As reported by Anne W. Semmes

We step into the dining room of this 18th century house full of art and find the table set for 12. The blue and white china is from England. It’s a fine family setting but the people that frequented that dining table were more than family – they were artists and authors often engaging in “rambunctious conversations.” So, relates Kelsie Dalton, Greenwich Historical Society Assistant Curator of Interpretation and Collections.

Dalton is introducing us to the “heart” of the boarding house that the Bush-Holley house once was during the Cos Cob Art Colony era that stretched from the 1890’s to 1920. She begins with Josephine and Edward Holley who arrived first as renters with their three children in 1882 before buying the house in 1884. And by the 1890’s it became an artists’ retreat for the likes of Childe Hassam, with pioneering American Impressionist painter John Henry Twachtman offering classes. But all the while it is that family home, with paying guests the Holleys consider to be “part of the family,” taking their place at the family dinner table.

“So, Josephine Holley,” begins Dalton, “even though her husband Edward was technically the proprietor of the Holley House, she was really the one who’s in charge of running day to day operations. This was taking care of bills, ensuring that guests had what they needed, taking care of the servants and making sure that they knew what they had to do. If there were no servants to be hired, then she was doing that work herself. And remember on top of this, she’s also a mother to three children.”

But Josephine also finds time to be supportive of the artists. A rich trove of correspondence between Josephine and Twachtman shows “a very close relationship,” shares Dalton. “He’s frequently writing her letters…clearly leaning on her for emotional support…He’s in New York City…attempting to network and sell his art. It’s all very hard and he’s frequently writing about wishing he was back in Cos Cob.”

Dalton calls Josephine Holley “a remarkable woman, a fantastic business owner, the one who really kept this place afloat.” Besides being an active member of the Second Congregational Church Josephine was involved with the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement. “She’s a very early suffragette. She shows up on the voter registrations…Now this predates a woman’s right to vote in larger more national elections. But this is the point where Greenwich allows women to vote in town meetings solely on matters of education.”

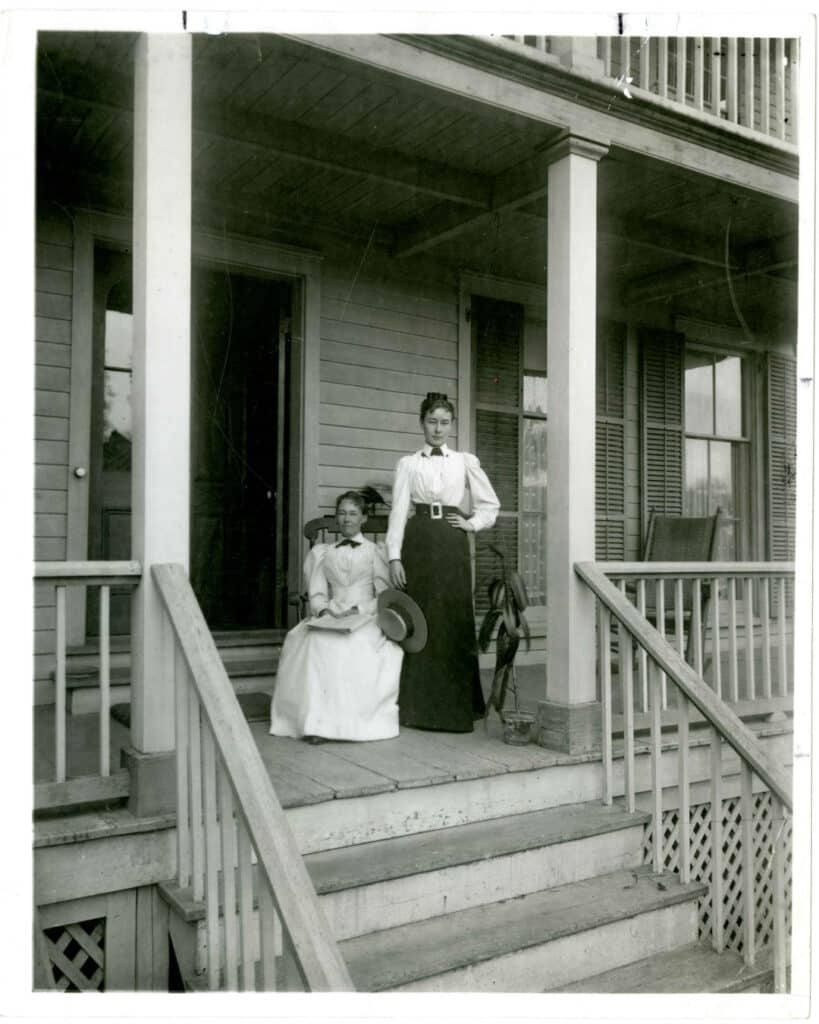

Also showing up on that voter registrations is Josephine’s daughter Emma Constant Holley. In Josephine’s later years, Dalton shares, she cedes the running of the Holley House to her daughter, Emma Constant.

“She really became the heart and soul as her mother was before her of the boarding house,” says Dalton. “In 1900, she married Elmer Livingston MacRae, an artist who is also a student of Twachtman which is what first brought him to the Cos Cob Art Colony…So, his children and his wife were some of his most favorite models to paint.”

But Emma Constant Holley MacRae had her own passion, flowers. “She is a flower arranging artist,” says Dalton. “She has commissions all over Greenwich. She does all of the decorations for parties at the Holley House. And in 1915, she wins her first prize at a flower show at the Westchester Fairfield Horticultural Society show. And then, in 1921, at the first international garden show in New York…she takes first prize…She travels all over the country giving lectures at various garden clubs about flower arranging throughout her life.”

Widowed in 1953 with Elmer MacRae’s death, Emma Constant is holding forth in the Holley House four years later when she learns of the plans for I95 with its trajectory to go right through the Holley House. She offers to sell the House to the Greenwich Historical Society, which thus accomplished, leads to its being established as a National Historic Landmark. “This pushed I 95,” says Dalton, “to creating a bend in the highway and saving the House.

“So, not only does she save the structure that we’re standing in, but she also saves the context of the Cos Cob Art Colony for future generations.”

As for that third generation. The MacRaes had twin girls, Constant and Clarissa. Dalton displays a portrait of each as young girls. Hassam has painted Clarissa, and MacRae, Constant.

“And they grow up in this House surrounded by artists and authors,” tells Dalton. “The Bush-Holley house really is their playground…and they are very popular models both for their father and for other artists in the art colony.” Dalton imagines what their life would be like, “climbing trees and hanging out with your cat, but then you go to dinner and there’s Childe Hassam talking about impressionist art or the etchings that he’s been working on.”

And as they grow older, tells Dalton, “They also join the junior suffrage league and then grow up in 1920 and receive the right to vote. So, this is really the culmination of three generations of women who were pushing for the suffrage cause. So, they grow up here, they get married, they move out…of a 250 -year-old house that has seen so much history.”

The last word is offered by fellow tour participant Davidde Strackbein, long-serving trustee of the Historical Society. “Aided by modern technology, the tour shone a light on the original source materials they chose to preserve and how beneficial they are now, almost a century and a half later, when telling the stories of the Holley women’s roles in adapting to the changing economic, social and cultural demands of their times.”