In museums, it can be easy to feel like we have entered another world, one disconnected from our own contemporary reality. Today’s visitors to the Greenwich Historical Society are provided tours of Bush-Holley House that frame its history in terms of the great artists who stayed and painted there during the Cos Cob art colony period. But it was also truly a home to the Holley family and those who lodged there, the site of struggles, friendships, and tragedies. Surviving letters in the Greenwich Historical Society archives offer a glimpse into the friendship that flourished between the painter John H. Twachtman and the proprietress of the boarding house, Josephine Holley. While it is impossible to get the full measure of any person or relationship from the fragments of a correspondence – like listening to a one-sided conversation completely outside of its context – these letters still offer a wealth of clues that suggest the affectionate bond between Josephine and Twachtman, and show both Twachtman’s love for Cos Cob and the difficulties he faced in his career as a painter.

To learn more about John Henry Twachtman’s time in Greenwich, visit the online exhibition Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman.

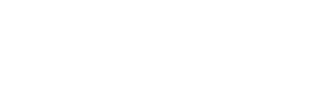

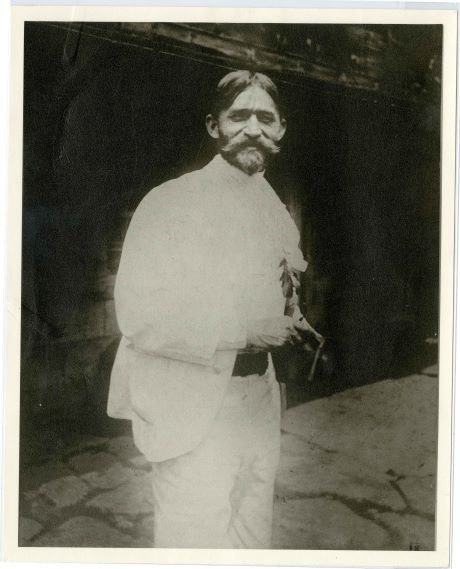

As a painter now heralded as one of the most innovative among the great American Impressionists, Twachtman’s life and art have been thoroughly researched and his artworks exhibited in galleries all across the United States. Josephine Holley, who offered support to the many talented artists who stayed at the Bush-Holley House – in addition to running a business and raising a family – has not been so thoroughly studied. Born in Bedford, New York in August of 1848 to parents Solomon and Hannah Rundle Lyon, Josephine was descended from some of the oldest families in Greenwich, and some of the earliest settlers in the first American colonies. In 1866, Josephine married Edward P. Holley at just 18 years old and took the Holley name, setting the path that would eventually lead to the Bush-Holley House as we know it today.

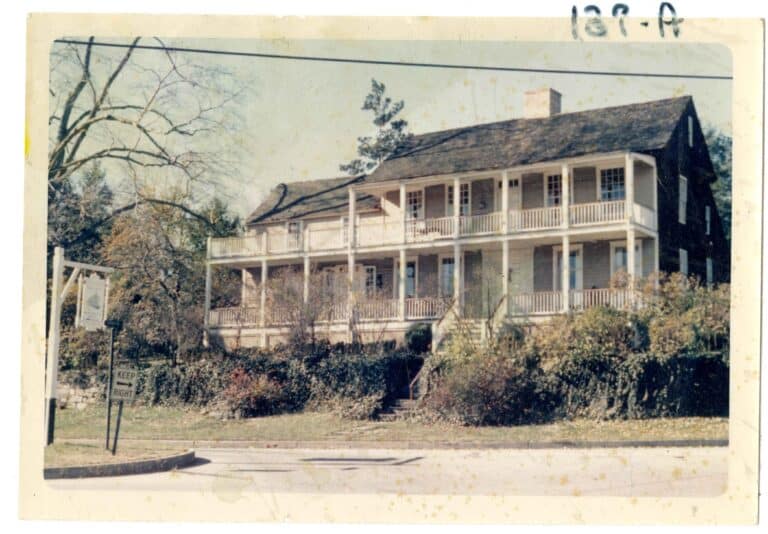

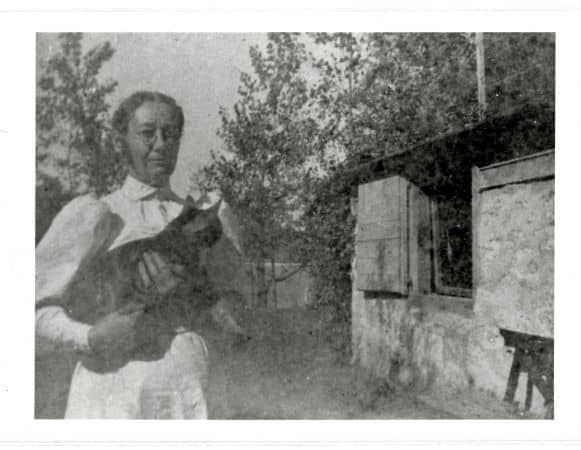

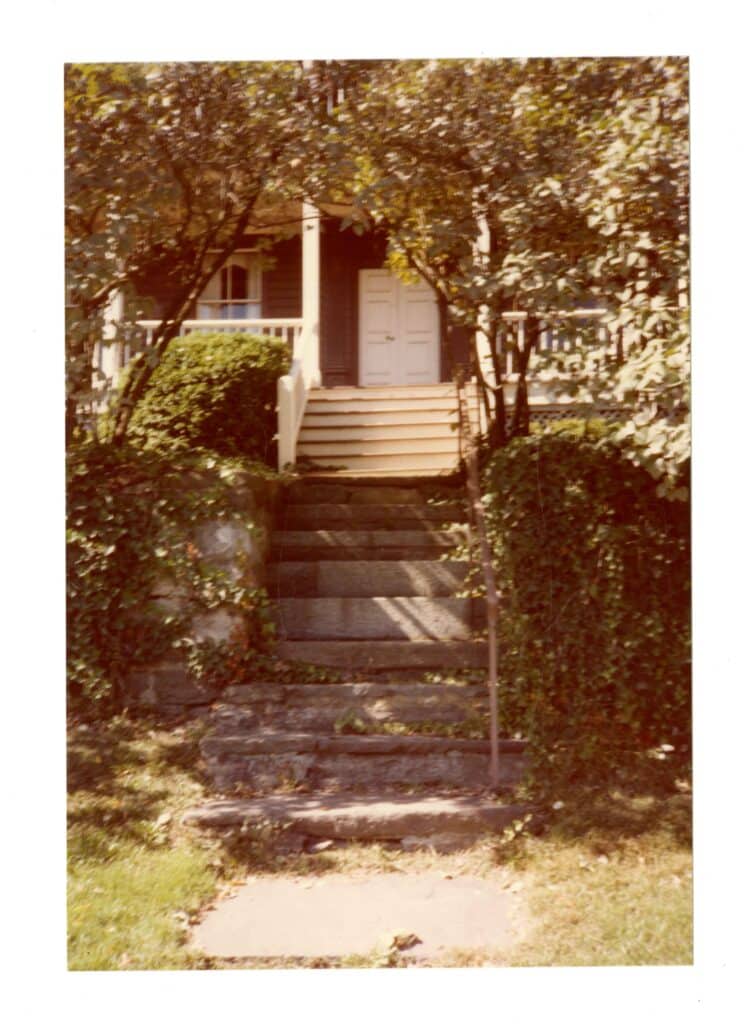

The Holleys first opened their home to boarders while living in a large house they called the Holley Farm on Stanwich Road in Greenwich, and this estate is where artists like J. Alden Weir first visited and painted the area. However, Edward P. Holley set about expanding and improving the property, an investment which did not pay enough of a return: by 1881, the Holley Farm had been foreclosed on and sold. In 1882, the Holleys moved to the then-Bush Homestead in Cos Cob to start anew. The family at that time consisted of Edward and Josephine and their three children: Edward (known as “Eddie” and born 1868), Josephine (known as “Josie” and born 1869), and Emma Constant (known as “Constant” and born 1871). The family settled in well, and became popular on the Lower Landing, as the waterfront area on Cos Cob Harbor where the house was situated was often known. They would remain popular for the next 75 years while multiple generations were raised in the house.

Unfortunately, a tragedy struck in 1887, when all three children and Mr. Holley fell ill with measles. Josie Holley died at age 17 from the illness, after a lifetime of “delicate health,” according to local newspaper reports. The Holleys must have been devastated, though there is no record of what Josephine endured as a mother during this period of sickness and tragedy. While it is unlikely that the boarding house was open to guests while measles swept through Cos Cob, Josephine still would have been the main caregiver, as well as being responsible for keeping the household running without active revenue, even as she grieved the loss of her daughter.

Although as a man and head of the household Edward Holley was considered the proprietor of the boarding house, evidence from personal letters indicate that Josephine was largely in charge of its day-to-day operations. She would have overseen the cooking and cleaning, kept stocks of pantry and everyday supplies, paid bills, saw to the needs of her guests (including wake up calls), maintained the never-ending correspondences that informed her of when new guests would be arriving and leaving, and figured out how to fit them all in.

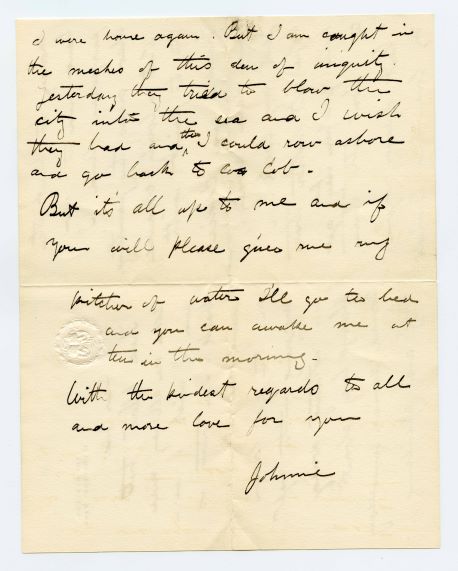

Business got busier when John H. Twachtman began hosting classes in Cos Cob with J. Alden Weir in 1891. The pair had been teaching at the Art Students League of New York City, and Twachtman purchased his own property in Greenwich on Round Hill Road in 1890. Artists, particularly those painting in the Impressionist style, were attracted to the area by the quaint views of the harbor and docks, the pervading feeling of quiet country life, and the ease of traveling by train from New York City. They came to the Holley House for the beautiful scenery and the good company. We don’t know what drew Josephine and Twachtman closer together; perhaps it was the loss of Twachtman’s nine-year-old daughter Elsie in 1895 to scarlet fever, after which Josephine might have been a source of sympathy and solace, given the loss of her own child. From their letters, it’s clear that Twachtman felt himself one of the family, and perhaps their similar senses of humor and familiarity naturally led to their friendship.

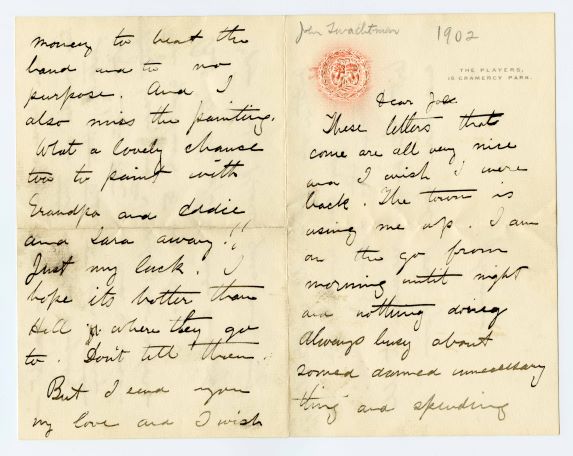

The Greenwich Historical Society Library & Archives is home to several boxes of correspondences from the Holley and MacRae families, and a number of letters in these collections are from or mention Twachtman. One such letter, reproduced in full below, was sent by Twachtman at the start of 1902 when he was working in New York City. In it, Twachtman disclosed to Josephine how tired he was of the city, writing that “The town is using me up.” He was constantly on the go, possibly meeting with galleries, art dealers, prospective students, and generally dealing with the business of art. According to Twachtman, this business side of things was expensive (possibly including wining and dining of important contacts) and it left him no time to paint. It could be easy from our present-day position to see Twachtman’s works and enjoy his talent and his achievement as forgone conclusions, but this letter shows how hard Twachtman had to work to maintain a foothold in the art world. Any modern artist who has had to take time away from their creative passion to manage their social media will probably recognize the challenge.

Implicitly, Twachtman also acknowledges another challenge in the letter: family. While he clearly indicated that he missed his friends and family, Twachtman responded to the news of their absence from home by writing, “What a lovely chance too to paint with Grandpa [Edward P. Holley] and Eddie [the Holley’s son] and Sara [Eddie’s wife] away!! Just my luck. I hope it hotter than Hell where they go to. Don’t tell them.” It must have been hard at times to get serious painting done with a cast of rotating characters moving through the house, in addition to the extended family. This theme recurred throughout Twachtman’s life, and he was frequently away from his wife and children while working on paintings or exhibitions.

This line from the letter also indicates the closeness Twachtman felt for the Holley family, so much so that he referred to Edward P. Holley as “Grandpa.” Twachtman teases that he hoped the weather was terrible where they went (likely either Florida or Cuba, Mr. Holley’s favorite winter haunts), because the group left home while Twachtman was away, and so couldn’t take advantage of their absence to paint in peace. This joke also reveals Twachtman’s impish sense of humor, and that he was comfortable joking in that way with Josephine. Perhaps her sense of humor was similarly impish, and Twachtman knew she would appreciate the joke. Twachtman’s affection for Josephine and the Holley family is clear throughout the entire letter, but it’s highlighted especially in the last line: “With the kindest regards to all and more love for you [Josephine]. Johnnie.” Whatever brought the pair together, Twachtman’s writing shows how he trusted and cared for Josephine, and how much of a home Cos Cob and the Holley House had become for the artist.

Josephine outlived Twachtman by 14 years, and died in 1916 of pneumonia. She was an active member of the Second Congregational Church, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and an early proponent of women’s suffrage. Her name appears on voter registration lists as early as 1912, when women were only allowed to vote in town meetings on matters of education. At her funeral, the pastor of the Second Congregational Church Reverend Charles Taylor said in her eulogy:

It was here, in the midst of her loved ones and in the changing and ever increasing circle of friends that came and went, that she wove that wonderful fabric of character and service which all shall treasure as a priceless possession. Here was a love that calculated not the cost of sacrifice, nor ever implied that it had a cost. The unselfishness of her daily life was so habitual and natural to her that it almost made necessary the perspective of death to fully appreciate it. The simplicity, frankness, and common-sensibleness of her spirit might disguise to the casual observer the essential divinity which abides in these homely virtues, but the initiated recognized that in these resided one of the secrets of her power.

Reverend Charles Taylor

Josephine was by all accounts a capable, caring woman – a keystone for her family and for the Cos Cob art colony. When we remember the American Impressionists and the generations of artists who were inspired by them, we should also remember Josephine Holley and her power.

It can be easy to get caught up in the tangible objects that have been preserved from these historic moments in Greenwich history: the beautiful paintings of an unobscured harbor, the ancestral house of a wealthy family, and the centuries-old luxuries that house contains. And the people who created and loved these things can seem so impossibly, unreachably alien. Indeed, it is hard to imagine Cos Cob Harbor without the shadows and noise of a surging (or, just as frequently, traffic-jammed) I-95. But the snippets that these letters provide, along with their context, remind us of the achingly familiar humanity of those historic people. They too went fishing in the harbor, celebrated anniversaries, worked hard to make ends meet. They lost loved ones to devastating disease, a heartache which has become all too real again during the Covid-19 pandemic. They struggled to balance their work with the demands of family, and they reached out to those they trusted in times of difficulty. As humans, we have always laughed and joked and longed for home.

The exhibition Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman, curated by Lisa N. Peters Ph.D. is on view at the Greenwich Historical Society through January 22, 2023. The entirety of the surviving letters John H. Twachtman wrote to Josephine Holley can be found digitized as part of the John Henry Twachtman Catalogue Raisonné, a free digital resource offering a complete record of all artworks by Twachtman, authored by Dr. Peters and presented to the public in collaboration with the Greenwich Historical Society.