LIFE AND ART: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman

October 19, 2022 – January 22, 2023

The Cincinnati-born artist John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902) reached artistic maturity while living from 1890 to 1899 in Greenwich. Here he rendered paintings of his home and property that earned him the reputation as the most original of the leading American Impressionists.

From the beginning of his career, Twachtman was committed to creating landscape paintings in the realist tradition, drawing inspiration from his immediate observations during trips to Europe and at home in the United States. However, he struggled with the realization that the natural world did not provide the sense of completeness he believed to be essential in art. In Greenwich, Twachtman achieved this completeness by training his eye on a setting he shaped himself.

This exhibition takes a unique holistic approach to Twachtman’s Greenwich oeuvre, considering it in a unified context encompassing both the changes the artist made to his home and its surrounding landscape, and the images he derived from this subject matter. It reveals developments that occurred concurrently as Twachtman met his aims. At first he sought to establish a harmonious relationship between his home and the existing landscape; gradually he took more control of his environment, turning his home ground into a work of art in its own right. In the process he became less beholden to nature, imposing aesthetic control over his surroundings. Twachtman’s paintings parallel this progression, demonstrating how life and art came together, providing him with a sense of contentment and making his Greenwich art a form of autobiography.

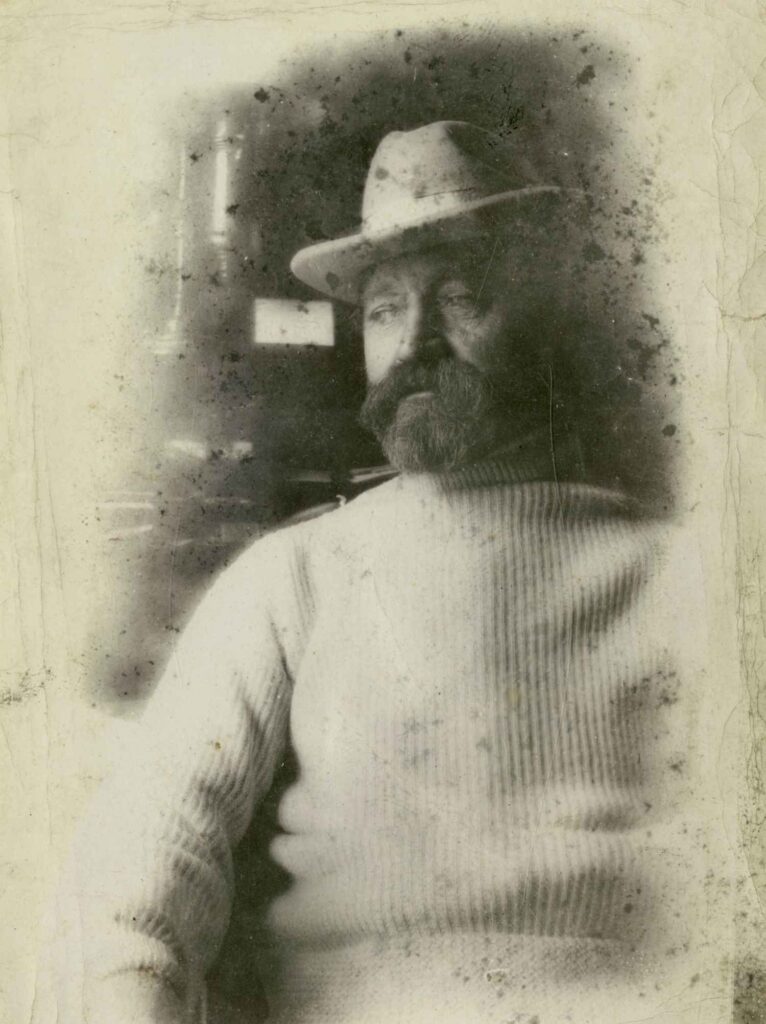

John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902)

Born on August 4, 1853, in Cincinnati, Ohio, to German immigrant parents, John Henry Twachtman received art instruction locally in his teens. Between 1875 and 1885, he traveled to Europe four times, studying in Munich and Paris, while also establishing his place in the New York art world. There he was a leading figure in a new generation of artists who broke from the idealized landscapes of the Hudson River School to cultivate subjective stylistic modes. In 1881 he married fellow Cincinnati artist Martha Scudder. He settled with his family in Greenwich in 1890, and five of his seven children survived to adulthood. In Greenwich, Twachtman eventually owned seventeen acres of land that, along with his home, were his primary subject matter for ten years. Due to financial constraints, he left his Greenwich home in 1899 (although it remained in the possession of the family). Subsequently he stayed at the Players Club in New York and the Holley House in Cos Cob (now the Bush-Holley House). He spent those summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where he died suddenly on August 8, 1902, four days after his forty-ninth birthday.

Due to his expressive Impressionist method and concentration on his immediate surroundings, Twachtman is often viewed as the closest U.S. artist to the French Impressionist Claude Monet. He was a member of the Ten American Painters, who held their own exhibitions beginning in 1898 in the manner of the French Impressionists. A “painter’s painter,” Twachtman was unsuccessful at marketing and selling his work, but he was revered by his peers for creating works that appeared ahead of their time. Indeed, in the early twentieth century, his paintings were avidly sought by museums and inspired modernist artists, including Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove and Milton Avery

Settling In

‘Hangroot,’ the scene of the artist’s home, has been brought out on the canvas, with its many cozy and inviting spots.

Greenwich Graphic, April 4, 1891

John Henry Twachtman

The Old Homestead, Greenwich, Connecticut, ca. 1890–91

Pastel on paper

Private collection

Probably shown in an 1891 solo exhibition at New York’s Wunderlich Gallery with the title House at Hang Root, this pastel is among Twachtman’s earliest depictions of his Greenwich home. His view is toward the house’s north (or rear) facade. In it one can discern two distinct parts: at the left is the original saltbox with its central chimney; at the right is the addition Twachtman constructed when he settled with his family in Greenwich in 1890. The north-facing dormer, visible in the new addition, was the location of Twachtman’s studio. Visible at the right is the contour of the root cellar, dug into the hillside, which had been pre-existing on the land. Here Twachtman stood back from the house as if to consider its compositional possibilities in relation to the natural world. Within a couple of years, he would harmonize it more into the land, bringing down its eaves and extending it in all directions.

Twachtman used pastel with delicacy and precision to render architectural form and implied details in the landscape and atmosphere. His pastel approach—demonstrating a sensitivity to the properties of his medium and his incorporation of the paper’s tone into his designs—was often related to that of James McNeill Whistler.

Theodore Robinson (1852–1896)

Twachtman’s House, 1892

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Twachtman did not date the artworks he made during his Greenwich years. It is therefore a stroke of luck that on a visit to Greenwich, his close friend Theodore Robinson created this painting—dated January 17, 1892—of the north facade of Twachtman’s home. As can be seen here, as well as in a photograph Robinson took at about the same time, there are three chimneys on the house. The chimney at the western end of the dwelling (seen here at the far right) was added after Twachtman’s initial renovations. He would later remove the central chimney on the original saltbox when he constructed a new kitchen and separate dining room.

Robinson rendered this painting during a visit to Greenwich, working on it quickly in the outdoors over the course of two days. In contrast to Twachtman’s images, where the house’s contours are softened, Robinson gave the structure a solid, fortress-like aspect, portraying it as a place of protection and security. Robinson, who never married, expressed his response to a place where he was embraced and given refuge by the Twachtman family. He wrote in his diary that this painting was one of his “best things.”

Theodore Robinson, Snow Scene with House, ca. 1892

Gelatin silver print, 5-1/2 × 9-1/4 inches

Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago; Gift of Ira Spanierman

Between 1887 and 1892, Theodore Robinson went back and forth between the US and Giverny, the Normandy town that was home to Claude Monet and a colony of Anglo-American artists. Robinson was one of the foreigners in Giverny who became closest to Monet. His diary is filled with reports of visits with Monet, and he and Monet corresponded when he was in the US, where he spent much time in Greenwich. On March 22, 1892, he referenced Twachtman’s home in a letter he sent from New York to Monet:

. . . I escape to the countryside at a painter friend’s home—an hour by train from the city. It is a property well arranged, with pretty motifs everywhere, [that he can paint] without leaving his place. It is an interesting region—woods everywhere and especially many rocks everywhere, from which fences are made—and there are many. When it snows, it is charming—even though it is much colder than in Giverny and there is almost always blinding sunshine. Nevertheless, I have seen pretty things. I even worked a little. . . .

John Henry Twachtman

Snowbound, ca. 1892–93

Oil on canvas

Montclair Art Museum, New Jersey; Museum purchase, Lang Acquisition Fund

Twachtman made a number of modifications to his home by January 1892 to blend it into its surroundings. He lowered the eaves and, on the east end of its north facade, he built a porch enclosed by chest-high stone walls. He also installed a new central door with a small temple-front gable above it that led into an elegant vestibule. By the time he painted Snowbound, he had eliminated the original saltbox’s middle chimney, which was still present when Robinson painted the house from a similar vantage point.

In Snowbound, Twachtman captured his home as a self-contained shape, bookended by its two remaining rust-red chimneys. Locked in by the frozen ground cover, the dwelling appears a cozy and stoic refuge. The similarly snow-covered birdhouse in the upper right adds to the work’s theme of shelter from the harshness of the elements. The painting can be related to John Greenleaf Whittier’s 1866 poem, “Snow-Bound,” in which a heavy winter’s snow provides an occasion for a family to gather and tell stories.

John Henry Twachtman

The Artist’s House, ca. 1892–95

Pen and ink on paper

Private collection

Speaking to his students in 1899, Twachtman said of drawing in pen and ink: “Think less of the way you are making the lines, more of giving a true impression of nature.” He followed such an approach here, depicting the familiar features of his home ground in a design in which the exposed paper reveals the role of snow as a unifier. The elongated horizontality and medium of this drawing evoke the format of traditional Chinese handscrolls that were often accompanied by poems, reflective of the Chinese tradition of contemplation through landscape art. Twachtman underscored this association by adding a large calligraphic signature on the lower left, suggestive of the Chinese esteem for the beauty of writing.

Achieving Harmony

I can see how necessary it is to live always in the country – at all seasons of the year.

John Henry Twachtman to Julian Alden Weir, December 6, 1891

John Henry Twachtman

From the Upper Terrace, ca. 1892–93

Oil on canvas

Private collection

In this bird’s-eye view, Twachtman captured his self-created, self-contained world in Greenwich. Crowned by trees, his redesigned house is the point from which all aspects of the scene emanate, including the serpentine lines of paths and Round Hill Road at the left. The cultivated garden behind the house spreads outward, blending into nature, conveying the accord between it and its surroundings. A corner of the artist’s barn in the lower left seems a surrogate for the artist, looking up at the house in admiration.

Throughout the work Twachtman used the broken daubs of paint typical of Impressionism, while capturing the familiar attributes of his property, including the birdhouse at the work’s center and the well house shielded by bushes at the side of the road. This painting was probably among those in an 1893 four-artist exhibition that critics related to a painting by Claude Monet of his home in Vétheuil, France. One remarked that Twachtman had taken a hint from Monet in his “preference for commonplace subjects made beautiful by light” in an image of a home that appeared more “picturesquely situated” than Monet’s.

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926), The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil, 1881

Oil on canvas, 39-3/8 × 31-1/2 inches

Private collection

John Henry Twachtman

Hollyhocks, ca. 1892–93

Oil on canvas

Collection of David B. Findlay Jr. Family

In Hollyhocks, instead of simply depicting his home, Twachtman used the structure as a means of exploring formal considerations. Here, he was interested in the way that the verticality of the blooming hollyhocks, seen close up from their position on a hill to the north of his home, balanced the horizontal shape of the house’s roofline. The grass-covered root cellar that was located to the north of the house is depicted as a strong block of green earth

immediately beyond the pink floral stems, serving as a means of uniting flowers and architecture compositionally. Associating his home with flowers, Twachtman suggested that both were forms of beauty to be enjoyed aesthetically.

John Henry Twachtman

Barn in Winter, Greenwich, Connecticut, ca. 1890–91

Oil on canvas

Private collection, Delaware, Courtesy of Art Finance Partners LLC

To paint snow scenes in Greenwich, Twachtman mounted an old milk wagon on a sledge, heated by an oil stove. However, he also rendered winter views from the window of his studio on the second floor of his home, looking north to the square-shaped family barn, represented at the center of this work. The white ground cover provided him with a means of seeing the landscape in new ways, and here at the left he used the blanket of white snow to visually unite the roof of the root cellar in the foreground with the far hill to its north.

In this scene Twachtman expressed the blending of the human and natural into a totality that gave him a sense of completeness. He treated the barn as a soft-edged, reflective shape that blended into the atmosphere, with footsteps leading through the snow as a curvilinear pattern. At the right he allowed lines of bare canvas to show through amid the thick impasto he used for the snow to indicate passing carriage tracks, which reveal the presence of Round Hill Road. He saw the landscape from an ecological standpoint, capturing ways that human activity interacted with and gave life to the natural environment. He was the preeminent painter of snow among the noted US Impressionists, recording the colors in its surface and bringing out its varied textures with vital experimental paint handling.

John Henry Twachtman

Barnyard, ca. 1896–97

Oil on canvas

Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Connecticut; Gift of the Fine Arts Collection of The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company

At the time of his 1901 exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, Twachtman told a reporter: “The scenes on my farm at Greenwich, Conn., are perhaps my favorites . . . one of these painted by my son, J. Alden Twachtman, and myself—the one representing a little child feeding chickens—is an especial favorite of mine.”

Featuring as its subject the family’s chicken coop—probably constructed in the late 1890s—in this painting Twachtman addressed the age-old theme of mother and child, depicting his wife Martha standing back to allow her young daughter, Violet, to take on the responsibility of caring for the chickens by herself. He portrayed doves fluttering down and alighting as if to bless the scene. Despite his characterization of his home, it was not a working farm, but a suburban place for the enjoyment of nature’s beauty. As Susan G. Larkin has noted, in the work Twachtman “drew on a body of conventions in European art to give a rustic image of family life an aura of benediction.”

John Henry Twachtman

September Sunshine, ca. 1892–94

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

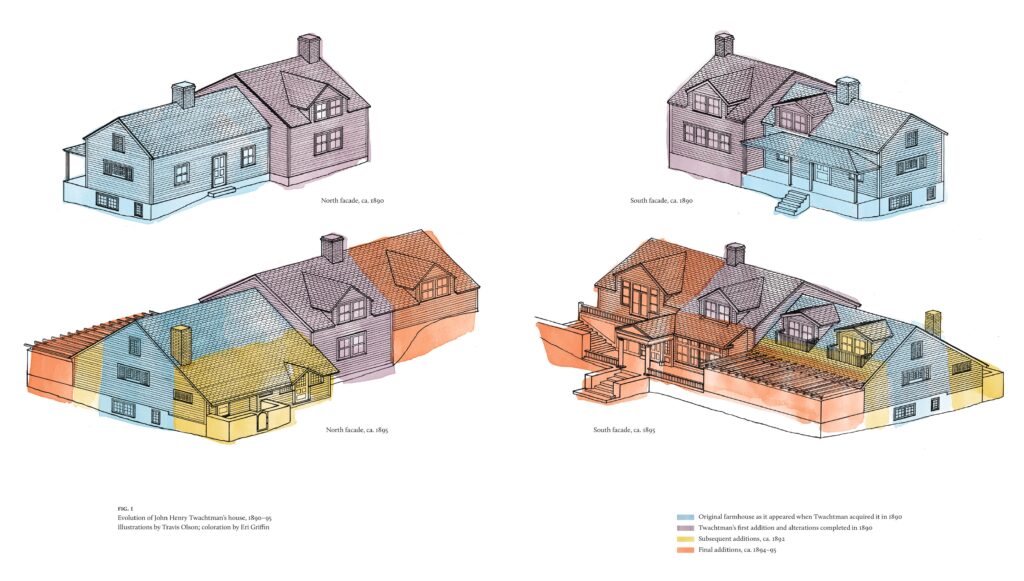

Twachtman’s artworks depicting his Greenwich home provide a record of the expansions and extensions he made to the structure over the years. Upon acquiring the property in 1890, he built a significant westward addition to the original farmhouse. Just a few years later he made further modifications to the southern facade, adding decorative balustrades to the dormers and enclosing the porch to create a veranda, which served the family as an outdoor dining hall. A graceful awning over the veranda provided shade.

In September Sunshine, a view of the south facade from an oblique northwest angle, Twachtman cropped the scene to frame the house on a gentle curve in glowing sunlight. With autumnal trees arching over it, he made it into a shimmering shape, revealing that the dwelling was meant to be appreciated aesthetically—as a work of art. In the mid-1890s, he added a further westward addition in which a Tuscan-style portico served as a new formal entryway.

A Place in the Natural World

Seventeen acres were chosen full of motives for a painter – the land dips and curves in a thoroughly natural way.

Alfred Goodwin, Country Life in America, October 1905

Horseneck Brook and Hemlock Pool

In his paintings Twachtman depicted his home in relation to the land, but he also portrayed aspects of his property to which he contributed in both overt and subtle ways. Through intimate vantage points, he situated himself in his scenes, conveying the immediacy of his responses to the Hemlock Pool, a calm, rock-edged body of water located to the west of his home. He created images of the Japanese-inspired bridges crossing over Horseneck Brook that he built seasonally to add a sense of artistic refinement to the landscape. He returned repeatedly to Horseneck Falls, the steepest cascade on the brook, producing close-ups of the water falling over rocks in images that are almost fully abstract. His paintings make it seem possible for the viewer to enter into them and see this countryside through his eyes. He preserved his Greenwich experience in his art for posterity.

Horseneck Falls, photographed in the 1880s Greenwich Historical Society

John Henry Twachtman

Hemlock Pool, ca. 1895–99

Oil on canvas

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts; Gift of anonymous donor

One of Twachtman’s favorite subjects was the Hemlock Pool, formed on Horseneck Brook where it widened, due west of his home. He owned property on both sides of the brook after 1891 and expressed his sense of belonging to the land in the harmonious form of the pool, arranged broadly in this composition. Here he organized its shape in relation to his upright vertical canvas, where it recedes more deeply into the distance than in other images of the subject. The intimate viewpoint implies the artist’s presence in the scene and draws the viewer into close rapport with its quietude and the vitality of the Art-Nouveau-like curvilinear rim of snow that has yet to melt. The painting is among many by Twachtman that demand sustained attention, gradually revealing their subtleties and thus eliciting meditation on the part of the viewer.

John Henry Twachtman

Bridge in the Woods, ca. 1896–99

Oil on canvas

Private collection

In the late 1890s Twachtman built a successive series of footbridges over Horseneck Brook, drawing inspiration from the bridges found in Japanese prints and Chinese ink-wash paintings. The version of the bridge portrayed here—which is also the subject of a painting now in the collection of the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester, New York—is similar to the low span in the latter. The work’s low angle from the near shore invites the viewer to cross it. The delicate latticework and canopy indicate that Twachtman also considered the bridge an aesthetic form in its own right and painted it white so that it gleamed in the sunlight. The painting appears a quickly rendered plein-air work, but the vertical emphasis of the design is, nonetheless, skillfully matched to the canvas shape.

At the time Twachtman was creating and painting his white bridges, he was unaware of the Japanese footbridge built by the French artist Claude Monet in the water garden he created at his home in the French village of Giverny. Monet produced a series of paintings of his bridge in 1899, which were not seen in America until 1901. Twachtman’s and Monet’s bridge paintings are different but share the idea of a bridge as a means of enhancing the visual pleasure of a natural setting.

Robert Reid (1862–1929)

Spring Landscape, ca. 1896–99

Oil on canvas

Private collection

In 1895 the Art Amateur reported: “Mr. Twachtman’s country place seems to be a regular rendezvous for Impressionists.” The article noted that among those to frequent it was the artist’s friend, Robert Reid, who added “his testimony to its attractions.” In this instance Reid depicted Horseneck Brook with Twachtman’s white bridge at its center, glistening on a sunlit spring day. While uniting the arrangement, the bridge also adds a genteel and civilizing note to the overgrown landscape. Creating a balanced design, Reid conveyed a feeling of refinement and repose in the work, qualities considered a counterforce to the stress and ugliness of modern city life over which industrialization was gaining increasing control.

John Henry Twachtman

Waterfall, Blue Brook, late 1890s

Oil on canvas

Cincinnati Art Museum; Annual Membership Fund Purchase

Twachtman painted Horseneck Falls, the largest cascade on Horseneck Brook, several times throughout the years he lived in Greenwich. In the late 1890s he created a small group of images of the subject, in which he limited the depth of field and set his horizon lines high, bringing the enlarged forms of water and rocks close to the picture plane. These works exemplify his interest in seriality, which implies that a subject consists not of a solitary entity but of the multiple ways it is experienced.

Using this restrictive framing, Twachtman referenced a waterfall’s incongruity as in motion and fixed at the same time. As such, his late waterfall paintings are a summary of what his Greenwich life represented for him: vitality and stability, change and timelessness. This was Twachtman’s only painting to enter a public collection in his lifetime, when it was purchased by the Cincinnati Art Museum from an exhibition held there in 1900 of his work and that of his son, Alden.

The Merging of Home and Art

The great beauty of design, which is conspicuous in Twachtman’s paintings, is what impressed me always.

Childe Hassam, North American Review, April 1903

John Henry Twachtman

In the Garden, ca. 1895–99

Oil on canvas

Private collection

In the late 1890s, Twachtman turned from the more detached, self-reflective views of his home that he had rendered earlier, expressing in more intimate and abruptly cropped images how he had shaped the land and become a creator of nature itself. He portrayed his home and garden in new inventive, abstractly conceived designs. Here he limited his angle to include only the east corner of the north facade of his home, using the sunlit path and the columns on the back porch to establish a geometric arrangement fitting the work’s vertical format. The path’s processional movement and the altar-like arrangement of stairs, where potted plants reach up toward the columns on the stone walls on the back porch, suggest the artist’s reverence for the beauty of his home and its inner life. The painting exemplifies the greater control over the natural landscape that Twachtman exerted toward the end of his Greenwich years as he turned his home ground into a work of art.

John Henry Twachtman

In the Greenhouse, 1895–99

Oil on canvas

North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh; Purchased with funds from the State of North Carolina

As is typical for Twachtman—who often did not formally title his work—the title of this painting is not original. As such, the reference to a greenhouse is misleading; the white rectangle visible in the upper register actually depicts the roof of the barn to the rear of the artist’s house (also visible in Barn in Winter). However, the title is to some degree apt in its reference to the notion of cultivation in progress. In the foreground are a rustic barrel and potted plants. Although the flowers are not part of a formal garden, they are arranged in groups by color, implying the tending and planning of the garden plot by the artist. The barn’s roof serves as a frame for the design, further indicating that Twachtman saw his garden as an aesthetic totality that he had created himself.

John Henry Twachtman

Pink Flowers, ca. 1895–99

Oil on canvas

Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida; Gift of Elsie and Marvin Dekelboum

In this painting’s low angle and close-up view of garden flats, where potted semi-double peonies are probably soon to be planted in the ground, Twachtman implies his role as the one tending to the flowers. The painting departs from traditional floral still lifes, not only in its outdoor setting but also in the suggestion of the artist’s presence in the scene. The solidity of the buildings in the background—probably representing the barn and outbuildings—counterbalances the energy of the sunlit blossoms, while establishing the domestic setting.

John Alden Twachtman and John Henry Twachtman

Greenwich Garden, ca. 1895–99

Oil on canvas

Private collection

This painting is signed by the artist’s son, Alden (who was born in 1882 and began studies at the Yale University School of Fine Arts in 1897), but stylistically it is characteristic of John Henry Twachtman, suggesting that the elder artist wanted his son to feel part of the creative process, even if his participation was minimal. In a square composition, Twachtman integrated a section of the house’s north facade with the garden flowers that radiate across the picture plane. The innovative arrangement demonstrates Twachtman’s modernity, which was noted throughout his career by his fellow artists, who continually pronounced him to be ahead of his time. Concurrently, the collaborative aspect and composition express the way that life and art intermingled for Twachtman in Greenwich. As noted in an article in 1940 in the Bridgeport Sunday Post, the artist’s five children “gathered about him in true family spirit.”

John Henry Twachtman

The Cabbage Patch, ca. 1895–99

Oil on canvas

Private collection

In The Cabbage Patch, Twachtman expressed his immersion with his Greenwich environment after his final renovations to his home undertaken in the mid-1890s. Standing amidst his garden, he brought out its abundance with energetic Impressionist brushwork, while depicting the house’s north facade as a delicate armature in harmony with the garden’s flowers. In the right distance, potted plants resting on the ledges of a small staircase (featured from closer range in the painting In the Garden) direct our gaze to the small gable over the back door, toward which the foliage and flowers rise up.

An Artist's House

Unearthing the Story of a House

A team of art historians and scholars worked with the current owner of Twachtman’s home, John Nelson, and architectural historian James Sexton, Ph.D., to create a detailed chronology of Twachtman’s changes to the dwelling. This close examination of the house itself, along with a careful study of Twachtman’s works (which he did not date after 1883) and consultation of historical sources, made this exhibition possible. The diagram above reveals results of the team’s findings. The artworks displayed in the exhibition provide an opportunity not only to see the way the dwelling evolved—look for the changing number of chimneys on the home—but also to enter into Twachtman’s world, as he reconciled the needs of his family with his desire to match his artistic ideals to the reality of his environment as a means of achieving contentment.

Letter from John Henry Twachtman to Stanford White, February 26, 1890

Stanford White Papers, Collection of the New-York Historical Society

In February 1890, only six days after finalizing the purchase of his Greenwich house, Twachtman wrote a letter to his friend, the architect Stanford White, seeking advice about an addition he planned to make to the small existing structure. In his letter, discovered in the course of organizing this exhibition, Twachtman made a sketch of the house’s south front to convey his intended building plans. The letter clarified many aspects of Twachtman’s initial decisions in the redesign of his home.

South facade of Twachtman’s Greenwich house, showing later addition and portico

Published in the magazine article “An Artist’s Unspoiled Country Home” by Alfred Goodwin in Country Life in America, October 1905

In 1894 Twachtman made further alterations to the house, building another western addition for a new bedroom suite. He built it on top of rocks so that its ground level was on the dwelling’s second floor. He also extended it to the south, including creating a veranda on the east porch. Evoking a Parisian open-air café, it was used as an outdoor dining room for the artist’s family and friends. Perhaps most notably, Twachtman constructed a neoclassical portico with Tuscan columns to frame and give elegance to the house’s new front door.

John Henry Twachtman, My House, ca. 1896–99

Oil on canvas, 30 × 20-7/8 inches

Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of the Artist

Twachtman depicted the classically inspired portico on the south front of his home in the painting My House.

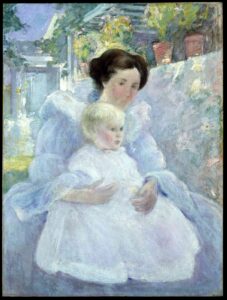

Twachtman Family Photographs from the Greenwich Historical Society Collection

A large painting visible in the upper-right corner of this photograph of the Twachtman family living room―and reproduced at right―depicts the artist’s wife Martha and the couple’s daughter Violet. In the Twachtman home, the painting was embedded directly into a niche in the living room wall, recalling a Medieval or Renaissance icon.

John Henry Twachtman

Mother and Child, ca. 1897

Oil on canvas

45 ½ x 36 inches

Collection of Sharon P. and John D. Rockefeller IV

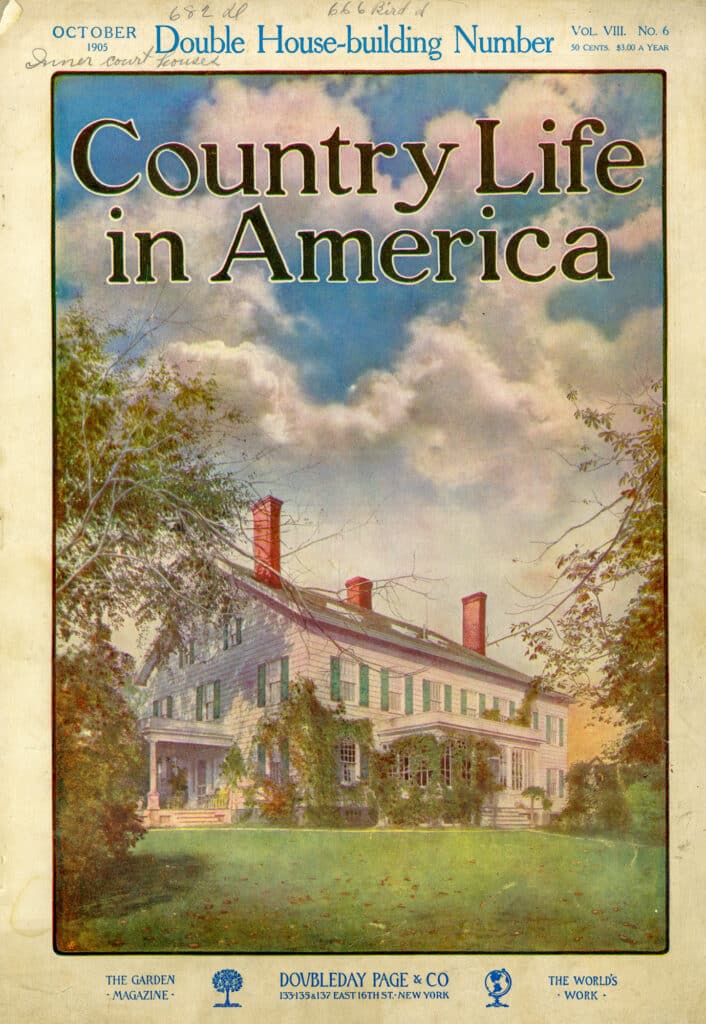

6. Magazine article: “An Artist’s Unspoiled Country Home,” Country Life in America, October 1905. Greenwich Historical Society

Three years after Twachtman’s death, his Greenwich house and its surroundings, including his garden, were featured in a photo essay published in the popular home and garden magazine Country Life in America. Writer Alfred Goodwin praised the home’s artistic setting within the rural hilly landscape, observing that “[t]he whole place has co-operated with Nature.” The photographs were taken by the pictorialist photographer Henry Troth.

You can read the entirety of Alfred Goodwin’s article about Twachtman’s home in Greenwich by following the link below.

Exhibition Credits

Life and Art is generously supported by the Henry Luce Foundation for American Art and First Republic Bank. Its catalogue is made possible by a grant from the Wyeth Foundation for American Art.

The architectural study of the John Henry Twachtman house was made possible by the Jane Henson Foundation, Charles Hilton Architects, and John Nelson.

Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman was curated by Lisa N. Peters, Ph.D.

Exhibition Consultant: Susan G. Larkin, Ph.D.

Exhibition Design: Johanna Goldfeld, Exhibitista Creative

Art Handling and Installation: Level Fine Art Services, Francisco & Francisco Painters, R&L Home Services

Exhibition Catalogue: Jenny Chan, Jack Design; Printed by Puritan Capital

Marketing and PR: Laura McCormick, McCormick PR Group

Life and Art: The Greenwich Paintings of John Henry Twachtman Honorary Committee:

Davidde & Ronald Strackbein

Cross Family Charitable Fund

John Nelson

David Brownwood

Tom & Connie Clephane

Alexandra & Peter Cummiskey

Carolyn & Maurice Cunniffe

John & Patricia Klingenstein

Susan G. Larkin

Isabel & Peter Malkin

Dave & Susan Ormsby

Lucy & Larry Ricciardi

Charles & Deborah Royce

Dave & Reba Williams

Organized for the Greenwich Historical Society by Maggie Dimock, Curator of Exhibitions and Collections. Research and exhibition support provided by Kelsie Dalton, Assistant Curator for Interpretation and Collections, Christopher Shields, Curator of Library and Archives and Dean McKenna, Curatorial Assistant/Project Digitization Associate.

Additional support provided by Greenwich Historical Society staff including Ashley Aberg, Stephanie Barnett, John Bridge, Michele Couture, Barbara Johann, Laura Kelly, Stephanie Lally, Heather Lodge, Dianne Niklaus, Ryan Nuckel, Kathy Stefanatos, Daniel Suozzo, Alexis Zuniga and Debra Mecky.

Additional thanks to Theresa Andre, Karen Frederick, Anna Greco, Jingwei Li, Cai Pandolfino and Mary Vinton.