By Robert Marchant | Greenwich Time | February 12, 2022

GREENWICH — Few markers of slavery exist in southern Connecticut, reminders of a time when men and women were bought and sold like property or livestock.

Two of them stand at Union Cemetery in Greenwich — the headstones of Hester Mead and her mother Candice Bush, both born into slavery at the Bush homestead in Cos Cob, now the site of the Greenwich Historical Society.

“They’re the only enslaved people in Greenwich, or formerly enslaved people, to have headstones,” notes Heather Lodge, a researcher and educator at the Greenwich Historical Society.

But more stone markers are coming, as a way to commemorate the lives of farm laborers, servants, cooks, craftsmen and nannies who lived in bondage in Greenwich for over 200 years.

As Black History Month proceeds, middle-school students, teachers, librarians and archivists in Greenwich have been working with the Historical Society and an educational organization to create stone markers — called “witness stones” —for enslaved men and women. The students and researchers are slowly documenting the history of the enslaved community, stitching together a narrative of resilience and despair from faded wills, census records and land documents.

“These people led really incredible lives,” said Lodge, manager of youth and family programs at Greenwich Historical Society, describing the bonds between them as what must have been a powerful and sustaining force in a hostile world.

The work is proceeding with input from the Witness Stones Project, an organization founded by a Guilford history teacher that has been commemorating the lives of enslaved people in the Northeast with memorial markers beginning in 2017. Thus far in Greenwich, four men and women who were enslaved at the Cos Cob homestead of the Bush family — Cull Bush Sr., Patience (surname unknown), Candice Bush and Hester Mead — have been commemorated with stone markers.

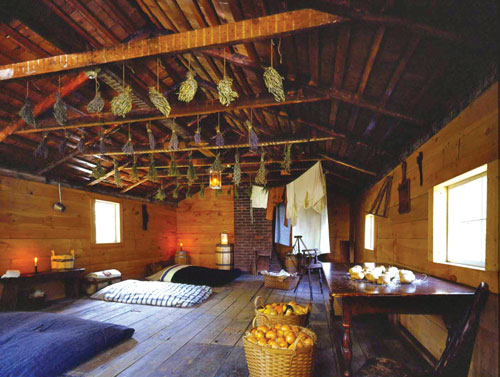

The family of David and Sarah Bush were the largest slave-owners in Greenwich, with some 15 enslaved men and women once working and living at the site near Cos Cob Harbor.

The Bush family, whose ancestors came from Holland, are unrelated to the family of Presidents George and George H.W. Bush of Greenwich.

Now the researchers are looking to trace the lives of Cull Bush Jr., the son of Cull Sr., and Jack, the son of Hester Mead.

Cull Bush and his domestic partner Patience — official marriages between enslaved men and women were not often permitted by owners — had six children, five girls — Phillis, Milley, Rose, Lucy and Nanny — and a boy, Cull Jr.

“As the girls would come of age, they were slowly given away to work other households, so the parents were separated from their children. Except for Cull Jr., the only boy, he got to stay here in the house,” said Lodge. Family separation was a fact of life for men and women who were kept in bondage, she said.

It appears that the children of Cull and Patience Bush were sent out to other homes in Greenwich, Lodge said, perhaps through a kind of rental arrangement, as indentured servants.

Cull Sr. was eventually freed, not long after the death of David Bush in 1797. “He (Cull Bush) is left with this dilemma, he’s free, but his significant other and his children are not,” said Lodge.

A man of evident drive and determination, Cull Sr., who may have had training as a miller, went to Hangroot, the freed Black community of Greenwich around Round Hill Road, the records show.

“Very quickly he gathers enough money to buy property in Cos Cob, and moves back, so he can be near his wife and children. He stays in Cos Cob for the rest of his life,” said Lodge. “He continues to trade in land for the rest of his life. We found documents showing him buying and selling land to different white people all over Greenwich …. He was exceptional. He is someone who was as a youth enslaved, but he was able to amass money and reputation. Then he was able to give land to his son.”

The lives of Candice Bush and her daughter, Hester Mead, were also brought to light by the researchers, who included students at Greenwich Academy and Sacred Heart Greenwich. Candice and Hester eventually obtained a house together after they were freed, becoming land owners. Hester left behind a will at her death in which she gave away clothing, silverware and books, “which shows she could read and write,” Lodge said. Hester was also a painter — a painting donated to the Historical Society by the Mead family has been attributed to her.

“Another testament to how she was able to make a life for herself, an identity for herself in freedom,” Lodge said.

Hester’s son, William Mead, enlisted in the 29th Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers (Colored), one of the Black units raised by the Union during the Civil War to alleviate a shortage of manpower as the fight dragged on. Mead died of illness near Beaufort, S.C., in 1864.

“This son of an enslaved woman, and grandson of an enslaved woman, fights to end slavery,” said Lodge.

While the stories of their individual lives are unique and intriguing, Lodge said, there was nothing exceptional about their status as enslaved workers and servants in Connecticut.

“It wasn’t an uncommon thing. Many farmers were enslavers; so were priests and doctors, teachers and legal officials, and even towns themselves. There was a woman named Dinah, in the town of Guilford, who was collectively owned by the town,” the Greenwich educator said.

Scholars say slavery touched every town in Connecticut; the numbers involved were thin but widely spread. A quarter of the wills probated in 1776 referenced slave “property.” Slavery was not fully abolished in Connecticut until 1848, following a gradual emancipation, long after New York state and Massachusetts had ended the practice.

The work of researching the past lives is painstaking. For research on women, it has been even more difficult because of a scarcity of documentation. In nearly all cases, women’s names weren’t printed on census record in Connecticut until 1840, they were only represented with a check mark on the documents. Lodge says the goal is to research all of roughly 300 enslaved men and women who lived in Greenwich, including native Americans.

Lodge has endured plenty of eye-strain looking at the old wills and land records —“it’s faded, it’s blotched in spots, the spelling wasn’t standardized.” Students, alas, can’t offer much help: “most kids can’t read cursive anymore, let alone 17th century cursive.”

At Sacred Heart Greenwich, seventh-graders have been exploring the concept of slavery, and they will begin working with documents and a specific life, Cull Bush Jr., in coming weeks, said Angela Carstensen, Director of Library Services at Sacred Heart Greenwich.

“That’s the really effective part when they start learning about one person’s life,” said Carstensen. “They can see where the person lived. And seeing these primary documents — they’ll see inventory of the household goods, and the enslaved people are listed next to pots and pans, listed next to animals. That’s what really gets to them.”

The students will give a presentation on the research at the Greenwich Historical Society May 25. The new biographies will be put on the historical society website, and the documents will be made available for research at the society headquarters in Cos Cob. The material on slavery is also given on every house tour at the site.

It’s painstaking work, and laborious in more ways than one, said Lodge, but rewarding for everyone involved.

“They’re telling the stories of people who have been forgotten. In a way, they’re bringing people back and remembering them,” she said. “That’s something that sticks with you.”