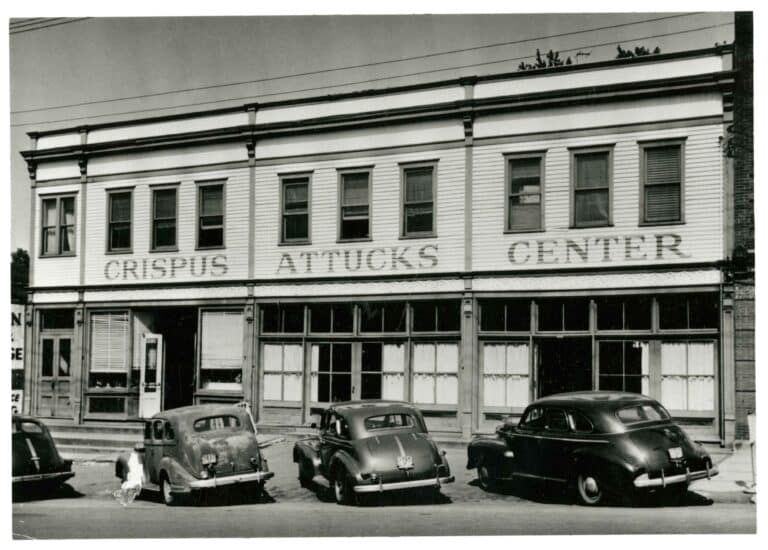

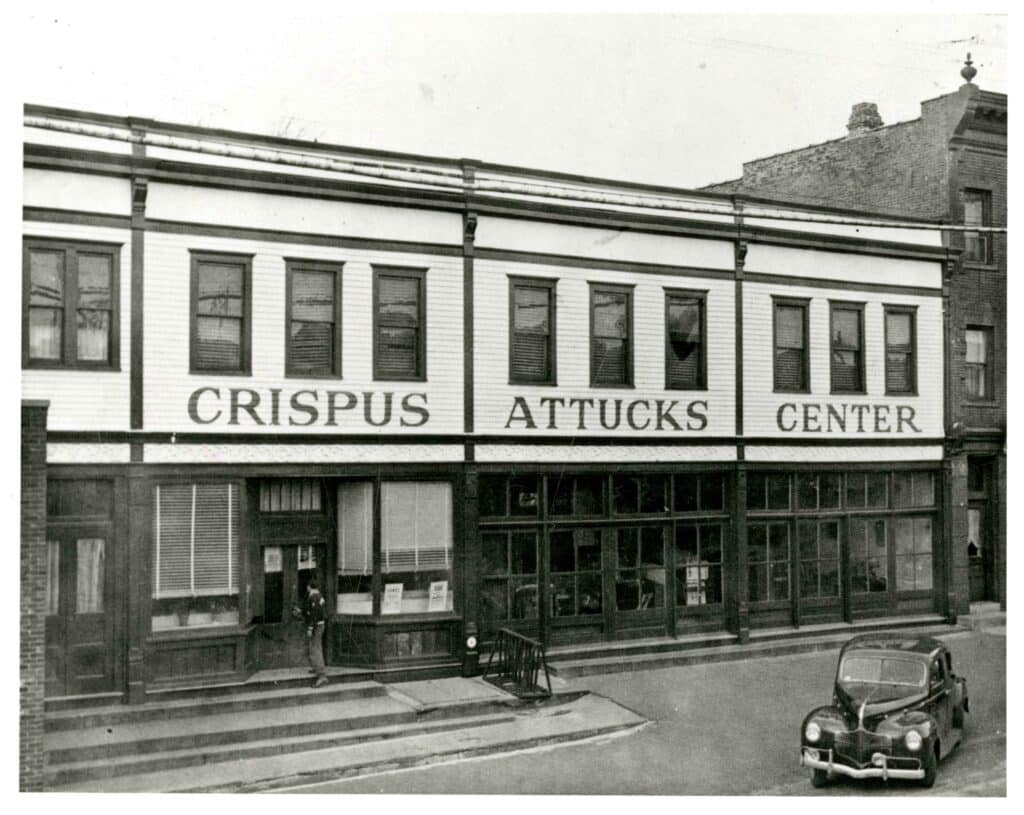

The Crispus Attucks Association was a community organization formally started in 1941 with the mission to provide programming for the Black population of Greenwich. The home of the Association, the Crispus Attucks Center, moved from the Bethel AME Church basement to 33 Railroad Avenue and then to 6 Lewis Street, and served as the heart and home of the Black community in Greenwich. The Center hosted events for all ages, functioning as a social hub, an educational resource, the organizer of an army of volunteers, and the welcome wagon for new residents. While the board of the Association, the programming, and the membership were all integrated, the Crispus Attucks Association offered sanctuary to Black citizens from the pervasive prejudice of the time – a place that was energized with opportunities and life, that would never turn them away.

The namesake of the Association, Crispus Attucks, was the first person to die in the American Revolution, the first man shot by British soldiers during the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. Attucks was of Black and Native (possibly Wampanoag) ancestry, and it is believed that he escaped enslavement in Framingham, Massachusetts in 1750. After his escape, Attucks became a sailor on whaling vessels, and was staying over in Boston between voyages at the time of the Massacre. Attucks died alongside four other men, and their deaths at the hands of British soldiers became a rallying cry during the Revolution, inspiring future Americans to fight back against oppression. After the new nation was founded in 1787, the Boston Massacre and its heroes were largely forgotten until the start of the Abolition movement early in the 19th century. Crispus Attucks was seen as the original Black patriot, the first in a line of many thousands of Black men and women who had fought for the United States, who began to demand the rights and freedoms they had fought so hard to protect. After the Emancipation and in the long shadows of the Reconstruction, Black Civil Rights activists took up Crispus Attucks’ legacy once again, reminding the country of its foundational promise of equality. It was these same values of equal rights and liberty, as well as the pride taken in Black history and Black futures, that led to the founding of the Crispus Attucks Association and community center in Greenwich.

He is one of the most important figures in African-American history, not for what he did for his own race but for what he did for all oppressed people everywhere. He is a reminder that the African-American heritage is not only African but American and it is a heritage that begins with the beginning of America.

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on Crispus Attucks in his book Why We Can’t Wait

For more information about the historical figure Crispus Attucks, visit the National Park Service’s website here, or PBS’s resource bank here.

The Crispus Attucks Center opened at 33 Railroad Avenue on November 29, 1942 to an attendance of more than 300 people. This opening gave a formal home and name to organizational efforts that the Black community had almost certainly been conducting long before 1942. By the end of 1943, the Crispus Attucks Association had furnished the new building, set up a tableau vivant for Christmas and hosted a Thanksgiving dinner, executed its first membership drive and lecture series, and sponsored its first volunteer awards. Within that first year, the Crispus Attucks Center had become a central part of the Greenwich community, a place devoted to good works, social progress, and the celebration of Black joy.

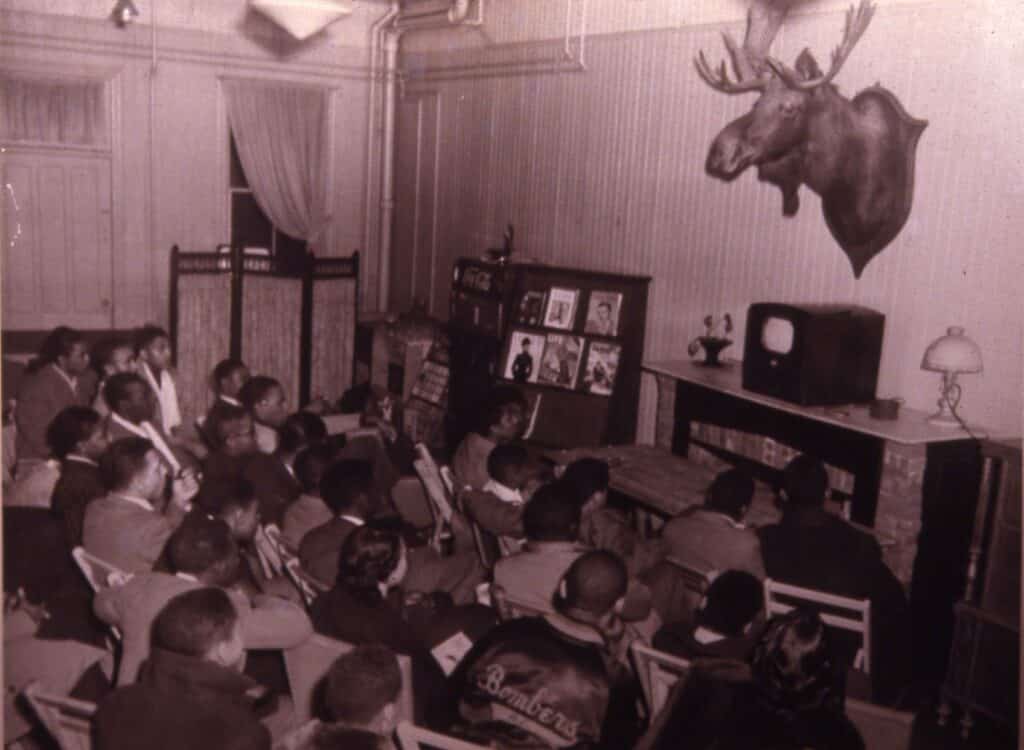

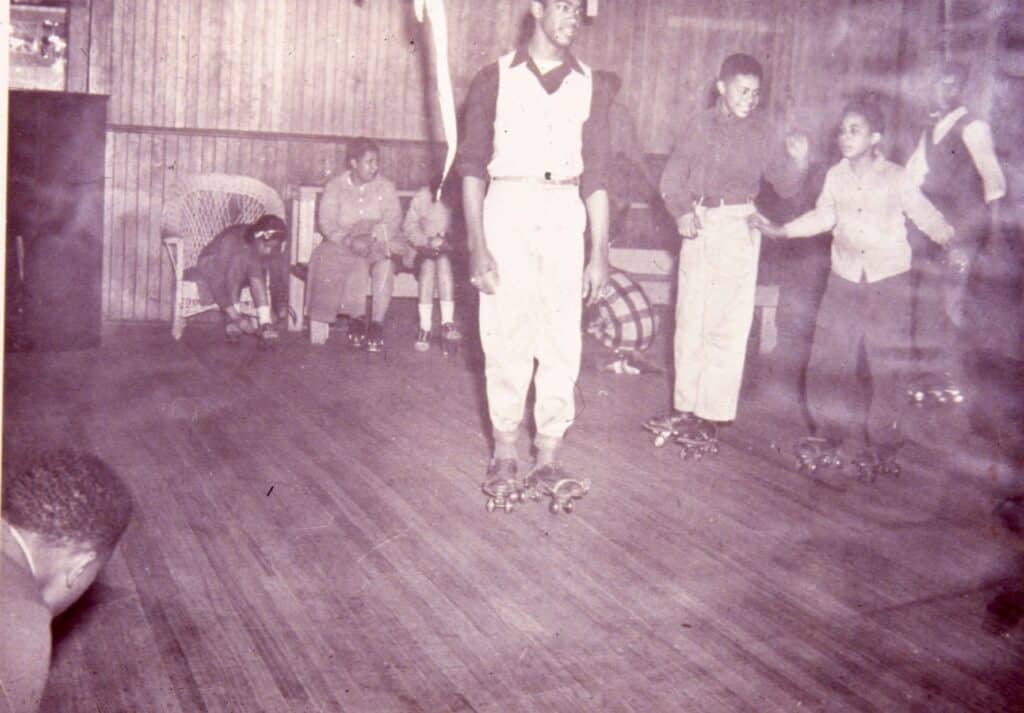

Much of the Crispus Attucks Association’s programming, particularly the events planned for young people, were social. Banquets, teas, daily lunches and dinners, card parties and pool tables were all offered to everyone in town and were hugely successful. The Center provided the Black community with communal resources, like the Crispus Attucks Center’s radio, which members could gather around to listen to programs. Dinners delivered both good food and a sense of home, which could be hard to find for domestic workers or newly arrived residents in a town where restaurants frequently turned away Black guests. Events like roller skating nights gave Black youth the chance to have fun while trying something new, an opportunity they might not have otherwise had due to segregated facilities.

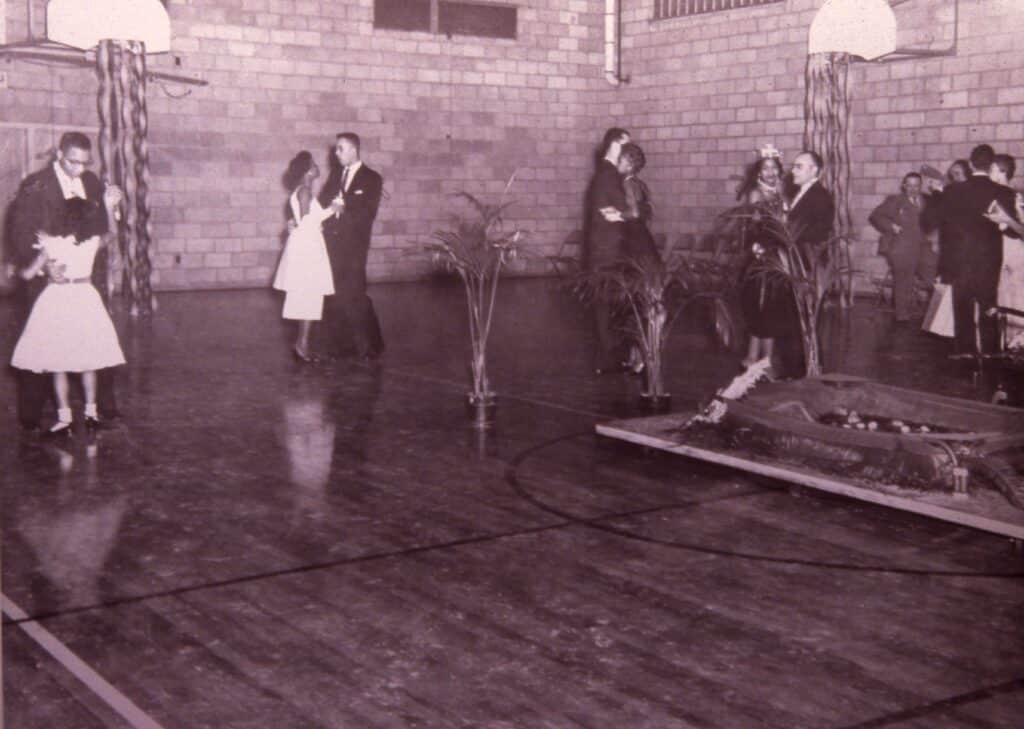

Dances quickly became another enormously popular tradition at the Crispus Attucks Association. The regular dances frequently brought in over 75 people, and were a haven for young people who didn’t necessarily have many other places to congregate safely. As a more special event, a prom was also held in later years, which possibly evolved from what was called the “Mother’s Circle Dinner Ceremony.” According to the November 16, 1949 edition of The Greenwich Time, the first Mothers’ Circle Dinner was held on the 17th of that month, and over the course of the night everyone cast votes for a “popularity queen,” similar to the election a prom queen. The photographs below are from the Historical Society’s collection, and show later prom queens, complete with a crown, throne, and crowning ceremony. Programs like dances and parties, in addition to being fun nights for local youth, also celebrated Black beauty in a time when beauty standards and products entirely favored whiteness – an issue the beauty industry continues to grapple with.

Here they hold a monthly dance for the older generation, average attendance 75, slow dances and particularly waltzes, and another for the youngsters, average attendance 100, with some pretty expert jitterbugging. You should see it some time.

— Thomas Caldecot Chubb, Greenwich Time August 22, 1946 page 5

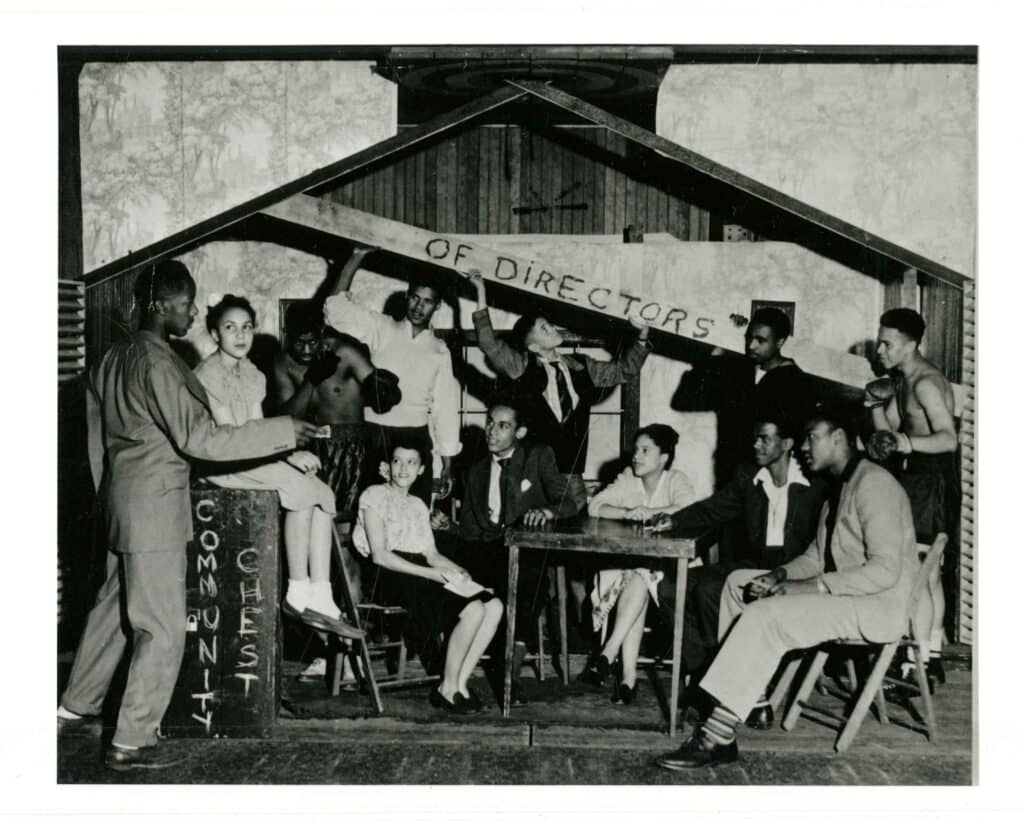

The Crispus Attucks Center also hosted plays, art classes, sewing classes, art exhibitions, and musicales. Many cultural institutions of the time – including theaters, museums, and schools – were often at least implicitly segregated, limiting the Black community’s access to art and education. By holding performances and classes, the Association created a space for self-expression and the recognition of Black talent. Among the many choir groups, the Crispus Attucks Men’s Glee Club was particularly admired, and they gave a Christmas concert in Grand Central Station on December 20, 1946. The education initiatives also didn’t stop at art classes or choir practices: the Crispus Attucks Association raised money every year to award scholarships to local Black students going on to college. These social and cultural events were in and of themselves radical statements in a time of widespread discrimination. They were a declaration that the Black community of Greenwich was thriving in spite of the racism community members often faced.

Though it was opened more than a decade before what is commonly thought of as the start of the Civil Rights Movement, the Crispus Attucks Association fought for and built a better world, one that valued Black culture and inspired future leaders. The Center held frequent lectures from prominent Black activists, including an address given by Thurgood Marshall on May 5, 1949. At the time, Marshall was still 18 years away from joining the Supreme Court as a Justice, and still an active attorney. Almost exactly a year before Marshall spoke at the Crispus Attucks Center, he had argued the Shelley v. Kraemer case before the Supreme Court, a landmark trial which ruled that states could not enforce racially restrictive land covenants, which were used to formally segregate neighborhoods. Other speakers at the Center included Jackie Robinson (the first Black player in Major League Baseball), Ruth Whitehead Whaley (the first Black woman to graduate from Fordham University School of Law and the third Black woman to practice law in New York State), and Dr. James H. Robinson (humanitarian and founder of Operation Crossroads Africa, a forerunner of the Peace Corps). Lecture series were frequently co-sponsored by the Greenwich chapter of the NAACP, which also held its regular meetings at the Crispus Attucks Center.

For more information about the Shelley v. Kraemer case, visit the National Park Service’s page here. To learn more about Ruth Whitehead Whaley’s work, visit Fordham University’s website here.

The NAACP organized lectures and forums that focused on direct political action and civil rights. In 1950 the NAACP hosted Gloster B. Current, the Director of Branches for the NAACP at the national level, who gave a talk titled “How to Use Your Ballot Wisely” that helped guide Black voters at the poles, and would likely have been especially important before the Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, which protected the right to vote from racial discrimination. The NAACP also sponsored a forum for Brotherhood Week in 1950, which featured a panel of white town residents on the topic of racial discrimination in Greenwich. Local Black students asked hard-hitting questions about why local business owners didn’t employ more Black people, why there were no Black teachers at the high school, and how a nation that claimed to have Christian ideals could practice racial discrimination. The NAACP, and by extension the Crispus Attucks Center, cultivated an environment that emphasized dignity and inspired young Black people to get involved with the political system.

For more information about the Voting Rights Act of 1965, visit the National Archive’s website here.

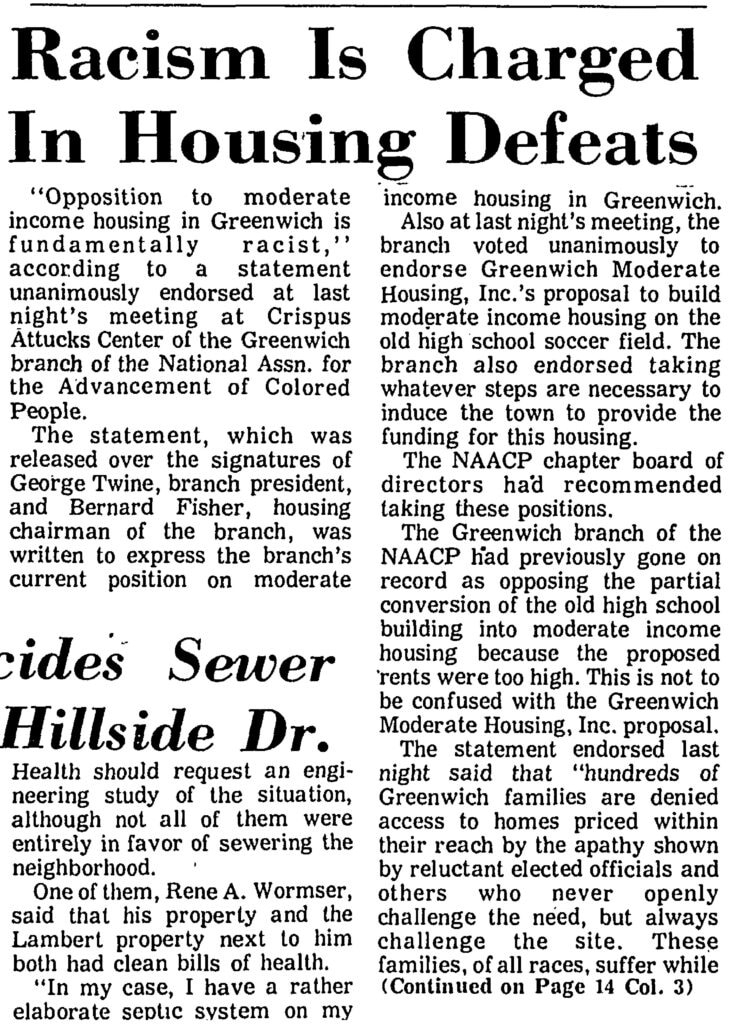

Another political front that the Crispus Attucks Association was particularly active in was affordable housing. In 1945, only three years after opening its doors, the Association petitioned the Town on the critical condition of housing in Greenwich, particularly the housing situations available to Black residents. These situations were typically in far worse shape than those of their white neighbors, and the number of real estate opportunities was shrinking due to rising prices and segregation. This petition would be renewed again and again over the years, occasionally as a result of tragedy. In 1948, the Association sent in a petition for a public housing project in the wake of a fire that killed a Mrs. Samuel R. Wiggins and her three daughters, ostensibly due to the age and lack of upkeep of the building. The issue of affordable housing, which continues to plague Greenwich to this day, disproportionately affects people of color due to the very history of racial prejudice that the Crispus Attucks Center actively fought for decades.

The Crispus Attucks Association accomplished so much more than what can be detailed here. Association members volunteered and ran donation drives to benefit Black communities in the South, the Center hosted membership drives and fundraising events, the Association started basketball and baseball teams, as well as a Boy Scout Troop for kids underserved by the town, and the Center was at the forefront of racial integration work in Greenwich. In addition to the NAACP, the Youth Council, the Women’s Civic Group, and the Golden Hour Club all called the Crispus Attucks Center home. It was a place that stretched and pushed to meet the needs of a thriving Black community. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s quote from above rings true at the local level as well as the national: Black Greenwich history is not just Black history, but Greenwich history, and it goes all the way back. Back to the enslaved people who lived and toiled in town, to the community that freed men and women built for themselves in Hangroot, to the Crispus Attucks Association, which managed to nurture fierce fun, staunch activism, and a helping hand that reached out to everyone.

The Greenwich Historical Society is honored to be the steward of these photographs of the Crispus Attucks Association, and so many others like them. The photograph collection is in the process of being digitized with the help of a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The portal to the Historical Society’s digital collection can be found here.