By Kate Eagen Johnson | Antiques and the Arts Weekly | November 1, 2022

COS COB, CONN. – “I can see how necessary it is to live always in the country – at all seasons of the year.” American Impressionist John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902) shared this certainty with close friend and fellow artist Julian Alden Weir in 1891, a few days after adding acreage to his small farmstead in Greenwich, Conn. Twachtman’s guiding belief in the inspirational power of place and nature shines through the exhibition and catalog titled “Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman.” Visitors can take in the intriguing presentation at the Greenwich Historical Society in Cos Cob until January 22.

For the Greenwich Historical Society (GHS), mounting an exhibition on Twachtman’s Greenwich period strongly aligns with its mission to preserve and interpret aspects of local history, with special attention paid to the Cos Cob Art Colony of Impressionist painters, a group made well known through the scholarship of Dr Susan G. Larkin. In late 2018, GHS opened its reimagined and expanded campus, integrating new state-of-the-art museum, library and archival facilities with Art Colony-related buildings, including the boarding house run by the Holley family. In that structure, now called the Bush-Holley House, visiting creatives availed themselves of all manner of sustenance – art instruction and stimulating conversation as well as hearty meals. In the catalog foreword, GHS’s executive director and chief executive officer Dr Debra Mecky recognizes Twachtman and Weir as the founders of the Art Colony, which flourished between 1890 to 1920 and is considered the first in Connecticut.

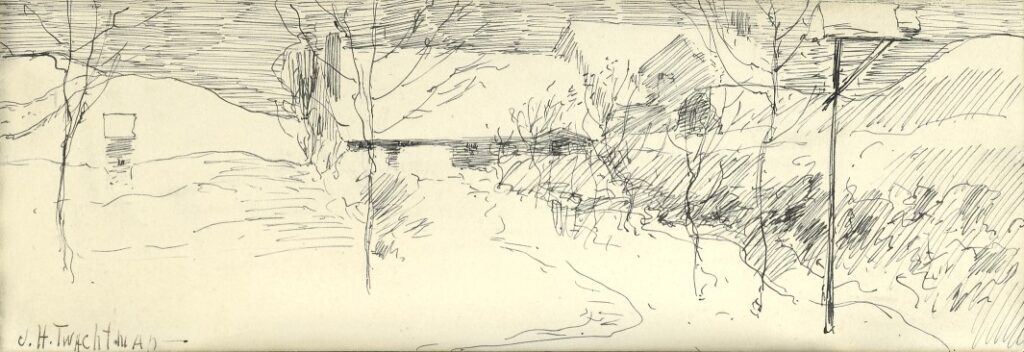

A multi-pronged effort to document and explore Twachtman’s circumstances and artistic output in Greenwich fits squarely with GHS’s “bricks and mortar” achievement. Through the exhibition and catalog, Dr Lisa N. Peters, the independent art historian and curator who served as guest curator, investigates his range of creative expression during the 1890s, the decade he spent in the coastal Connecticut town. The monographic exhibition – featuring 18 works, photographs of Twachtman and his circle, and other archival items – is accompanied by a thematic installation of the Bush-Holley House and by an appealing mix of onsite and offsite programming.

In a related vein, the John Henry Twachtman Catalogue Raisonné (www.jhtwachtman.org), also authored by Peters and supported by GHS, functions as a clearinghouse for information about the painter, pastelist and etcher and his oeuvre. This online offering, rich in visual and written content, stands on its own as a continually updated, academic resource. It is also a valuable reference for visitors who want to learn more about Twachtman’s career and art after touring the exhibition. Peters began work on the catalogue raisonné in 1987 when it was sponsored by Spanierman Gallery. She is committed to adding new information and insights until 2025.

But back to the exhibition. In “Life and Art,” Peters links Twachtman’s artistic development during the 1890s with the alterations he made to his residence and surrounding landscape, views of which were his favorite subject matter.

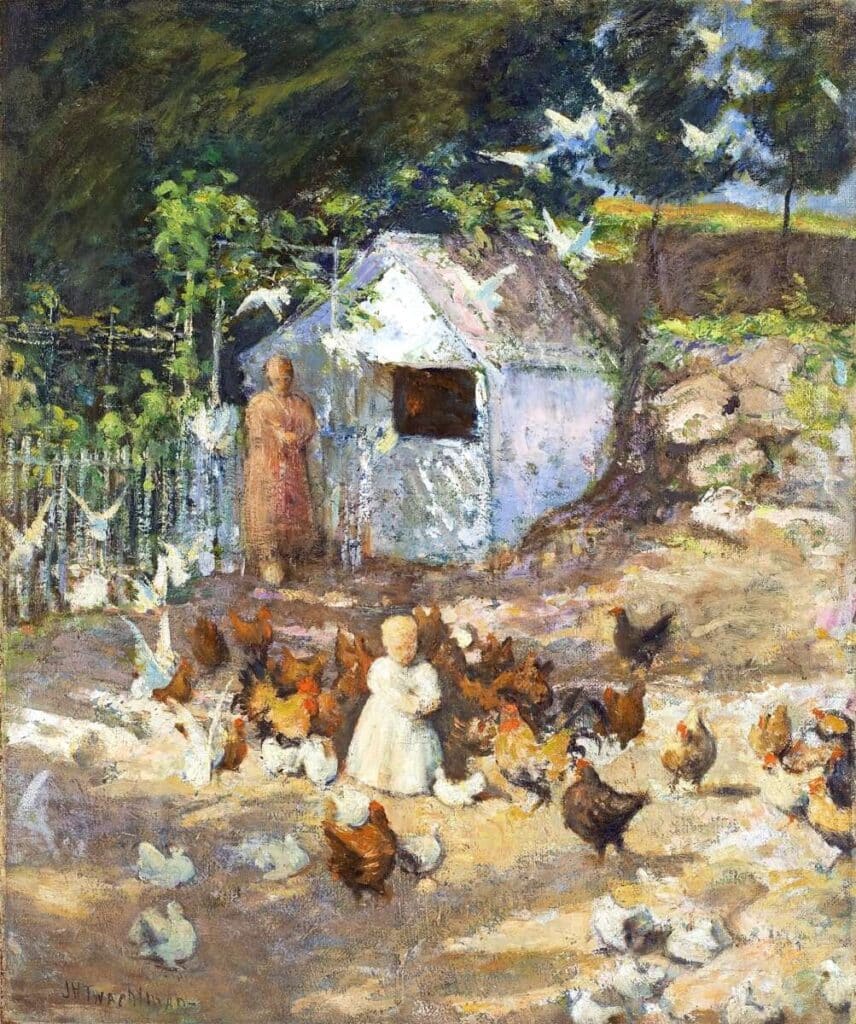

In the 1880s, Twachtman had become acquainted with the beauty of rural Connecticut when visiting Weir at his own country place in Branchville, Conn. In 1890, he acquired a farmhouse and three acres in an out-of-the-way section of Greenwich called “Hangroot.” The following year, he purchased an adjoining 13-acre parcel, varied in terrain and containing a picturesque creek. During the next decade, the artist modified and expanded the main structure while also building stone walls and establishing flower and vegetable gardens. He improved the house and grounds with his growing family in mind, all the while feeling little need to portray scenes beyond his demesne.

Maggie Dimock, GHS’s curator of exhibitions and collections and coordinator of the exhibition and catalog project, stated that “we really want to evoke this idea of situating visitors in that natural landscape around that house which was so personal and so inspiring to Twachtman as an artist. He really felt some kind of connection to that particular plot of land – the Horseneck Brook that ran through it, the waterfall that was just up the brook…he raised his family there.”

Since Twachtman exerted much energy remodeling the farmhouse, and depicting it from various angles, it was essential that Peters understand the structure’s construction history. The knowledgeable current owner of the house, John Nelson, architectural historian James Sexton and Charles Hilton Architects worked together to document and visually represent the changes Twachtman had executed. Dimock underscored how the structure “has become this important primary resource in contextualizing the paintings that Twachtman made during the decade he lived there because he almost never dated any of these paintings.” (The artist rarely dated his work after 1883.)

Twachtman is considered among the most inventive of the American Impressionists. He was a founding member of The Ten American Artists, or “The Ten,” a loosely affiliated group that broke from the Society of American Artists in order to mount its own shows. As a young man in Cincinnati, Ohio, Twachtman labored as a window shade decorator while receiving art instruction from Frank Duveneck. In 1875, he accepted Duveneck’s invitation to travel with him to Munich for further training, the first of several trips he would make to Europe. When back home in North America, Twachtman, having married in 1881, tried his hand at various pursuits in order to support his family. These ventures took him to Cincinnati and other towns in the Midwest, Ontario and New York. (He also relied on the munificence of his father-in-law for many years.)

Once settled in Greenwich, Twachtman taught at the Art Students League in Manhattan and at the Holley House in Cos Cob to help pay the bills. Twachtman charted his own course, refusing to sacrifice his artistic vision for commercial success. In fact, the Cincinnati Art Museum’s “Waterfall, Blue Brook” is the only work acquired by a public museum during Twachtman’s lifetime. It is included in the exhibition.

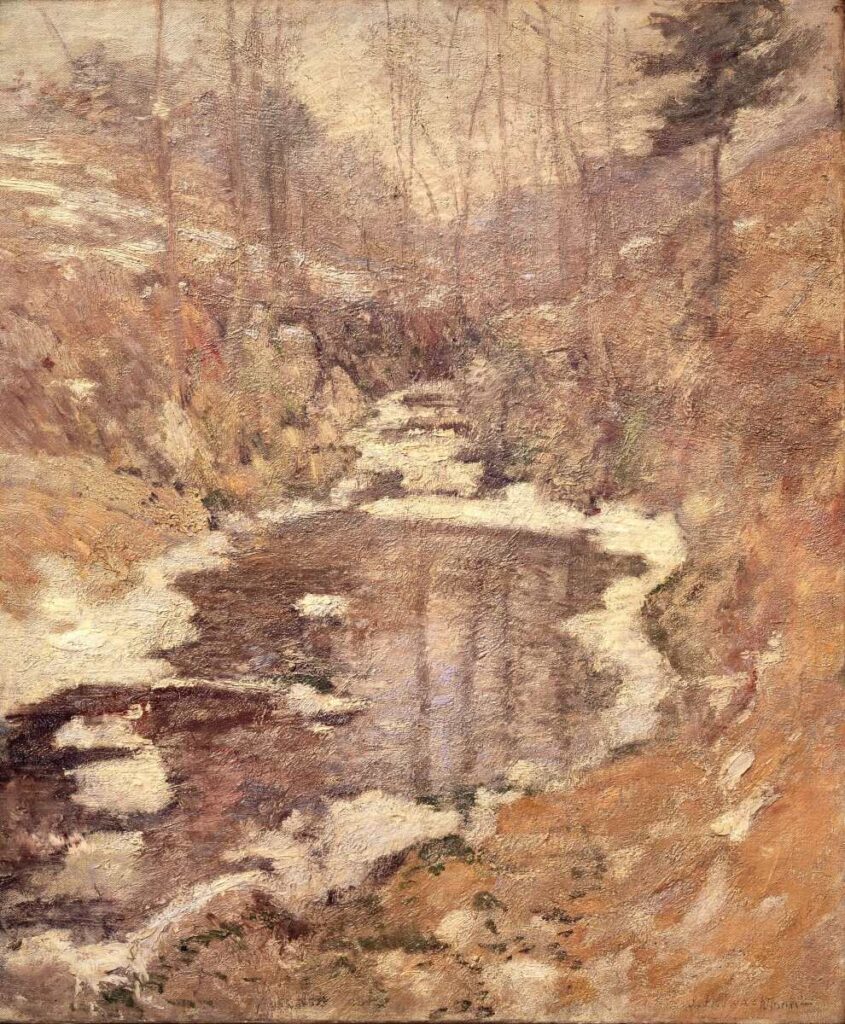

As to be expected, Twachtman’s artmaking evolved throughout his career. He left behind the dark tones and heavy brushwork associated with the Munich School and the more colorful, dashing mode he preferred when in Venice. By the 1890s, his French-influenced painting technique was lighter in stroke and palette with silvery-greens and whites dominating. While art critics and consumers did not always value Twachtman’s forward-looking style of the Greenwich years, many artists did.

The words “intimate,” “meditative” and “innovative” are often used to describe the paintings and sketches of the plein air painter and pastelist. He explored the realm of observation and sensation, capturing glimpses of domestic life, the built environment and naturally occurring features at varying times of day and year. Twachtman experimented with perspective, layout and subtle hues in his tightly cropped, impressionistic vignettes.

Peters pointed to “In the Garden” and “Hemlock Pool” as illustrative of Twachtman’s effects. Regarding the first painting, she observed “in the forward-tilted picture plane, where the path recedes on an upward diagonal, there is a feeling of the inevitability of moving toward the house… Everything has been plotted and controlled.” In the second, Peters remarked that initially the viewer “does not realize that the lines in the pool are shadows cast by the bare trees on the hillside so that what is above and against the sky is also in the earth and water…. It becomes less rather than more familiar, allowing us to merge with it because we’re not using logic to experience it.”

Twachtman died unexpectedly in Gloucester, Mass., at the age of 49. Thomas W. Dewing, also a member of The Ten, posthumously portrayed Twachtman as a “most modern spirit….too modern, probably, to be fully recognized or appreciated at present; but his place will be recognized in the future.”

Peters discussed the new ways art historians are looking at the Impressionist movement, including her own interest in eco-critical studies. She noted that Twachtman’s “work does not fit the characterization of American Impressionism as nostalgic. Unlike many other American artists who used Impressionist methods to heighten the beauty of American motifs, such as colonial churches, Twachtman related Impressionism to the subjectivity of perception and experience, exploring how things themselves only have meaning through how they are seen and understood… By depicting his home and land repeatedly from the same and different vantage points, he demonstrated that only in seeing a place in a multitude of ways – in its physical, emotive and conceptual aspects – can it be understood.”

The exhibition curator also situates Twachtman within an international context, highlighting the artistic impulses, style attributes and sources of inspiration he shared with the French Impressionist Claude Monet. Both saw their homes as places to be shaped and as worthy subject matter. They possessed a mutual friend in Theodore Robinson, an artist represented in the “Life and Art” exhibition. In addition, Twachtman and Monet were part of a four-person show mounted by New York’s American Art Galleries in 1893.

On November 15, Lisa Peters will speak about their commonalities in her lecture “Twachtman and Monet: Impressionist Crosscurrents in the 1890s.”

Peters has crafted a precise, nuanced exhibition of the late-period art produced by the enigmatic artist. Having studied Twachtman for more than 30 years, she is completely at ease explaining the poetical interchange between place and perception that dominated his Greenwich work. The result is a moving, contemplative experience not to be missed.

The companion catalog by Dr Lisa N. Peters is published by the Greenwich Historical Society.

“Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman” will be on view at the Greenwich Historical Society until January 22.