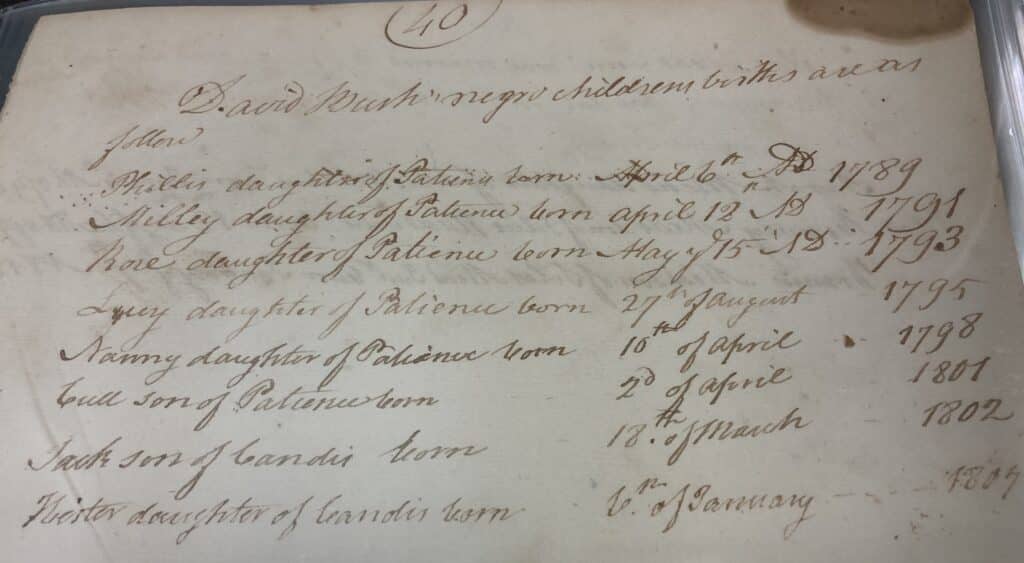

William’s mother was Hester Mead. His grandmother was Candice Bush. Both women were born into slavery. Our first record of his grandmother, Candice, marks her as an enslaved child in the household of David Bush, now the site of the Greenwich Historical Society’s Bush-Holley House. Candice was born in 1780, four years before the first of the Gradual Emancipation Acts, the series of Connecticut laws that ended slavery piece by piece until finally abolishing it in 1848. This first act passed in 1784 guaranteed freedom to all children born into slavery after its passing when they turned 25 years old. Born before its passing, this act did not apply to Candice, she had no guarantee of freedom, but 20 years later, when her children were born, their future looked bright. William’s mother, Hester, was born in 1807. She was born enslaved. She, like her mother, was forced to work for the Bush family her entire childhood. However, unlike her mother, Hester was guaranteed her freedom by law the day she turned 21.

In the end, Candice Bush was freed. The year was 1825; she was 45 years old. Three years later, her daughter Hester turned 21 and joined her mother in freedom. Hester worked as a spinner. She had two sons – William and Charles. Together, the family scraped and saved, and by 1850, Candice, Hester, and William lived together in a home of their own. Against the odds, they found freedom and had a chance to live peacefully together as a family.

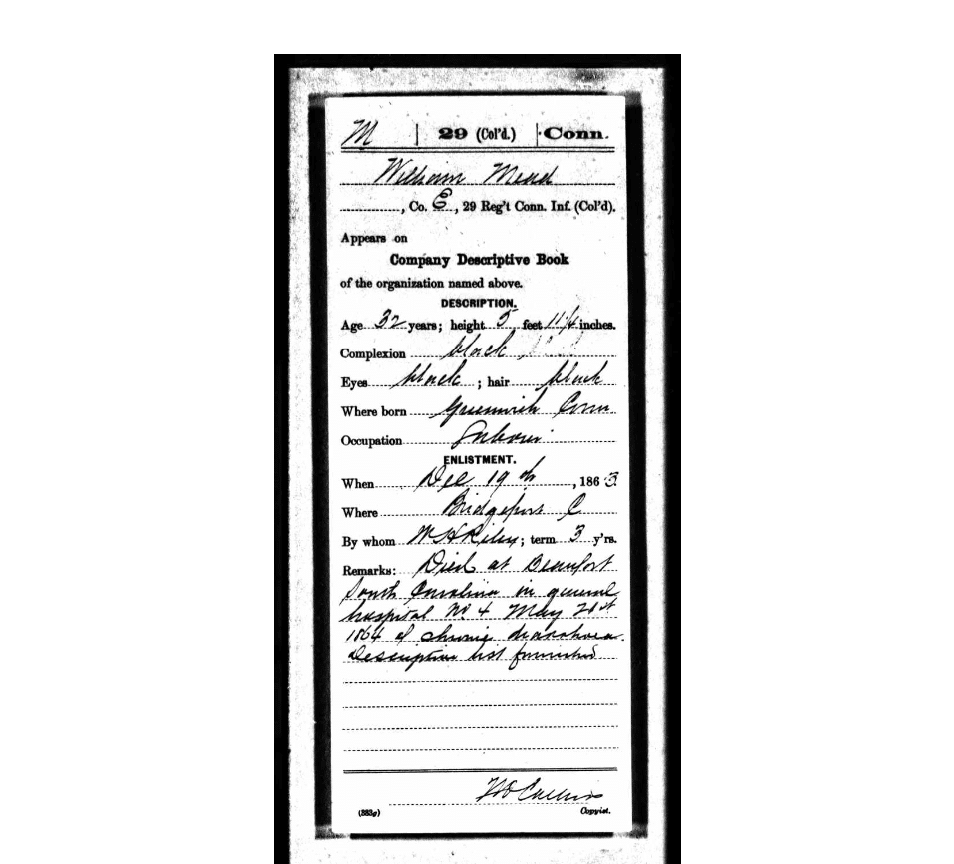

So what does the Civil War mean to a man like William Bush? This freeborn family man? The son and grandson of enslaved women? What does the Emancipation Proclamation mean? The Gettysburg Address? We cannot know for sure, but we can determine that it meant something because on December 19th, 1863, exactly one month after the Gettysburg Address was spoken, printed, and distributed across the country, William Bush followed its call – he enlisted in the Union Army.

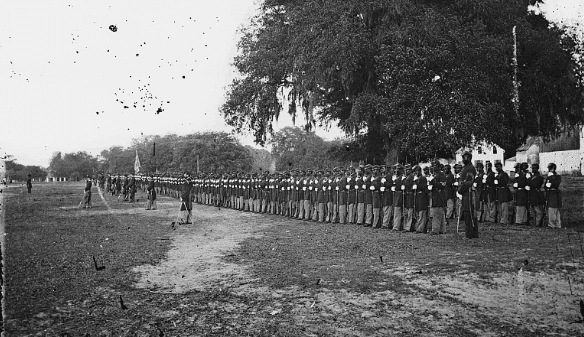

William served in the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry Regiment, the first Black regiment in Connecticut. He enlisted in Bridgeport and completed his training in New Haven. When the 29th left for South Carolina in May of 1864 to continue the “unfinished work” of the Gettysburg dead, William was on that boat. He was ready to fight.

William Mead never came back to Connecticut. He died on May 21st, 1864 in Beaufort, South Carolina. He was buried just outside of town in the National Cemetery alongside fellow soldiers.

So what did the Civil War mean to Wiliam Mead, a freeborn Black man from Greenwich, CT? He did not need to join the war. He was not forced to. Instead, William Mead, who lived the life of peace his mother and grandmother had dreamed of, set it all aside for a notion. Although born free, William lived his entire life hearing stories of the horrors of slavery. He knew on a personal level what the institution meant and the cost it carried. Because of that, he went to war in the hope that he could help make the world a better place. In the hope that he could help bring about “a new birth of freedom” to the millions who still lived in bondage in the South. It was a cause he was willing to die for.

William Mead was not alone in these feelings. According to the Connecticut census, there were around 2,200 Black men between the ages of 15 and 50 living in the state in 1860. Over 1,700 enlisted. That’s almost 80% of the eligible Black male population. The numbers are mind-boggling, but not surprising. Most of those who enlisted were only a generation removed from slavery. Like William, they had grown up with stories of slavery from their mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles, and grandparents. Some of the older ones had been enslaved themselves. These men did not join the Civil War to preserve the Union. They joined the War to end slavery. They knew on a personal level what the institution meant and the cost it carried. They dreamed of a country where “all men are created equal” and “new freedom” would be born. It is for that that they went to war.

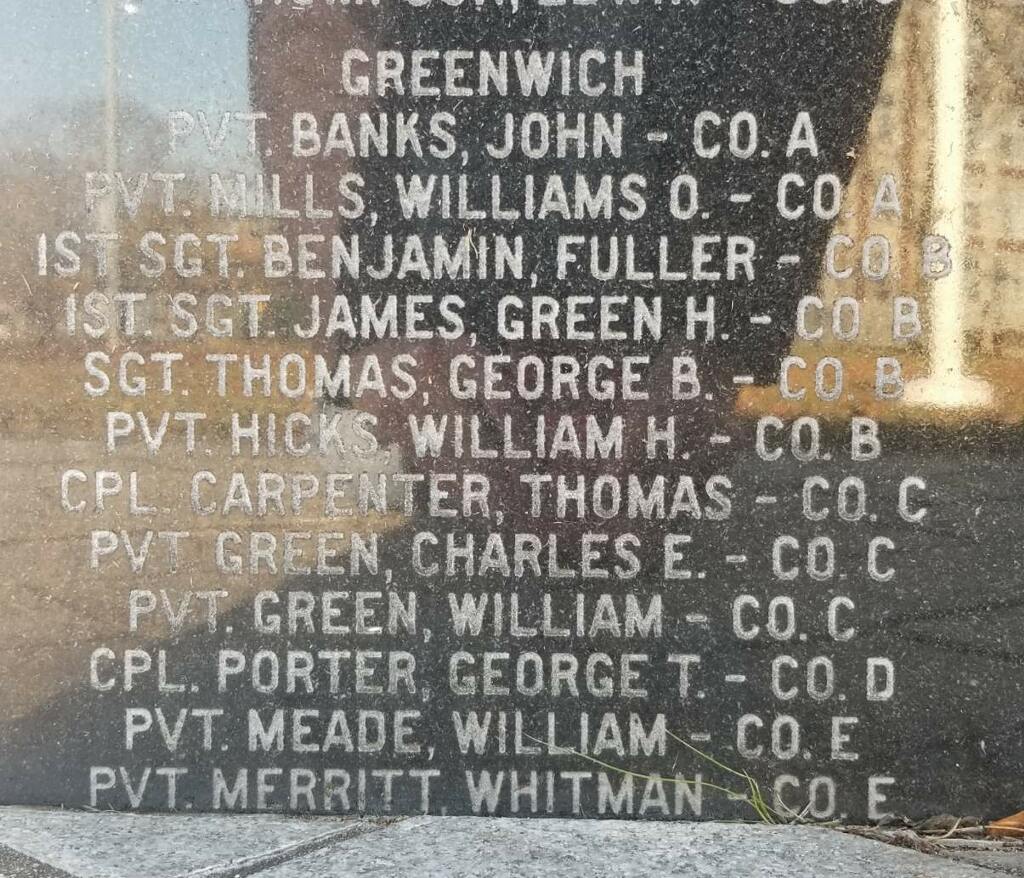

The Civil War ended in May of 1865. The 13th Amendment, which officially ended slavery in the United States was passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865. Around 5,000 men from Connecticut died in the Civil War, including 198 men from the 29th Connecticut Colored Infantry Regiment. A monument for those who served in Greenwich was placed along East Putnam Avenue in 1890. A monument for 29th was placed in Criscuolo Park in New Haven in 2008. William’s name can be found upon it along with 11 other men who served from Greenwich.

To learn more about William’s grandmother, Candice Bush, and mother, Hester Mead, please check out our page on the ongoing Witness Stones Project https://greenwichhistory.org/witness-stones/ or visit the Bush-Holley House for a tour https://greenwichhistory.org/book-a-tour/. To learn more about Connecticut in the Civil War, visit https://connecticuthistory.org/connecticut-and-the-civil-war/

If you have any information on William’s family, Caroline, Martha and Julia Mead, please contact hlodge@greenwichhistory.org.