The second in a series of essays featured in conjunction with Greenwich Faces the Great War.

By Kathleen Eagen Johnson

The experiences of individual women and girls in Greenwich illustrate the political ramifications of both extraordinary and commonplace activities during World War I. Many women took on jobs traditionally filled by men, running their husbands’ businesses and working as military drivers/auto mechanics, farmers and waiters. Jutta J. Anderson, Florence L. Dixon and seven other women from Greenwich served as nurses in the U.S. Army.

Grace Gallatin Seton numbered among the Greenwich women who received accolades for their wartime service and recognized how such work supported the suffragette cause. Seton, whose husband was the famous nature writer Ernest Thompson Seton, founded Le Bien-Être du Blessé (Welfare of the Injured) Women’s Motor Unit in 1916. This all-female transport service moved people and goods in the war zone. She was a leader of the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association during the 1910s.

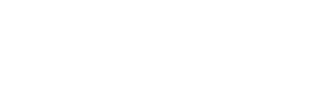

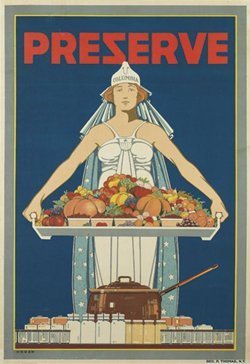

Others in Greenwich’s suffrage movement turned their attention to maximizing agricultural and food production. Rosemary Hall headmistress Caroline Ruutz-Rees, who led the Connecticut Division of the Woman’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, and philanthropist, feminist and renowned art collector Louisine Havemeyer publicly championed the Woman’s Land Army of America. The WLA was modeled on the British Women’s Land Army. In both programs, women took the place of men who left farm fields to fight on battlefields. Havemeyer founded the Greenwich Canning Kitchen, a model program for preserving home-garden bounty. Havemeyer had co-founded the National Women’s Party with Alice Paul in 1913. She provided financial support to—and spoke, marched and demonstrated for— the cause of women’s suffrage. Ruutz-Rees served on the executive board of the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, was active in the Greenwich Equal Franchise League and organized the National Junior Suffrage Corps. Her students cultivated potato fields and war gardens while also helping with landscape maintenance on the school’s campus.

The Woman’s Land Army was one of the many war-related initiatives that helped break down gender barriers as women assumed the heavy farm labor typically reserved for men. With a training camp in nearby Bedford, New York, the WLA began working in farm fields in Greenwich, such as Sabine Farms. The Greenwich Canning Kitchen was established in 1917 as a way to contribute to food coffers. The goal was to preserve the produce of war gardens and small farms that might otherwise go to waste. Residents brought in produce to be processed for their own use or for consumption by troops or civilians in need. This program operated out of a storefront on Railroad Avenue.

As was true of women across the nation, Greenwich women and girls immersed themselves in American Red Cross activities. Louise Van Dyke Brown, Alexandra Spann and others recalled (as part of the Greenwich Library Oral History Project) gathering at the Greenwich YMCA and other locations to fashion surgical dressings and to knit socks, mufflers, helmet liners and other items for soldiers. Annie Louise Brush wrote of this work in her diaries, which were recently added to the collection of the Greenwich Historical Society. On April 21, 1918, she recorded that the death of Colonel Raynal Bolling from Greenwich had been verified and that “Mrs. Bolling is from all I hear a herione [sic], when she knew that her husband was missing she controlled herself and had the people come to her house as usual for dressings and worked with them.”

Both far from and near to home, Greenwich women supported the war effort in meaningful ways. They served as nurses, drivers, farmers and Red Cross workers, assuming jobs generally reserved for males in response to a labor shortage. While anti-suffragettes and suffragettes alike took part in food and fuel conservation, fundraising for relief charities and other activities, there was a definite spirit in the air that women had shown their mettle and were deserving of the vote. This was particularly strong in Greenwich, the home of some of the movement’s most high-profile leaders. Women’s passionate service during the war inspired the previously reluctant President Wilson to finally agree to women’s suffrage. As he recognized in a speech to Congress in 1918, “We have made partners of the women in this war; shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

The expanded version of this article will be published in the Winter 2014/15 issue of Connecticut Explored magazine and on the Historical Society’s website. Kathleen Eagen Johnson is the guest curator of Greenwich Faces the Great War. She is a freelance museum consultant and writer at HistoryConsulting.com.

Col. J. Alden Twachtman: Artist as Soldier >